Evelyn Underhill (6 December 1875 – 15 June 1941) was an English Anglo-Catholic writer and pacifist known for her numerous works on religion and spiritual practice, in particular Christian mysticism.

In the English-speaking world, she was one of the most widely read writers on such matters in the first half of the 20th century. No other book of its type matched that[clarification needed] of her best-known work, Mysticism, published in 1911.[1][2]

Underhill was born in Wolverhampton. She was a poet and novelist as well as a pacifist and mystic. An only child, she described her early mystical insights as "abrupt experiences of the peaceful, undifferentiated plane of reality—like the 'still desert' of the mystic—in which there was no multiplicity nor need of explanation".[3] The meaning of these experiences became a lifelong quest and a source of private angst, provoking her to research and write.

Both her father and her husband were writers (on the law), London barristers, and yachtsmen. She and her husband, Hubert Stuart Moore, grew up together and were married on 3 July 1907. The couple had no children. She travelled regularly within Europe, primarily Switzerland, France and Italy, where she pursued her interests in art and Catholicism, visiting numerous churches and monasteries. Neither her husband (a Protestant) nor her parents shared her interest in spiritual matters.

Underhill was called simply "Mrs Moore" by many of her friends. She was a prolific author and published over 30 books either under her maiden name, Underhill, or under the pseudonym "John Cordelier", as was the case for the 1912 book The Spiral Way. Initially an agnostic, she gradually began to acquire an interest in Neoplatonism and from there was increasingly drawn to Catholicism against the objections of her husband, eventually becoming a prominent Anglo-Catholic. Her spiritual mentor from 1921 to 1924 was Baron Friedrich von Hügel, who was appreciative of her writing yet concerned with her focus on mysticism and who encouraged her to adopt a much more Christocentric view as opposed to the theistic and intellectual one she had previously held. She described him as "the most wonderful personality. ... so saintly, truthful, sane and tolerant" (Cropper, p. 44) and was influenced by him toward more charitable and down-to-earth activities. After his death in 1925, her writings became more focused on the Holy Spirit and she became prominent in the Anglican Church as a lay leader of spiritual retreats, a spiritual director for hundreds of individuals, guest speaker, radio lecturer and proponent of contemplative prayer.

Underhill came of age in the Edwardian era, at the turn of the 20th century and, like most of her contemporaries, had a decided romantic bent. The enormous excitement in those days was mysteriously compounded of the psychic, the psychological, the occult, the mystical, the medieval, the advance of science, the apotheosis of art, the rediscovery of the feminine, the unashamedly sensuous, and the most ethereally "spiritual" (Armstrong, p. xiii–xiv). Anglicanism seemed to her out-of-key with this, her world. She sought the centre of life as she and many of her generation conceived it, not in the state religion, but in experience and the heart. This age of "the soul" was one of those periods when a sudden easing of social taboos brings on a great sense of personal emancipation and desire for an El Dorado despised by an older, more morose and insensitive generation.[2]

As an only child, she was devoted to her parents and, later, to her husband. She was fully engaged in the life of a barrister's daughter and wife, including the entertainment and charitable work that entailed, and pursued a daily regimen that included writing, research, worship, prayer and meditation. It was a fundamental axiom of hers that all of life was sacred, as that was what "incarnation" was about.

She was a cousin of Francis Underhill, Bishop of Bath and Wells.

Underhill was educated at home, except for three years at a private school in Folkestone, and subsequently read history and botany at King's College London. An honorary Doctorate of Divinity was conferred on her by Aberdeen University and she was made a fellow of King's College. She was the first woman to lecture to the clergy in the Church of England and the first woman officially to conduct spiritual retreats for the Church. She was also the first woman to establish ecumenical links between churches and one of the first woman theologians to lecture in English colleges and universities, which she did frequently. Underhill was an award-winning bookbinder, studying with the most renowned masters of the time. She was schooled in the classics, well read in Western spirituality, well informed (in addition to theology) in the philosophy, psychology, and physics of her day, and was a writer and reviewer for The Spectator.

Blue plaque, 50 Campden Hill Square, London Before undertaking many of her better-known expository works on mysticism, she first published a small book of satirical poems on legal dilemmas, The Bar-Lamb's Ballad Book, which received a favourable welcome. Underhill then wrote three unconventional, though profoundly spiritual novels. Like Charles Williams and later, Susan Howatch, Underhill uses her narratives to explore the sacramental intersection of the physical with the spiritual. She then uses that sacramental framework effectively to illustrate the unfolding of a human drama. Her novels are entitled The Grey World (1904), The Lost Word (1907), and The Column of Dust (1909). In her first novel, The Grey World, described by one reviewer as an extremely interesting psychological study, the hero's mystical journey begins with death, and then moves through reincarnation, beyond the grey world, and into the choice of a simple life devoted to beauty, reflecting Underhill's own serious perspective as a young woman.

It seems so much easier in these days to live morally than to live beautifully. Lots of us manage to exist for years without ever sinning against society, but we sin against loveliness every hour of the day.[4]

The Lost Word and The Column of Dust are also concerned with the problem of living in two worlds and reflect the writer's own spiritual challenges. In the 1909 novel, her heroine encounters a rift in the solid stuff of her universe:

She had seen, abruptly, the insecurity of those defences which protect our illusions and ward off the horrors of truth. She had found a little hole in the wall of appearances; and peeping through, had caught a glimpse of that seething pot of spiritual forces whence, now and then, a bubble rises to the surface of things.[5]

Underhill's novels suggest that perhaps for the mystic, two worlds may be better than one. For her, mystical experience seems inseparable from some kind of enhancement of consciousness or expansion of perceptual and aesthetic horizons—to see things as they are, in their meanness and insignificance when viewed in opposition to the divine reality, but in their luminosity and grandeur when seen bathed in divine radiance. But at this stage the mystic's mind is subject to fear and insecurity, its powers undeveloped. The first novel takes us only to this point. Further stages demand suffering, because mysticism is more than merely vision or cultivating a latent potentiality of the soul in cosy isolation. According to Underhill's view, the subsequent pain and tension, and final loss of the private painful ego-centered life for the sake of regaining one's true self, has little to do with the first beatific vision. Her two later novels are built on the ideal of total self-surrender even to the apparent sacrifice of the vision itself, as necessary for the fullest possible integration of human life. This was for her the equivalent of working out within, the metaphorical intent of the life story of Jesus. One is reunited with the original vision—no longer as mere spectator but as part of it. This dimension of self-loss and resurrection is worked out in The Lost Word, but there is some doubt as to its general inevitability. In The Column of Dust, the heroine's physical death reinforces dramatically the mystical death to which she has already surrendered. Two lives are better than one but only on the condition that a process of painful re-integration intervenes to re-establish unity between Self and Reality.[2]

All her characters derive their interest from the theological meaning and value which they represent, and it is her ingenious handling of so much difficult symbolic material that makes her work psychologically interesting as a forerunner of such 20th-century writers as Susan Howatch, whose successful novels also embody the psychological value of religious metaphor and the traditions of Christian mysticism. Her first novel received critical acclaim, but her last was generally derided. However, her novels give remarkable insight into what we may assume was her decision to avoid what St. Augustine described as the temptation of fuga in solitudinem ("the flight into solitude"), but instead acquiescing to a loving, positive acceptance of this world. Not looking back, by this time she was already working on her magnum opus.

Underhill's greatest book, Mysticism: A Study of the Nature and Development of Man's Spiritual Consciousness, was published in 1911, and is distinguished by the very qualities which make it ill-suited as a straightforward textbook. The spirit of the book is romantic, engaged, and theoretical rather than historical or scientific. Underhill has little use for theoretical explanations and the traditional religious experience, formal classifications or analysis. She dismisses William James's pioneering study, The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902), and his "four marks of the mystic state" (ineffability, noetic quality, transience, and passivity). James had admitted that his own constitution shut him off almost entirely from the enjoyment of mystical states, thus his treatment was purely objective. Underhill substituted (1) mysticism is practical, not theoretical, (2) mysticism is an entirely spiritual activity, (3) the business and method of mysticism is love, and (4) mysticism entails a definite psychological experience. Her insistence on the psychological approach was that it was the glamorous science of the pre-war period, offering the potential key to the secrets of human advances in intelligence, creativity, and genius, and already psychological findings were being applied in theology (i.e., William Sanday's Christologies Ancient and Modern).[2]

She divided her subject into two parts: the first, an introduction, and the second, a detailed study of the nature and development of human consciousness. In the first section, in order to free the subject of mysticism from confusion and misapprehension, she approached it from the point of view of the psychologist, the symbolist and the theologian. To separate mysticism from its most dubious connection, she included a chapter on mysticism and magic. At the time, and still today, mysticism is associated with the occult, magic, secret rites, and fanaticism, while she knew the mystics throughout history to be the world's spiritual pioneers.

She divided her map of "the way" into five stages: the first was the "Awakening of Self". She quotes Henry Suso (disciple of Meister Eckhart):

That which the Servitor saw had no form neither any manner of being; yet he had of it a joy such as he might have known in the seeing of shapes and substances of all joyful things. His heart was hungry, yet satisfied, his soul was full of contentment and joy: his prayers and his hopes were fulfilled. (Cropper p. 46)

Underhill tells how Suso's description of how the abstract truth (related to each soul's true nature and purpose), once remembered, contains the power of fulfilment became the starting point of her own path. The second stage she presents as psychological "Purgation of Self", quoting the Theologia Germanica (14th century, anonymous) regarding the transcendence of ego (Underhill's "little self"):

We must cast all things from us and strip ourselves of them and refrain from claiming anything for our own.

The third stage she titles "Illumination" and quotes William Law:

Everything in ...nature, is descended out that which is eternal, and stands as a. ..visible outbirth of it, so when we know how to separate out the grossness, death, and darkness. ..from it, we find. ..it in its eternal state.

The fourth stage she describes as the "Dark Night of the Soul" (which her correspondence leads us to believe she struggled with throughout her life) wherein one is deprived of all that has been valuable to the lower self, and quoting Mechthild of Magdeburg:

...since Thou hast taken from me all that I had of Thee, yet of Thy grace leave me the gift which every dog has by nature: that of being true to Thee in my distress, when I am deprived of all consolation. This I desire more fervently than Thy heavenly Kingdom.

And last she devotes a chapter to the unitive life, the sum of the mystic way:

When love has carried us above all things into the Divine Dark, there we are transformed by the Eternal Word Who is the image of the Father; and as the air is penetrated by the sun, thus we receive in peace the Incomprehensible Light, enfolding us, and penetrating us. (Ruysbroech)

Where Underhill struck new ground was in her insistence that this state of union produced a glorious and fruitful creativeness, so that the mystic who attains this final perfectness is the most active doer – not the reclusive dreaming lover of God.

We are all the kindred of the mystics. ..Strange and far away from us though they seem, they are not cut off from us by some impassable abyss. They belong to us; the giants, the heroes of our race. As the achievement of genius belongs not to itself only but also to the society that brought it forth;...the supernal accomplishment of the mystics is ours also. ..our guarantee of the end to which immanent love, the hidden steersman. ..is moving. ..us on the path toward the Real. They come back to us from an encounter with life's most august secret. ..filled with amazing tidings which they can hardly tell. We, longing for some assurance. ..urge them to pass on their revelation. ..the old demand of the dim-sighted and incredulous. ..But they cannot. ..only fragments of the Symbolic Vision. According to their strength and passion, these lovers of the Absolute. ..have not shrunk from the suffering. ..Beauty and agony have called. ..have awakened a heroic response. For them the winter is over. ..Life new, unquenchable and lovely comes to meet them with the dawn. (Cropper, p. 47)

The book ends with an extremely valuable appendix, a kind of who's who of mysticism, which shows its persistence and interconnection from century to century.

A work by Evelyn Underhill on the 14th-century Flemish mystic Jan van Ruusbroec (1293–1381), entitled Ruysbroeck, was published in London in 1914.[6] She had discussed him from several different perspectives during the course of her 1911 book on Mysticism.

I. Life. She starts with a biography, drawn mainly from two near-contemporary works on his life, each written by a fellow monastic: Pomerius,[7] and Gerard Naghel.[8]

His childhood was spent in the village of Ruysbroeck. [page 7] At eleven he ran away to Brussels, where he began to live with his uncle, John Hinckaert, a Canon at the Cathedral of St Gudule, and a younger Canon, Francis van Coudenberg. [10] At twenty-four he was ordained a priest and became a prebend at St. Gudule. [12] At his first mass he envisioned his mother's spirit released from Purgatory and entering Heaven. [15] From age 26 to 50 Ruysbroeck was a cathedral chaplain at St Gudule. [15] Although he "seemed a nobody to those who did not know him", he was developing a strong spiritual life, "a penetrating intellect, a fearless heart, deep knowledge of human nature, remarkable powers of expression". [17] At one point he wrote strong pamphlets and led a campaign against a heretical group, the Brethren of the Free Spirit led by Bloemardinne, who practiced a self-indulgent "mysticality". [18–20] Later, with the two now elderly Canons, he moved into the countryside at Groenendael ("Green Valley"). [21–22] Pomerius writes that he retired not to hide his light "but that he might tend it better" [22]. Five years later their community became a Priory under the Augustinian Canons. [23]

Many of his works were written during this period, often drawing lessons from nature. [24] He had a favourite tree, under which he would sit and write what the 'Spirit' gave to him. [25] He solemnly affirmed that his works were composed under the "domination of an inspiring power", writes Underhill. [26] Pomerius says that Ruysbroeck could enter a state of contemplation in which he appeared surrounded by radiant light. [26–27] Alongside his spiritual ascent, Naghel says, he cultivated the friendship of those around him, enriching their lives. [27–28] He worked in the garden fields of the priory, and sought to help out creatures of the forest. [29–30] He moved from the senses to the transcendent without frontiers or cleavage, Underhill writes, these being for him "but two moods within the mind of God". [30] He counseled many who came to him, including Gerard Groot of the Brothers of the Common Life. [31] His advice would plumb the "purity and direction" of the seeker's will, and the seeker's love. [32] There, at Groenendael, he finally made a "leap to a more abundant life". [34] In The Sparkling Stone Ruysbroeck wrote about coming to know the love "which giveth more than one can take, and asketh more than one can pay". [34]

II. Works. Next, Underhill gives a bibliography of Ruysbroeck's eleven admittedly authentic works, providing details on each work's origin, nature, and contents, as well as their place in his writings. 1. The Spiritual Tabernacle; 2. The Twelve Points of True Faith; 3. The Book of the Four Temptations; 4. The Book of the Kingdom of God's Lovers; 5. The Adornment of the Spiritual Marriage;[9] 6. The Mirror of Eternal Salvation or Book of the Blessed Sacraments; 7. The Seven Cloisters; 8. The Seven Degrees of the Ladder of Love; 9. The Book of the Sparkling Stone; 10. The Book of the Supreme Truth; 11. The Twelve Béguines. [36–51]

III. Doctrine of God. Several types of mystics are described. The first (e .g., St Teresa) deals with personal psychological experiences and emotional reactions, leaving the nature of God to existing theology. [page 52] The second (e. g., Plotinus) has passion sprung from the vision of a philosopher; the intellect often is more active than the heart, yet like a poet such a mystic strives to sketch his vision of the Ultimate. [53] The greatest mystics (e. g., St Augustine) embrace at once "the infinite and the intimate" so that "God is both near and far, and the paradox of transcendent-immanent Reality is a self-evident if an inexpressible truth." Such mystics "give us by turns a subjective and psychological, an objective and metaphysical, reading of spiritual experience." Here is Ruysbroeck. [53–54]

An apostolic mystic [55] represents humanity in its quest to discern the Divine Reality, she writes, being like "the artist extending our universe, the pioneer cutting our path, the hunter winning food for our souls." [56] Yet, although his experience is personal, his language is often drawn from tradition. [57] His words about an ineffable Nature of God, "a dim silence, and a wild desert," may be suggestive, musical, she writes, "which enchant rather than inform the soul". [58] Ruysbroeck goes venturing "to hover over that Abyss which is 'beyond Reason,' stammering and breaking into wild poetry in the desperate attempt to seize the unseizable truth." [55] "[T]he One is 'neither This nor That'." [61]

"God as known by man" is the Absolute One who combines and resolves the contradictory natures of time and eternity, becoming and being; who is both transcendent and immanent, abstract and personal, work and rest, the unmoved mover and movement itself. God is above the storm, yet inspires the flux. [59–60] The "omnipotent and ever-active Creator" who is "perpetually breathing forth His energetic Life in new births of being and new floods of grace." [60] Yet the soul may persist, go beyond this fruitful nature,[10] into the simple essence of God. There we humans would find that "absolute and abiding Reality, which seems to man Eternal Rest, the 'Deep Quiet of the Godhead,' the 'Abyss,' the 'Dim Silence'; and which we can taste indeed but never know. There, 'all lovers lose themselves'." [60]

The Trinity, according to Ruysbroeck, works in living distinctions, "the fruitful nature of the Persons." [61] The Trinity in itself is a Unity, yet a manifestation of the active and creative Divine, a Union of Three Persons, which is the Godhead. [60–61][11] Beyond and within the Trinity, or the Godhead, then, is the "fathomless Abyss" [60] that is the "Simple Being of God" that is "an Eternal Rest of God and of all created things." [61][12]

The Father is the unconditioned Origin, Strength and Power, of all things. [62] The Son is the Eternal Word and Wisdom that shines forth in the world of conditions. [62] The Holy Spirit is Love and Generosity emanating from the mutual contemplation of Father and Son. [62][13] The Three Persons "exist in an eternal distinction [emphasis added] for that world of conditions wherein the human soul is immersed". [63] By the acts of the Three Persons all created things are born; by the incarnation and crucifixion we human souls are adorned with love, and so to be drawn back to our Source. "This is the circling course of the Divine life-process." [63]

But beyond and above this eternal distinction lies "the superessential world, transcending all conditions, inaccessible to thought-- 'the measureless solitude of the Godhead, where God possesses Himself in joy.' This is the ultimate world of the mystic." [63–64] There, she continues, quoting Ruysbroeck:

"[W]e can speak no more of Father, Son and Holy Spirit nor of any creature; but only of one Being, which is the very substance of the Divine Persons. There were we all one before our creation; for this is our superessence... . There the Godhead is, in simple essence, without activity; Eternal Rest, Unconditioned Dark, the Nameless Being, the Superessence of all created things, and the simple and infinite Bliss of God and of all the Saints." [64][14]

"The simple light of this Being... includes and embraces the unity of the Divine Persons and the soul... ." It envelopes and irradiates the ground (movement) of human souls and the fruition of their adherence to God, finding union in the Divine life-process, the Rose. "And this is the union of God and the souls that love Him." [64–65][15]

IV. Doctrine of Humankind. For Ruysbroeck, "God is the 'Living Pattern of Creation' who has impressed His image on each soul, and in every adult spirit the character of that image must be brought from the hiddenness and realized." [66][16] The pattern is trinitarian; there are three properties of the human soul. First, resembling the Father, "the bare, still place to which consciousness retreats in introversion... ." [67] Second, following the Son, "the power of knowing Divine things by intuitive comprehension: man's fragmentary share in the character of the Logos, or Wisdom of God." [67–68] "The third property we call the spark of the soul. It is the inward and natural tendency of the soul towards its Source; and here do we receive the Holy Spirit, the Charity of God." [68].[17] So will God work within the human being; in later spiritual development we may form with God a Union, and eventually a Unity. [70–71][18]

The mighty force of Love is the "very self-hood of God" in this mysterious communion. [72, 73] "As we lay hold upon the Divine Life, devour and assimilate it, so in that very act the Divine Life devours us, and knits us up into the mystical Body," she writes. "It is the nature of love," says Ruysbroeck, "ever to give and to take, to love and be loved, and these two things meet in whomsoever loves. Thus the love of Christ is both avid and generous... as He devours us, so He would feed us. If He absorbs us utterly into Himself, in return He gives us His very self again." [75–76][19] "Hungry love," "generous love," "stormy love" touches the human soul with its Divine creative energy and, once we become conscious of it, evokes in us an answering storm of love. "The whole of our human growth within the spiritual order is conditioned by the quality of this response; by the will, the industry, the courage, with which [we accept our] part in the Divine give-and-take." [74] As Ruysbroeck puts it:

That measureless Love which is God Himself, dwells in the pure deeps of our spirit, like a burning brazier of coal. And it throws forth brilliant and fiery sparks which stir and enkindle heart and senses, will and desire, and all the powers of the soul, with a fire of love; a storm, a rage, a measureless fury of love. These be the weapons with which we fight against the terrible and immense Love of God, who would consume all loving spirits and swallow them in Himself. Love arms us with its own gifts, and clarifies our reason, and commands, counsels and advises us to oppose Him, to fight against Him, and to maintain against Him our right to love, so long as we may. [74–75][20]

The drama of this giving and receiving Love constitutes a single act, for God is as an "ocean which ebbs and flows" or as an "inbreathing and outbreathing". [75, 76] "Love is a unifying power, manifested in motion itself, 'an outgoing attraction, which drags us out of ourselves and calls us to be melted and naughted in the Unity'; and all his deepest thoughts of it are expressed in terms of movement." [76][21]

Next, the spiritual development of the soul is addressed. [76–88] Ruysbroeck adumbrates how one may progress from the Active life, to the Interior life, to the Superessential life; these correspond to the three natural orders of Becoming, Being, and God, or to the three rôles of the Servant, the Friend, and the "hidden child" of God. [77, 85] The Active life focuses on ethics, on conforming the self's daily life to the Will of God, and takes place in the world of the senses, "by means". [78] The Interior life embraces a vision of spiritual reality, where the self's contacts with the Divine take place "without means". [78] The Superessential life transcends the intellectual plane, whereby the self does not merely behold, but rather has fruition of the Godhead in life and in love, at work and at rest, in union and in bliss. [78, 86, 87][22] The analogy with the traditional threefold way of Purgation, Illumination, and Union, is not exact. The Interior life of Ruysbroeck contains aspects of the traditional Union also, while the Superessential life "takes the soul to heights of fruition which few amongst even the greatest unitive mystics have attained or described." [78–79]

At the end of her chapter IV, she discusses "certain key-words frequent in Ruysbroeck's works," e.g., "Fruition" [89], "Simple" [89–90], "Bareness" or "Nudity" [90], and "the great pair of opposites, fundamental to his thought, called in the Flemish vernacular wise and onwise." [91–93][23] The wise can be understood by the "normal man [living] within the temporal order" by use of "his ordinary mental furniture". [91] Yet regarding the onwise he has "escaped alike from the tyrannies and comforts of the world" and made the "ascent into the Nought". [92][24] She comments, "This is the direct, unmediated world of spiritual intuition; where the self touches a Reality that has not been passed through the filters of sense and thought." [92] After a short quote from Jalālu'ddīn, she completes her chapter by presenting 18 lines from Ruysbroeck's The Twelve Bêguines (cap. viii) which concern Contemplation:

- Contemplation is a knowing that is in no wise ...

- Never can it sink down into the Reason,

- And above it can the Reason never climb. ...

- It is not God,

- But it is the Light by which we see Him.

- Those who walk in the Divine Light of it

- Discover in themselves the Unwalled.

- That which is in no wise, is above Reason, not without it ...

- The contemplative life is without amazement.

- That which is in no wise sees, it knows not what;

- For it is above all, and is neither This nor That. [93]

V, VI, VII, VIII. In her last four chapters, Underhill continues her discussion of Ruysbroeck, describing the Active Life [94–114], the Interior Life (Illumination and Destitution [115–135], Union and Contemplation [136–163]), and the Superessential Life [164–185].[25]

"The Mysticism of Plotinus" (1919)[edit source]

An essay originally published in The Quarterly Review (1919),[26] and later collected in The Essentials of Mysticism and other essays (London: J. M. Dent 1920) at pp. 116–140.[27] Underhill here addresses Plotinus (204–270) of Alexandria and later of Rome.

A Neoplatonist as well as a spiritual guide, Plotinus writes regarding both formal philosophy and hands-on, personal, inner experience. Underhill makes the distinction between the geographer who draws maps of the mind, and the seeker who actually travels in the realms of spirit. [page 118] She observes that usually mystics do not follow the mere maps of metaphysicians. [page 117]

In the Enneads Plotinus presents the Divine as an unequal triune, in descending order: (a) the One, perfection, having nothing, seeking nothing, needing nothing, yet it overflows creatively, the source of being; [121] (b) the emitted Nous or Spirit, with intelligence, wisdom, poetic intuition, the "Father and Companion" of the soul; [121–122] and, (c) the emitted Soul or Life, the vital essence of the world, which aspires to communion with the Spirit above, while also directly engaged with the physical world beneath. [123]

People "come forth from God" and will find happiness once re-united, first with the Nous, later with the One. [125] Such might be the merely logical outcome for the metaphysician, yet Plotinus the seeker also presents this return to the Divine as a series of moral purgations and a shedding of irrational delusions, leading eventually to entry into the intuitively beautiful. [126] This intellectual and moral path toward a life aesthetic will progressively disclose an invisible source, the Nous, the forms of Beauty. [127] Love is the prevailing inspiration, although the One is impersonal. [128] The mystic will pass through stages of purification, and of enlightenment, resulting in a shift in the center of our being "from sense to soul, from soul to spirit," in preparation for an ultimate transformation of consciousness. [125, 127] Upon our arrival, we shall know ecstasy and "no longer sing out of tune, but form a divine chorus round the One." [129]

St. Augustine (354–430) criticizes such Neoplatonism as neglecting the needs of struggling and imperfect human beings. The One of Plotinus may act as a magnet for the human soul, but it cannot be said to show mercy, nor to help, or love, or redeem the individual on earth. [130] Other western mystics writing on the Neoplatonists mention this lack of "mutual attraction" between humanity and the unconscious, unknowable One. [130–131] In this regard Julian of Norwich (1342–1416) would write, "Our natural will is to have God, and the good-will of God is to have us." [130]

Plotinus leaves the problem of evil unresolved, but having no place in the blissful life; here, the social, ethical side of religion seems to be shorted. His philosophy does not include qualities comparable to the Gospel's divine "transfiguration of pain" through Jesus. [131] Plotinus "the self-sufficient sage" does not teach us charity, writes St. Augustine. [132]

Nonetheless, Underhill notes, Plotinus and Neoplatonism were very influential among the mystics of Christianity (and Islam). St. Augustine the Church Father was himself deeply affected by Plotinus, and through him the western Church. [133–135, 137] So, too, was Dionysius (5th century, Syria), whose writings would also prove very influential. [133, 135] As well were others, e.g., Erigena [135], Dante [136], Ruysbroeck [136, 138], Eckhart [138], and Boehme [139].

In her preface,[28] the author disclaims being "a liturgical expert". Neither is it her purpose to offer criticism of the different approaches to worship as practiced by the various religious bodies. Rather she endeavors to show "the love that has gone to their adornment [and] the shelter they can offer to many different kinds of adoring souls." She begins chapter one by declaring that "Worship, in all its grades and kinds, is the response of the creature to the Eternal: nor need we limit this definition to the human sphere. ...we may think of the whole of the Universe, seen and unseen, conscious and unconscious, as an act of worship."

The chapter headings give an indication of their contents.

- Part I: 1. The Nature of Worship, 2. Ritual and Symbol, 3. Sacrament and Sacrifice, 4. The Character of Christian Worship, 5. Principles of Corporate Worship, 6. Liturgical Elements in Worship, 7. The Holy Eucharist: Its Nature, 8. The Holy Eucharist: Its Significance, 9. The Principles of Personal Worship.

- Part II: 10. Jewish Worship, 11. The Beginnings of Christian Worship, 12. Catholic Worship: Western and Eastern, 13. Worship in the Reformed Churches, 14. Free Church Worship, 15. The Anglican Tradition. Conclusion.

Underhill's life was greatly affected by her husband's resistance to her joining the Catholic Church, to which she was powerfully drawn. At first she believed it to be only a delay in her decision, but it proved to be lifelong. He was, however, a writer himself and was supportive of her writing both before and after their marriage in 1907, though he did not share her spiritual affinities. Her fiction was written in the six years of 1903–1909 and represents her four major interests of that general period: philosophy (neoplatonism), theism/mysticism, the Roman Catholic liturgy, and human love/compassion.[29] In her earlier writings Underhill often wrote using the terms "mysticism" and "mystics" but later began to adopt the terms "spirituality" and "saints" because she felt they were less threatening. She was often criticized for believing that the mystical life should be accessible to the average person.

Her fiction was also influenced by the literary creed expounded by her close friend Arthur Machen, mainly his Hieroglyphics of 1902, summarised by his biographer:

There are certain truths about the universe and its constitution – as distinct from the particular things in it that come before our observation – which cannot be grasped by human reason or expressed in precise words: but they can be apprehended by some people at least, in a semi-mystical experience, called ecstasy, and a work of art is great insofar as this experience is caught and expressed in it. Because, however, the truths concerned transcend a language attuned to the description of material objects, the expression can only be through hieroglyphics, and it is of such hieroglyphics that literature consists.

In Underhill's case the quest for psychological realism is subordinate to larger metaphysical considerations which she shared with Arthur Machen. Incorporating the Holy Grail into their fiction (stimulated perhaps by their association with Arthur Waite and his affiliation with the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn), for Machen the Holy Grail was perhaps "the" hieroglyph, "the" crystallisation in one sacred emblem of all man's transcendental yearning, "the" gateway to vision and lasting appeasement of his discontents, while for her it was the center of atonement-linked meanings as she pointed out to Margaret Robinson in a letter responding to Robinson's criticism of Underhill's last novel:

Don't marvel at your own temerity in criticising. Why should you? Of course, this thing wasn't written for you – I never write for anyone at all, except in letters of direction! But, I take leave to think the doctrine contained in it is one you'll have to assimilate sooner or later and which won't do you any harm. It's not "mine" you know. You will find it all in Eckhart. ... They all know, as Richard of St Victor said, that the Fire of Love "burns." We have not fulfilled our destiny when we have sat down at a safe distance from it, purring like overfed cats, 'suffering is the ancient law of love' – and its highest pleasure into the bargain, oddly enough. ... A sponge cake and milk religion is neither true to this world nor to the next. As for the Christ being too august a word for our little hardships – I think it is truer that it is "so" august as to give our little hardships a tincture of Royalty once we try them up into it. I don't think a Pattern which was 'meek & lowly' is likely to fail of application to very humble and ordinary things. For most of us don't get a chance "but" the humble and ordinary: and He came that we might all have life more abundantly, according to our measure. There that's all![30]

Two contemporary philosophical writers dominated Underhill's thinking at the time she wrote "Mysticism": Rudolf Eucken and Henri Bergson. While neither displayed an interest in mysticism, both seemed to their disciples to advance a spiritual explanation of the universe. Also, she describes the fashionable creed of the time as "vitalism" and the term adequately sums up the prevailing worship of life in all its exuberance, variety and limitless possibility which pervaded pre-war culture and society. For her, Eucken and Bergson confirmed the deepest intuitions of the mystics. (Armstrong, Evelyn Underhill)

Among the mystics, Ruysbroeck was to her the most influential and satisfying of all the medieval mystics, and she found herself very much at one with him in the years when he was working as an unknown priest in Brussels, for she herself had also a hidden side.

His career which covers the greater part of the fourteenth century, that golden age of Christian Mysticism, seems to exhibit within the circle of a single personality, and carry up to a higher term than ever before, all the best attainments of the Middle Ages in the realm of Eternal life. The central doctrine of the Divine Fatherhood, and of the soul's power to become the Son of God, it is this raised to the nth degree of intensity...and demonstrated with the exactitude of the mathematician, and the passion of a poet, which Ruysbroeck gives us...the ninth and tenth chapters of The Sparkling Stone the high water mark of mystical literature. Nowhere else do we find such a combination of soaring vision with the most delicate and intimate psychological analysis. The old Mystic sitting under his tree, seems here to be gazing at and reporting to us the final secrets of that Eternal World... (Cropper, p. 57)

One of her most significant influences and important collaborations was with the Nobel Laureate, Rabindranath Tagore, the Indian mystic, author, and world traveler. They published a major translation of the work of Kabir (100 Poems of Kabir, calling Songs of Kabir) together in 1915, to which she wrote the introduction. He introduced her to the spiritual genius of India which she expressed enthusiastically in a letter:

This is the first time I have had the privilege of being with one who is a Master in the things I care so much about but know so little of as yet: & I understand now something of what your writers mean when they insist on the necessity and value of the personal teacher and the fact that he gives something which the learner cannot get in any other way. It has been like hearing the language of which I barely know the alphabet, spoken perfectly.(Letters)

They did not keep up their correspondence in later years. Both suffered debilitating illnesses in the last year of life and died in the summer of 1941, greatly distressed by the outbreak of World War II.

Evelyn in 1921 was to all outward appearances, in an assured and enviable position. She had been asked by the University of Oxford to give the first of a new series of lectures on religion, and she was the first woman to gain such an honour. She was an authority on her own subject of mysticism and respected for her research and scholarship. Her writing was in demand, and she had an interesting and notable set of friends, devoted readers, a happy marriage and affectionate and loyal parents. At the same time she felt that her foundations were insecure and that her zeal for Reality was resting on a basis that was too fragile.

By 1939, she was a member of the Anglican Pacifist Fellowship, writing a number of important tracts expressing her anti-war sentiment.

After returning to the Anglican Church, and perhaps overwhelmed by her knowledge of the achievements of the mystics and their perilous heights, her ten-year friendship with Catholic philosopher and writer Baron Friedrich von Hügel turned into one of spiritual direction. Charles Williams wrote in his introduction to her Letters: 'The equal swaying level of devotion and scepticism (related to the church) which is, for some souls, as much the Way as continuous simple faith is to others, was a distress to her...She wanted to be "sure." Writing to Von Hügel of the darkness she struggled with:

What ought I to do?...being naturally self-indulgent and at present unfortunately professionally very prosperous and petted, nothing will get done unless I make a Rule. Neither intellectual work nor religion give me any real discipline because I have a strong attachment to both. ..it is useless advising anything people could notice or that would look pious. That is beyond me. In my lucid moments I see only too clearly that the only possible end of this road is complete, unconditional self-consecration, and for this I have not the nerve, the character or the depth. There has been some sort of mistake. My soul is too small for it and yet it is at bottom the only thing that I really want. It feels sometimes as if, whilst still a jumble of conflicting impulses and violent faults I were being pushed from behind towards an edge I dare not jump over."[31]

In a later letter of 12 July the Baron's practical concerns for signs of strain in Evelyn's spiritual state are expressed. His comments give insight into her struggles:

I do not at all like this craving for absolute certainty that this or that experience of yours, is what it seems to yourself. And I am assuredly not going to declare that I am absolutely certain of the final and evidential worth of any of those experiences. They are not articles of faith. .. You are at times tempted to scepticism and so you long to have some, if only one direct personal experience which shall be beyond the reach of all reasonable doubt. But such an escape. ..would ...possibly be a most dangerous one, and would only weaken you, or shrivel you, or puff you up. By all means...believe them, if and when they humble and yet brace you, to be probably from God. But do not build your faith upon them; do not make them an end when they exist only to be a means...I am not sure that God does want a marked preponderance of this or that work or virtue in our life – that would feed still further your natural temperament, already too vehement. (Cropper biography)

Although Underhill continued to struggle to the end, craving certainty that her beatific visions were purposeful, suffering as only a pacifist can from the devastating onslaught of World War II and the Church's powerlessness to affect events, she may well have played a powerful part in the survival of her country through the influence of her words and the impact of her teachings on thousands regarding the power of prayer. Surviving the London Blitz of 1940, her health disintegrated further and she died in the following year. She is buried with her husband in the churchyard extension at St John-at-Hampstead in London.

More than any other person, she was responsible for introducing the forgotten authors of medieval and Catholic spirituality to a largely Protestant audience and the lives of eastern mystics to the English-speaking world. As a frequent guest on radio, her 1936 work The Spiritual Life was especially influential as transcribed from a series of broadcasts given as a sequel to those by Dom Bernard Clements on the subject of prayer. Fellow theologian Charles Williams wrote the introduction to her published Letters in 1943, which reveal much about this prodigious woman. Upon her death, The Times reported that on the subject of theology, she was "unmatched by any of the professional teachers of her day."

Evelyn Underhill is honored on June 15th on the liturgical calendars of several Anglican churches, including those of the Anglican Church of Australia, Anglican Church in Aotearoa, New Zealand and Polynesia, Episcopal Anglican Church of Brazil, Church of England, Episcopal Church in the United States of America, and Anglican Church in North America.

- The Bar-Lamb's Ballad Book (1902). Online

- Immanence (1916). Online

- Theophanies (1916). Online

Religion (non-fiction)[edit source]

- The Miracles of Our Lady Saint Mary: Brought Out of Divers Tongues and Newly Set Forth in English (1906) Online

- Mysticism: A Study of the Nature and Development of Man's Spiritual Consciousness (1911). Twelfth edition published by E. P. Dutton in 1930. Republished by Dover Publications in 2002 (ISBN 978-0-486-42238-1). See also online editions at Christian Classics Ethereal Library and at Wikisource

- The Path of Eternal Wisdom. A mystical commentary on the Way of the Cross (1912)

- "Introduction" to her edition of the anonymous The Cloud of Unknowing (c. 1370) from the British Library manuscript [here entitled A Book of Contemplation the which is called the Cloud of Unknowing, in the which a Soul is oned with God] (London: John M. Walkins 1912); reprinted as Cloud of Unknowing (1998) [her "Introduction" at 5–37]; 2007: ISBN 1-60506-228-6; see her text at Google books

- The Spiral Way. Being a meditation on the fifteen mysteries of the soul's ascent (1912)

- The Mystic Way. A psychological study of Christian origins (1914). Online

- Practical Mysticism. A Little Book for Normal People (1914); reprint 1942 (ISBN 0-7661-0141-X); reprinted by Vintage Books, New York 2003 [with Abba (1940)]: ISBN 0-375-72570-9; see text at Wikisource.

- Ruysbroeck (London: Bell 1915). Online

- "Introduction" to Songs of Kabir (1915) transl. by Rabindranath Tagore; reprint 1977 Samuel Weiser (ISBN 0-87728-271-4), text at 5–43

- The Essentials of Mysticism and other essays (1920); another collection of her essays with the same title 1995, reprint 1999 (ISBN 1-85168-195-7)

- The Life of the Spirit and the Life of Today (1920). Online

- The Mystics of the Church (1925)

- Concerning the Inner Life (1927); reprint 1999 (ISBN 1-85168-194-9) Online

- Man and the Supernatural. A study in theism (1927)

- The House of the Soul (1929)

- The Light of Christ (1932)

- The Golden Sequence. A fourfold study of the spiritual life (1933)

- The School of Charity. Meditations on the Christian Creed (1934); reprinted by Longmans, London 1954 [with M.of S. (1938)]

- Worship (1936)

- The Spiritual Life (1936); reprint 1999 (ISBN 1-85168-197-3); see also online edition

- The Mystery of Sacrifice. A study on the liturgy (1938); reprinted by Longmans, London 1954 [with S.of C. (1934)]

- Abba. A meditation on the Lord's Prayer (1940); reprint 2003 [with Practical Mysticism (1914)]

- The Letters of Evelyn Underhill (1943), as edited by Charles Williams; reprint Christian Classics 1989: ISBN 0-87061-172-0

- Shrines and Cities of France and Italy (1949), as edited by Lucy Menzies

- Fragments from an inner life. Notebooks of Evelyn Underhill (1993), as edited by Dana Greene

- The Mysticism of Plotinus (2005) Kessinger offprint, 48 pages. Taken from The Essentials of Mysticism (1920)

- Fruits of the Spirit (1942) edited by R. L. Roberts; reprint 1982, ISBN 0-8192-1314-4

- The letters of Evelyn Underhill (1943) edited with an intro. by Charles Williams

- Collected Papers of Evelyn Underhill (1946) edited by L. Menzies and introduced by L. Barkway

- Lent with Evelyn Underhill (1964) edited by G. P. Mellick Belshaw

- An Anthology of the Love of God. From the writings of Evelyn Underhill (1976) edited by L. Barkway and L. Menzies

- The Ways of the Spirit (1990) edited by G. A. Brame; reprint 1993, ISBN 0-8245-1232-4

- Evelyn Underhill. Modern guide to the ancient quest for the Holy (1988) edited and introduced by D. Greene

- Evelyn Underhill. Essential writings (2003) edited by E. Griffin

- Radiance: A Spiritual Memoir (2004) edited by Bernard Bangley, ISBN 1-55725-355-2

- ^ Dana Greene (2004). "Underhill [married name Stuart Moore], Evelyn Maud Bosworth (1875–1941)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d Armstrong, C. J. R., "Evelyn Underhill: An Introduction to Her Life and Writings", A.R. Mowbray & Co., 1975.

- ^ Williams, Charles, editor, The Letters of Evelyn Underhill, Longmans Green, pp. 122–23.

- ^ Underhill, E., The Grey World, London: William Heinemann, 1904.

- ^ Underhill, E., The Column of Dust, London: Methuen & Co., 1909

- ^ By G. Bell & Sons; since reprinted [no date, circa 2003] by Kessinger Publishing.

- ^ Canon Henricus Pomerius was prior of the monastery where Ruysbroeck resided, but two generations later; he spoke with several of those who had known Ruysbroeck well [pages 5–6] and may have based his history on the work of a contemporary of Ruysbroek.

- ^ Gerard Naghel was a contemporary and a close friend of Ruysbroeck, as well as being the neighbouring prior; he wrote a shorter work about his life [6].

- ^ Also known as The Spiritual Espousals (e. g., Wiseman's translation in his John Ruusbroec (Paulist Press 1985); it is "the best known" of Ruysbroeck's works. [42].

- ^ "Fruition is one of the master-words of Ruysbroeck's thought," she observes. [page 59] Later she more fully discusses it, at [89].

- ^ Here, she comments, Ruysbroeck parallels the Hindu mystics, the Christian Neoplatonists, and Meister Eckhart. [61]

- ^ She quotes from The Twelve Béguines at cap. xiv.

- ^ "[F]or these two Persons are always hungry for love," she adds, quoting The Spiritual Marriage, lib. ii at cap. xxxvii.

- ^ She gives her source as The Seven Degrees of Love at cap. xiv.

- ^ She quotes from The Kingdom of God's Lovers at cap. xxix.

- ^ Evelyn Underhill here refers to Julian of Norwich and quotes her phrase on the human soul being "made Trinity, like to the unmade Blessed Trinity." Then she makes the comparison of Ruysbroeck's uncreated Pattern of humanity to an archetype, and to a Platonic Idea. [68].

- ^ Here she quotes The Mirror of Eternal Salvation at cap. viii. Cf., [70].

- ^ She quotes Ruysbroeck, The Book of Truth at cap. xi, "[T]his union is in God, through grace and our homeward-tending love. Yet even here does the creature feel a distinction and otherness between itself and God in its inward ground." [71].

- ^ Quoting The Mirror of Eternal Salvation at cap. vii. She refers here to St. Francis of Assisi.

- ^ She again quotes from The Mirror of Eternal Salvation at cap. xvii.

- ^ Ruysbroeck, The Sparkling Stone at cap. x: quoted.

- ^ Re the Superessential life, citing The Twelve Béguines at cap. xiii [86]; and, The Seven Degrees of Love at cap. xiv [87].

- ^ These opposites are variously translated into English, Underhill sometimes favouring "in some wise" and "in no wise" or "conditioned' and "unconditioned" or "somehow" and "nohow". That is, the second opposite onwise she gives it translated as no wise [93]. Cf., "Superessential" [85 & 86–87; 90–91].

- ^ Ruysbroeck, The Twelve Bêguines at cap. xii.

- ^ As mentioned, Underhill earlier addressed how Ruysbroeck distinguishes the Active, Interior, and Superessential at pages 76–88 in her book.

- ^ QR (1919), pp. 479–497.

- ^ Recently offprinted by Kessinger Publishing as The Mysticism of Plotinus (2005), 48 pp.

- ^ Evelyn Underhill, Worship (New York: Harper and Brothers 1936; reprint Harper Torchbook 1957) pp. vii–x.

- ^ name="Armstrong, C.J.R."

- ^ Armstrong, C. J. R., Evelyn Underhill: An Introduction to her Life and Writings, pp. 86–87, A. R. Mowbray & Co., 1975

- ^ Cropper, Margaret, Life of Evelyn Underhill, Harper & Brothers, 1958

- A. M. Allchin, Friendship in God - The Encounter of Evelyn Underhill and Sorella Maria of Campello (SLG Press, Fairacres Oxford 2003)

- Margaret Cropper, The Life of Evelyn Underhill (New York 1958)

- Christopher J. R. Armstrong, Evelyn Underhil (1875–1941). An introduction to her life and writings (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans 1976)

- Michael Ramsey and A. M. Allchin, Evelyn Underhill. Two centenary essays (Oxford 1977)

- Annice Callahan, Evelyn Underhill: Spirituality for daily living (University Press of America 1997)

- Dana Greene, Evelyn Underhill. Artist of the infinite life (University of Notre Dame 1998)

(3.75) None

(3.75) None )

)

drsabs | Feb 24, 2014 |

drsabs | Feb 24, 2014 |

A sculpture of Meister Eckhart in Germany.

A sculpture of Meister Eckhart in Germany.  A sculpture of Meister Eckhart in Germany.

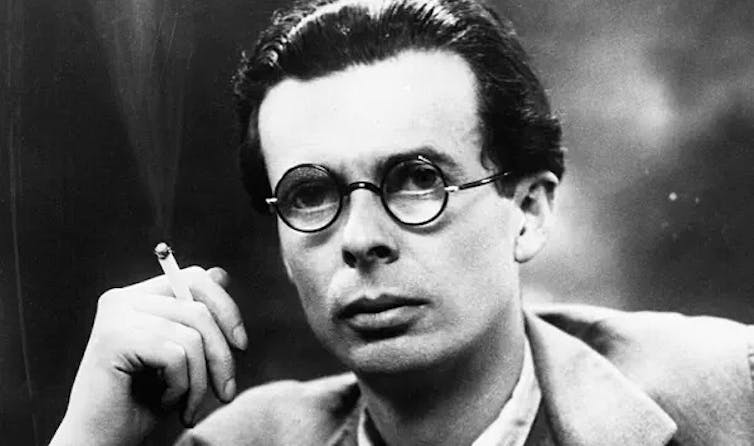

A sculpture of Meister Eckhart in Germany.  Novelist Aldous Huxley frequently cited Eckhart, in his book, ‘The Perennialist Philosophy.’

Novelist Aldous Huxley frequently cited Eckhart, in his book, ‘The Perennialist Philosophy.’