I. A Historical Sketch

II. Ch’an Spirituality

Thomas P. Kasulis

III. Four Ch’an Masters

Dale S. Wright

IV. The Encounter of Ch’an with Confucianism

Robert E. Buswell, Jr.

Henrik H. Sorensen

I. The Birth of Japanese Buddhism

II. The Impact of Buddhism in the Nara Period

Thomas P. Kasulis

III. The Japanese Transformation of Buddhism

I. Saicho

II. Kukai

Paul B. Watt

III. Heian Foundation of Kamakura Buddhism

I. Early Pure Land Leaders

III. Shinran’s Way

I. A Historical Sketch

II. Dogen

III. Three Zen Thinkers

I. Buddhist Responses to Confucianism

II. The Buddhist Element in Shingaku

Paid B. Watt

III. Jiun Sonja

Paul B. Watt

. 417

Philosophy as Spirituality

The Way of the Kyoto School

James W H e i s i g

I N THE EIRST OE A series of talks delivered on Basel radio in 1949, Karl

Jaspers described philosophy as the concentrated effort to ecome

oneself by participating in reality;* 1 For the historian of the Western

intellectual tradition, the description may seem to exaggerate t e

importance of only one ingredient in the practice of philosop iy, ut it

applies well to the group of Japanese thinkers known as the Kyoto sc oo .

Their pursuit of philosophical questions was never detached from t e cu ti

vation of human consciousness as participation in the real. Drawing on

Western philosophy ancient and modern as well as on their ov\ n Bu 11 st

heritage, and combining the demands of critical thought with the quest or

religious wisdom, they have enriched world intellectual history wit a res

Japanese perspective and opened anew the question of the spiritua i men

sion of philosophy. In this article I would like to focus on this re igious

significance of their achievement.

It might be thought that the philosophy of the Kyoto school is inaccessi

ble to those not versed in the language, religion, and culture of Japan. Rea

in translation, there is a certain strangeness to the vocabulary, and many o

the sources these thinkers take for granted will be unfamiliar. They pre

suppose the education and reading habits of their Japanese audience, so

that many subtleties of style and allusion, much of what is going on

between the lines and beneath the surface of their texts, will inevitab y e

lost on other audiences. Still, it was not their aim to produce a merely Bu

dhist, much less Japanese, body of thought, but rather to address funda

mental, universal issues in what they saw as the universally accessible lan¬

guage of philosophy. That is why their work has proved intelligible and

367

368

JAPAN

accessible far beyond Japan, and why it is prized today by many Western

readers as an enhancement of the spiritual dimension of our common

•humanity.

Opinions differ on how to define the membership of the Kyoto school,

but there is no disagreement that its main pillars are Nishida Kitaro

( 1870 -1945) and his disciples, Tanabe Hajime (1885-1962) and Nishitani

Keiji (1900—1990), all of whom held chairs at Kyoto University. Similari¬

ties in interest and method, as well as significant differences among the

three, are best understood by giving each a brief but separate treatment.

Nishida Kitaro: The Quest of the Locus of Absolute Nothingness

For Nishida the goal of the philosophical enterprise was self-awakening: to

t e phenomena of life clearly through recovering the original purity of

experience to articulate rationally what has been seen, and to reappraise

i eas t at govern human history and society with reason thus enlight-

^ r ^ nce realit y ls constantly changing, and since we are part

t at c ange, unde)standing must be a “direct experiencing from within”

« lCU a * l °n °f what has been so understood must be an internalized,

°P nate expression. Accordingly, Nishida’s arguments are often post

murk k StI *n Ct j ( j? S a P at ^ of thinking he had traversed intuitively, led as

absorbin ^ ^ ^ SCnSe rea ^ c y as by the Western philosophies he was

A o •

a flv npfl r k- t0 aV T e een struc ^ one da y while on a walk by the buzzing of

confirmed ^ ^ ou £hts, he only “noticed” it later, but this

and are krp lm * , C ord i nar iness of the experience where things happen

brines the r n0tlCed accordi ng to biased habits of thought. “I heard a fly”

between an Xand "X’-X 10 ^ prOCess distorts >nto a relationship

saw actualiri^ a y * event is pure actuality. Somehow, he

atel’y distract COnStIt . Ute SUbjeCtS ° b i ects > but then mind is immedi '

purity of the n * ° ^ S * S and i ud £ men t, never to find its way back to the

ter mind from t-k ex P er * ence - To recover that purity would be to unfet-

nicating the experience?'^ COnst [ aints of bein S reasonable or of commu-

that mind leans f r 1 °' ° Se wbo d ‘ d not sbare it. This does not mean

PlyXt W Z r. e S c nSeS t0 SOme privile S ed -errant state, but sim-

what can onlv h ^ .!™, ltS ,° ltS Unbound, bodily existence, mind reaches

what can only be called a kind of boundlessness.

da’s starri experience prior to the subject-object distinction was Nishi-

a clea r ? COurses throu S h the pages of his collected works like

stream. In the opening pages of his maiden work, A Study of the Good,

PHILOSOPHY AS SPIRITUALITY

369

Nishida calls it “pure experience,” borrowing a term from the American

philosopher William James. His attraction to the idea, however, stems less

from James, or indeed from any Western thinker, than from his own Sino-

Japanese tradition. We read, for instance, in the eleventh-century Buddhist

Record of the Transmission of the Lamp that “the mental state having achieved

true enlightenment is like that before enlightenment began”; or again, the

great Noh dramatist Zeami (1363-1443) comments on how the Book of

Changes deliberately omits the element for “mind” in the Chinese glyph for

“sensation” to indicate a precognitive awareness. 4 Such was the tradition

out of which Nishida stepped into his study of philosophy and forged what

he was later to call his “logic of locus.” 5

The Logic of Locus

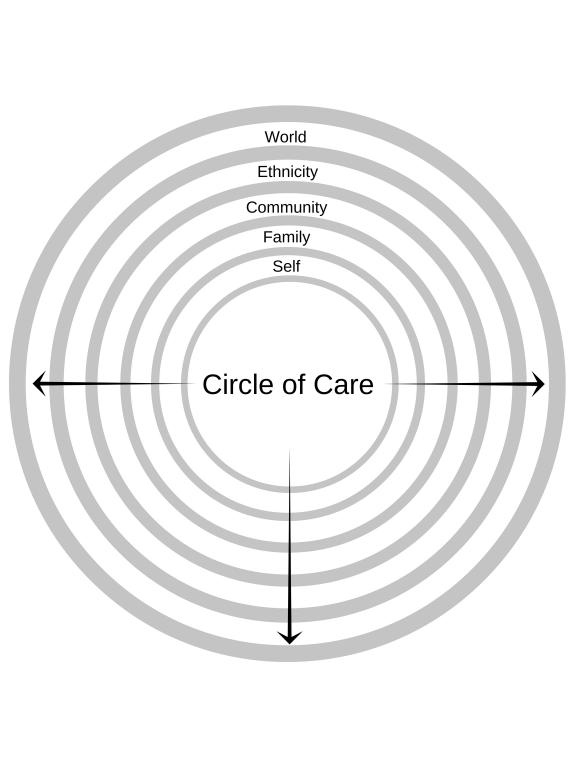

In its forward, rational construction, the process of restoring experience to

its purity—the aim of the logic of locus—may be described graphically as

a series of concentric circles. 6 The smallest circle, where the center is most

in control of the periphery, is that of a judgment where something is pred¬

icated of a particular subject. (Japanese does not suffer the ambiguity of the

term “subject” here as Germanic and Latin languages do, where the gram¬

matical subject is easily confused with the subject who makes the judg¬

ment.) Thus “The rose is red” is like a small galaxy with the rose at the cen¬

ter and redness revolving about it like a planet. Nishida interpreted Aris¬

totle’s logic of predication as focused on the subject, which provides a sta¬

ble center of gravity for its attributes and the comprehension of which

grows as more and more attributes are given orbit about it. Nishida sought

for his own logic the same solid foundation that Aristotle's “subject that

could not become a predicate,” provided, but without the metaphysical

nuisance of “substance.” To do so, he reversed the emphasis by following

the predicates. In other words, he shifted his attention away from expand¬

ing description or analysis of the object to releasing predication from the

subject-object framework in order to see where the process itself takes

place.”

As reported by his students, he would then draw a second circle on the

blackboard surrounding the first, opening the field for other predicating

judgments. The galaxy of particular judgments is now seen to rest in a larger

universe where the original, grammatical subject has forfeited its position

of centrality to the thinking subject who makes the judgment in the first

place. This is the locus of reflective consciousness. It is not the world; nor is

it even experience of the world. It is the consciousness where judgments

370

JAPAN

about the world are located—indeed where all attempts to know and con¬

trol reality by locating it within the limits of the thinking processes of

human beings find their homeground.

The predicate “red” is no longer bound to some particular object, and

particular objects are no longer limited by their satellite attributes or the

language that encases them. Everything is seen as relative to the process of

constructing the world in mind. The move to this wider circle shows judg¬

ment to be a finite act within a larger universe of thinking.

This gives rise to the next question: And just where is this consciousness

itself located? If mind is a field of circumstances that yield judgments, what

are the circumstances that define mind? To locate them deeper within the

mind would be like Baron Munchausen pulling himself out of the swamp

by his own pigtail. Recourse to the idea of a higher subject for which ordi¬

nary consciousness is an object is a surrender to infinite regress. Still, if the

notions of subject and object only set the boundaries for conscious judg¬

ment, this does not preclude the possibility of a still higher level of aware¬

ness that will envelop the realm of subjects and objects.

To show this, Nishida drew another circle about the first two, a broad one

with broken lines to indicate a location unbounded and infinitely expand¬

able (though not, of necessity, infinitely expanded), a place he called “noth¬

ingness. This was his absolute, deliberately so named to replace the

a solute of being in much Western philosophy. Being, for Nishida, cannot

e a solute because it can never be absolved from the relationships that

ne it. The true absolution had to be—as the Japanese glyphs zettai indi¬

te cut off from any and every “other.” Absoluteness precludes all

subject and object, all bifurcation of one thing from another,

all individuation of one mind or another.

is defined by its unboundedness, this place of absolute nothingness

f lAlf ° CUS r ° 1 sa * vat i° n > °f deliverance from time and being. It is the

ment o t e philosophical-religious quest where the action of intuition

sciousness take place without an acting subject and in the immedi-

^ c mornent > where the self working on the world yields to a pure

, 4 ^- ° aS lt lS ' * C iS moment of enlightenment that is right at

an in t e ere an -now, all-at-once-ness of experience. The final circle is

t us on e w ose circumference is nowhere and whose center can be any-

W L CrC ; C lma &^ was ta ken from Cusanus, but the insight behind it was

there in Nishida from the start.

In fact, over the years Nishida employed a number of idioms to express

sel f- awa ren ess at the locus of absolute nothingness, among them: “appro-

priation, acting intuition, seeing without a seer,” and “knowing a thing

PHILOSOPHY AS SPIRITUALITY

371

by becoming that thing.” In his early writings he is somewhat inhibited by

Neo-Kantian epistemological conundrums, but he advances steadily to an

integrated view ol how consciousness takes shape, with a Hegelian empha¬

sis on its embeddedness in the historical praxis of a bodily agent. He comes

to see knowing not as the activity of a self-empowered subject but as “act¬

ing intuition” in which the very idea of the subject grasping objects has

been superseded. This intuition is no longer a spying on reality as the ulti¬

mate “other,” but a participation in the self-actualization of reality itself. In

other words, awareness of the unbounded, absolute character of nothing¬

ness which arises out of reflection on immediate experience is not meant to

detach the subject from the real world but to insinuate its presence still

deeper there. “True reality,” he writes, “is not the object of dispassionate

knowing— Without our feelings and will, the actual world ceases to be a

concrete fact and becomes mere abstract concept.” 7

This idea of participating in reality by overcoming the subject-object

dichotomy was given logical form by Nishida in a deliberately ambivalent

formula that can be read “an absolute self-identity of contradictories or a

self-identity of absolute contradictories.” The Japanese apposition allows for

both and he made free use of the double-entendre , depending on whether he

wished to stress the radical nature of the identity achieved or the radical

opposition of the elements that go into the identity. A further ambiguity in

the formula, less transparent in the texts, is the qualification of the identi¬

ty as a j^-identity. For one thing, the identity is automatic. It is not induced

from without, nor is it forced on a stubborn, resistant reality. It takes place

when the limitations of the narrow circles of subject-predicate and subject-

object are overcome. Here “identity” refers to the way reality is, minus the

interference of reflective mind, and the way the mind is when lit up by real¬

ity. At the same time, the true identity of reality is not independent of that

of the true, awakened self. It is not that the self is constructed one way and

the world another; or that the deepest truth of the self is revealed by

detaching itself from the world. The apparently absolute opposition

between the two is only overcome when the individual is aware that “every

act of consciousness is a center radiating in infinity ” 8 —that is, out into the

circumferenceless circle of nothingness.

In all these reflections Nishida is pursuing a religious quest, a summation

of which he attempted in a rambling final essay, “The Logic of Locus and a

Religious Worldview.” We see Nishida, on the one hand, at pains to clarify

the roots of his logic of locus in Buddhist thought; on the other, to clarify

his understanding of religion as not bound to any particular historical tra¬

dition. Religion is not ritual or institution, or even morality. It is “an event

372

JAPAN

of the soul” which the discipline of philosophy can enhance, even as religion

helps philosophy find its proper place in history. This “place” is none other

than the immediacy of the moment in which consciousness sees itself as a

gesture of nothingness within the world of being. For consciousness does

not see reality from without, but is an act of reality from within and there¬

fore part of it. This is the fountainhead of all personal goodness, all just soci¬

eties, all true art and philosophy and religion for Nishida.

Absolute Nothingness

Nishida s idea of absolute nothingness, which was later to be taken up and

developed by Tanabe and Nishitani each in his own way, is not a mere gloss

on his logic of locus. His descriptions of historical praxis as “embodying

absolute nothingness in time,” 9 and religious intuition as “penetrating into

the consciousness of absolute nothingness” 10 are intended to preserve the

experiential side of the logic and at the same time to assert a distinctive

metaphysical position. But at a more basic level, the idea of nothingness

itself is the stumbling block for philosophies which consider being as the

most all-encompassing qualification of the real, and which see nothingness

aS C ^ c * ass of everything excluded from reality.

n is search for the ultimate locus of self-awakening—the point at which

a lty recognizes itself, through the enlightened consciousness of the

man individual, as relative and finite—Nishida could not accept the idea

su P re me being of ultimate power and knowledge beside which all else

unb n ° , m ? re . C ^ an a P a ^ e analogy. He conceived of his absolute as an

k e - n ° Ur L,/“ circumstance rather than as an enhanced form of ordinary

had b C ^° CUS . being in reality could not itself be another being; it

was b° C SOmet ^ n £ that encompassed being and made it relative. Being

with one S a ^ 0rm c °dependency, a dialectic of identities at odds

other ^ ^ e ^ nin & one another by each setting itself up as non-

Only a p S t C t L° ta ^ t ^ suc h things, being could not be an absolute,

of f u _ ?j t . t e ^-embracing infinity of a nothingness could the totality

of Che world which beings m0 ve exist at all.

p-jon ; n ^^ s ^ lc ^ a ^cognized that “God is fundamental to reli-

rehVin 0rm ‘ ^is left him with two options: either to redefine what

r i ’ ! particularly Christianity, calls God as absolute nothingness; or

. I ° W e a ^ so ^ ute being is relative to something more truly

, 1S 1 a ° Un ^ a c bird way: he took both options. Nishida’s God

a so ute eing -in- absolute nothingness.” The copulative in here

meant to signal a relationship of affirmation-in-negation (the so-called

PHILOSOPHY AS SPIRITUALITY

373

logic of soku-hi which Nishida seems to owe more to D. T. Suzuki than to

the Buddhist sources on which Suzuki drew). The two terms are bound to

one another by definition. In the same way that there cannot be a creator

without creatures, or sentient beings without a Buddha, Nishida writes,

there cannot be an absolute being without an absolute nothingness. On the

one hand, he insists that the absolute is “truly absolute by being opposed

to absolutely nothing.” On the other, “the absolute is not merely non-

relative_It must relate to itself as a form of self-contradiction. 12

Even his clearest remarks in this regard are something of a logical tangle

and continue to perplex his commentators. 13 Insofar as I have been able to

understand the texts, Nishida’s reluctance to absorb God without remain¬

der into absolute nothingness seems to stem from his need to preserve the

element of pure experience in awakened selfhood. Metaphysically, he

refused to pronounce on God’s nature or existence. But “dropping off body

and mind to be united with the consciousness of absolute nothingness 14 is

also a religious act, and one that transforms perception to “see eternity in

the things of everyday life.” As such, it is an engagement of one’s truest,

deepest self with a radical, absolute otherness. Nishida recognized this basic

“spiritual fact” to be the cornerstone of religion, articulated in God-talk or

Amida-talk as nowhere else in philosophical history. In other words, if the

absolute in itself is “absolved’’ of all dependence on the relative, there is yet

a sense in which the absolute for us must be nearer to our true selves than

anything else can be. The very nature of absolute nothingness was bound to

this contradiction: “In every religion, in some sense, God is love. 15 It is also

the point at which logic must finally yield to experience, and hence where

Nishida’s perplexing prose can best be read as a philosopher’s bow to religion.

Clearly Nishida’s notion of absolute nothingness is different from the

“beyond being” ( eji'e/cEiva njs ovoia ?) of classical negative theology. If any¬

thing, his idea of locating nothingness absolutely out of this world of being

may be seen as a metaphysical equivalent of locating the gods in the heav¬

ens. His point was not to argue for an uncompromising transcendence of

ultimate reality, but to establish a ground for human efforts at self-control,

moral law, and social communion that will not cave in when the earth

shakes with great change or life is visited by great tragedy. True, the per¬

sonal dimension of the divine-human encounter (and its reflection in Chris-

tological imagery) is largely passed over in favor of an abstract notion of

divinity not so very different from the God of the philosophers that Pascal

rejected. In general, Nishida alludes to God as an idiom for life and cre¬

ativity minus the connotations of providence and subjectivity. But for one

so steeped in the Zen Buddhist perspective as Nishida to have given God

374

JAPAN

such a prominent place in his thought proved to be a decisive ingredient in

opening Kyoto-school philosophy to the world.

On the whole, Nishida’s “orientalism” is restrained to an ancillary role in

his philosophy. Zealous disciples, less secure in their philosophical vocation

and lacking Nishida s religious motivation, have been preoccupied with

finding in him a logic of the East distinct from that of the West. Nishida

himself did not go so far. Rarely, if ever, does he set himself or his ideas up

as alternative or even corrective to “Western philosophy” as a whole. He

was making a contribution to world philosophy and was happy to find affil¬

iates and sympathetic ideas, hidden or overt, in philosophy as he knew it.'

That said, his attempts to return the true self awakened to absolute noth¬

ingness to the world of historical praxis rarely touch down on solid ground.

Even the most obvious progression from family to tribe to nation to world

is given little attention. In principle he would hardly have rejected such an

expansion of the self (though it must be said that during the war years, he

came dangerously close to describing Japanese culture as a kind of self-

enc osed world with the emperor as the seal of its internal identity). But this

was not his primary focus, and in fact he never found a way to apply his

search for the ultimate locus of the self to the pressing moral demands of

The bulk of his reflections on the historical world concerns general,

uctures of human acting and knowing in time rather than the relation of

p cu ar nations and cultures to universal world order. The attainment of

true self ultimately lies beyond history; it happens in the “eternal now.”

■ [ C most ^ mrne diate existential fact of the I-Thou relationship is

„ . , Ce . virtuall y w khout ethical content into the abstract logic of the

entity of opposites in which the I discovers the Thou at the bottom

own interiority. These questions provided the starting point for the

contributions of Nishitani and Tanabe.

Tanabe Hajime: Locating Absolute Nothingness in Historical Praxis

any of the young intelligentsia of his generation, Tanabe was attract-

C Trr ^ an< ^ ori S inalit y of Nishida’s thinking. But his was a tem-

perament 1 erent from Nishida's. His writings show a more topical flow

o ideas and a passion for consistency that contrasts sharply with Nishida’s

tive eaps o imagination. If Nishida’s prose is a seedbed of suggestive¬

ness w lere one needs to read a great deal and occasionally wander off

etween t e ines to see where things are going, Tanabe’s is more like a

mathematical calculus where the surface is complex but transparent. Nishi-

a s wor , it has been said, is like a single essay, interrupted as often by the

PHILOSOPHY AS SPIRITUALITY

375

convention of publishing limits or deadlines as by the end of a thesis. One

problem flows into the next, not in the interests of a unified system of

thought but in pursuit of clarity about the matter at hand. Tanabe—and

for that matter, Nishitani also—were more thematic and produced essays

that can stand on their own and be understood as such.

When Meiji Japan opened its doors to the world in the mid-nineteenth

century after two hundred years of cloister, it immediately-inherited intel¬

lectual fashions that had been nurtured during the European enlighten¬

ment and the explosion of modern science. Not having been part of the

process, Japan was ill-prepared to appropriate its results critically. That the

road should have been a bumpy one, very different both from the West and

from its Asian neighbors, is understandable. As Japan was going through

its restoration to the community of nations, the countries of Europe were

struggling with the idea of national identity. National flags, songs, and

other more ritual elements aside, we find for the first time a widespread

concern with distinctive national literatures and philosophies, along with

national psychologies. The human sciences, all in their infancy, were caught

up in this fascination even as they tried to monitor it. While the cosmopol¬

itan spirit of the enlightenment struggled to survive this test of its roots,

the natural sciences and technology proudly marched in the van of a

transnational, transcultural humanity. Throughout it all, Japan swayed

back and forth between a total infatuation with the superior advances of

Western culture and a rigid determination to carve out for itself a unique

position in the world.

Nishida suffered this ambiguity as a man of his age. 'While he never

sought translation of his thought into foreign languages, he did recognize

the need for ties with the contemporary world of philosophical thinkers. To

this end, Tanabe was sent by Nishida to study in Europe, where word of

Nishida’s work had already stirred interest. Whereas Nishida could calmly

pen German phrases here and there in his diaries and skim through English

and French books without the fear of criticism at home, the young Tanabe

had to struggle with the daily life of a foreigner clumsily making his way in

a tongue and culture he had so far only admired from a distance. In the

course of time, a certain resentment seems to have built up in him over

Nishida’s insistence that he pursue neo-Kantian thought. His own interests

turned him in the direction of phenomenology, but on returning to Japan

he was met with a request of Nishida for a major paper on Kant for a col¬

lection celebrating the two hundredth anniversary of the latter s death. Its

composition was a turning point for Tanabe.

In his essay Tanabe argued that Kant’s third Critique lacked an important

376

JAPAN

ingredient that Nishida s philosophy could supply. Specifically, he tried to

wed the idea of self-awakening to Kant’s practical reason in order to shift

the foundations of morality away from a universal moral will in the direc¬

tion of absolute nothingness. On the one hand, he saw that awareness of

nothingness could provide moral judgment with a telos outside of subjec¬

tive will. This “finality of self-awareness,” as he termed it, could provide “a

common principle for weaving history, religion, and morality into an insol¬

uble relationship with one another. On the other hand, it dawned on him

that Nishida’s true, awakened self effectively cut the individual off from

history. On completion of his essay, he turned to Hegel to fill the gap. In

time he realized that Hegel’s absolute knowledge was lacking content, and

he set out to think through the possibility of praxis in the historical world

grounded in the self-awareness of absolute nothingness. Nishida, for his

part, was hard at work on his logic of locus, but Tanabe was not persuaded

t at it would solve his problem. During this period he developed his dialec-

c of absolute mediation as a way of establishing the bond between

absolute nothingness and the historical world . 16

hilosophical questions aside, two things should be noted with regard to

I e ^ attem pts to draw the philosophical vocation closer to the histori-

xj. , .^ r * ^ rst °f a ll, the tendency to be abstract that Tanabe criticized in

rec a Ver ^ muc ^ ^is own problem. In fact, on his own account he

ness^^ ^ aw * n m y speculative powers” as responsible for his abstract-

no y ; Tanabe S & en * us > as apparent as it was to his students, was

took an C ° r C e overwhelming presence of Nishida, towards whom he

i t y er more critical position even as he continued to measure his own

qnnr?l° P ^ pr °£ ress as a Japanese working primarily with Western

, h S agam ^ Nlshida ’ s contributions. As Nishitani recalls, the dialectic

j i S a van ^ ln g seems to give us a mirror-image of Tanabe himself

e y struggling to escape the embrace of Nishida’s philosophy .” 18

Absolute Nothingness and the Logic of the Specific

On the occasion of Nishida’s retirement, when the academic world was pil-

I r eS ° n * ts ^ rst and greatest world philosopher, Tanabe wrote a

xj- i -i g l plGC j e devious ly entitled “Looking Up to Nishida.” Leaving

tv’ TT t0 1S . °^ C l ocus > Tanabe (who now held Nishida’s chair at

yoto niversity) prepared the way for his own “logic of the specific” by

p esting t at the religious experience that goes by the name of the ‘self-

a ening o a solute nothingness ... belongs outside the practice and

anguage o p i osophy, which cannot put up with such a complete lack of

PHILOSOPHY AS SPIRITUALITY

377

conceptual definition.... Religious self-awareness must not be set up as the

ultimate principle of philosophy .” 19

The religious bent in Nishida’s philosophy was fed by his many years of

sitting in zazeii and his ongoing contact with Buddhist and Christian

thinkers. Tanabe’s religiosity was more bookish. No less than Nishida, he

shied away from turning the philosopher’s trade against organized religion

and tried to get to the heart of religious and theological thinkers, but his

religiosity was a more solitary one. No diaries and few letters remain to let

us suppose otherwise. The irony is that Tanabe is remembered as the more

religious figure because of a postwar book on penitential philosophy in

which he criticizes the profession he had devoted his life to, himself includ¬

ed, for its moral timidity.

Tanabe’s contribution to Kyoto-school philosophy as a religious way, as I

have said, cannot be separated from his uneasy relationship with Nishida,

which stimulated him to look closely at some of the questions Nishida had

skimmed over in his creative flights and which also gave him the founda¬

tions for doing so. From Nishida he received the idea of approaching reli¬

gious judgments in terms of affirmation-in-negation, as well as the convic¬

tion of absolute nothingness as the supreme principle of philosophy. Fur¬

ther, like Nishida, he did not consider anything in Japanese language or

thought a final measure of what was most important in his philosophy.

These attitudes he passed on, passionately, to the students. Finally, like

Nishida he never argued for the supremacy of any one religious way over

any other. What he did not take from Nishida, however, was a conviction

of the primacy of religious experience as an “event of the soul which phi¬

losophy may or may not try to explain but can never generate. For Tanabe,

there is no unmediated religious experience. Either it is appropriated by the

individual in an “existentially philosophic” manner or it yields to the

specificity of theology, ecclesial institution, or folk belief . 20

Tanabe’s search for his own philosophical position began with a meticu¬

lous rethinking of Hegel’s dialectic as applied to a philosophy of absolute

nothingness. Along the way he became convinced that for nothingness to be

absolute, it was not enough for it to serve as a principle of identity for the

finite world from a position somewhere outside of being. It must be a dyna¬

mic force that sustains the relationships in which all things live and move

and have their being. He could not accept the idea that the historical world

in which opposites struggle with one another to secure their individual

identities is being driven inexorably towards some quiet, harmonious, beatific

vision in absolute mind; neither could he feel at home in the private awaken¬

ing to a true self within. Precisely because all things without exception are

34. Nishida Kitaro, age 46 (1916).

PHILOSOPHY AS SPIRITUALITY

379

made to struggle with one another for their individuality, the dialectic is an

absolute fact of being cannot be accounted for within the world of being

alone. Only a nothingness outside of being can make things be the essen¬

tially interactive things that they are. But the reverse is also true: “Insofar

as nothingness is nothingness, it is incapable of functioning on its own.

Being can function only because it is not nothingness .” 21

If nothingness allows the world to be, awakening to this fact serves as a

permanent critical principle in all identity, whether in the sense of a lofty

philosophical principle like Nishida’s self-identity of absolute contradicto¬

ries or in the sense of the ordinary psychological self-composure of the indi¬

vidual mind. It is the fire in which all identity is purged of the fictions of

individuality and substantiality that mind attaches to it, leaving only the

pure awakening to that which has itself no conflict, no otherness: nothing¬

ness. This purification of the mind was Tanabe’s test of religious truth. In

its terms he appreciated the great figures of the Buddhist and Christian

religious past.

The logic of the specific is testimony to the fact that Tanabe never made

peace with his own tendency to distance himself from the historical world

in the way Nishida did. Many of the latter’s young disciples had turned the

sharp analysis of Marxism against Nishida’s fixation on self-awareness, but

to little avail. Tanabe, in contrast, from his critical reading of Kant, had

come to see that the subject of consciousness is not a mere individual who

looks at the world through lenses crafted by nature for the mind without

consultation. It is also a by-product of specific cultural, ethnic, and epochal

conditions. In its purgative function, the awareness of absolute nothingness

demands that even our most treasured theories be seen as bundles of rela¬

tionships not within our control. We cannot speak without a specific lan¬

guage nor think without circumstances with a history. We are not individ¬

uals awakening to universal truths, but stand forever on specificity, a great

shifting bog of bias and unconscious desire beyond the capacity of our mind

to conquer once and for all. Nothingness sets us in the mire, but it moves

us to struggle against it—never to be identified with it, never to assume we

have found an identity of absolute contradictories that is not contaminated

by specificities of history. This “absolute negation” is the goal of religion . 22

Philosophical Metanoia

The problem for Tanabe was to salvage a meaning for self-awakening in this

logic of the specific and not resign oneself to the cunning of history. It was

not a lesson he taught himself in the abstract but rather one that was forced

380

JAPAN

on him by his own injudicious—and probably also unnecessary—support of

state ideology at the height of Japan’s military escapades in Asia. The logic

that he had shaped to expose the irrational element in social existence was

now used to set up against the “clear-thinking gaze of existential philoso¬

phy” something more engaging: the “praxis of blessed martyrdom” in a

“war of love.” Proclaiming the nation as the equivalent of Sakyamuni and that

“participation in its life should be likened to the imitatio Christi ,” 23 Tanabe

lost touch with the original purpose of his logic of the specific.

While these sentiments frothed at the surface of Tanabe’s prose, a deep

resentment towards the impotence of his own religious philosophy seethed

within him, until in the end it exploded in the pages of his classic work Phil¬

osophy as Metanoetics. It was no longer enough to posit absolute nothingness

as a supreme metaphysical principle grounding the world of being. It must

be embraced, in an act of unconditional trust, as a force liberating the self

from its native instinct to self-sufficiency. The notion of faith in Other-

Power as expressed in the Kyogyoshinsho of Shinran (1 173—1262) gave Tanabe

the basic framework for his radical metanoia and reconstruction of a phil¬

osophy from the ground up.

It is no coincidence that the heaviest brunt of his penitential attack on

overreliance on the power of reason fell on the head of Kant’s transcendental

philosophy, but from there it reaches out to a reassessment of virtually all

his major philosophical influences, from Hegel and Schelling to Nietzsche,

Kierkegaard, and Heidegger. Woven into this critique is a positive and

unabashedly religious insistence on what he calls “nothingness-in-love” or

compassionate praxis in the historical world. The principal model for this

ideal is the Dharmakara myth of ascent-in-descent in which the enlight¬

ened bodhisattva returns to the world in order to certify his own awakening,

but frequent mention is also made of the Christian archetype of life-in-death,

which was to dominate certain of his later works. 24 In any case, his aim was

not to promote any particular religious tradition over any other but to bridge

the gap between absolute nothingness and concrete reality in a way that a

simple leap of self-awareness could not accomplish. He drew on religious

imagery because it seemed to keep him focused on the moral obligation of

putting the truth of enlightened mind to work for the sake of all that lives.

As it turned out, the purgative, “disruptive” side of his metanoetics over¬

shadowed the practical, moral side and left him on shaky ground when it

came to taking his new “philosophy that is not a philosophy” beyond its ini¬

tial statement. Tanabe was aware of this, and devoted his late years to rein¬

forcing the foundations of his logic of the specific, fusing elements from

Zen, Christianity, and Pure Land in the forge of a loving, compassionate

PHILOSOPHY AS SPIRITUALITY

381

self-awakening. But when all was said and done, Tanabe, like Nishida,

remained aloof from the concrete problems of science, technology, economic

injustice, and international strife that were shaking the foundations of the

historical world outside the walls of his study. His was to the end a philos¬

ophy committed to uncluttering the mind of its self-deceptions, but forever

haunted by the knowledge that only in the hopelessly cluttered specificity

of history can moral praxis exert itself. The vision he left us is a portrait of

his own struggles with the intellectual life: a seamless robe of ideals tattered

by experience but not rent, whose weave remains a testimony to the

weaver’s dedication to the philosophical vocation as a spiritual way.

Nishitani Keiji: From Nihility to Nothingness

With Nishitani, the philosophical current that flowed from Nishida

through Tanabe spread out in fresh, new tributaries. Not only did he carry

over Tanabe’s concern with historical praxis; he also drew the ties to Bud¬

dhism closer than either of his senior colleagues had done and closer, as

well, to the lived experience of the philosophical quest. In addition, Nishi¬

tani took up in his philosophy two major historical problems, each pulling

him in a different direction. He was preoccupied, on the one hand, with fac¬

ing the challenge that modern science brought to religious thinking; on the

other, with establishing a place for Japan in the world. All of this combines

to give his writing a wider access to the world forum.

More than Nishida and Tanabe, Nishitani turned his thought on a world

axis. He actively welcomed and encouraged contact with philosophers from

abroad, and in his final years many a foreign scholar beat a path to his small

home in Kyoto. 25 He, too, studied in Germany as Tanabe before him, and

later was to travel to Europe and the United States to lecture. The happy

combination of the publication of his major work, Religion and Nothingness,

in English and German translation, the rising number of Western scholars

with the skills to read fluently in the original texts, and the great human

charm of Nishitani as a person, helped bring the work of the Kyoto philoso¬

phers to a wider audience. Still, given the trends in Continental and Amer¬

ican philosophy at the time this was happening, it was unsurprising that it

was the theologians and Buddhologists who were most attracted to Nishi-

tani’s work. Only after his death did neighboring Asian countries like

Korea, Taiwan, and Hong Kong begin to show an interest in him and other

of the Kyoto-school philosophers. But for all his cosmopolitan sentiments,

Nishitani followed, his predecessors in showing favoritism towards the

West—as had virtually all Japanese philosophers since the Meiji period.

382

JAPAN

In defending himself against the Inquisition, Galileo presented what has

become the central assumption of modern science. “I am not interested,” he

said, "in how to go to heaven, but in how the heavens go.” This dichotomy

was one that Nishitani never accepted. Not only had the West got it wrong

in separating philosophy from religion, its separation of religious quest

from tne pursuit of science also seemed to him fundamentally flawed. Any¬

thing that touches human existence, he insisted, had its religious dimen¬

sion. Science is always and ever a human enterprise in the service of some¬

thing more, but when the existential element is sacrificed to the quest for

scientific certitude, what we call life, soul, and spirit—including God—

find their home destroyed. Nishitani’s response was not to retreat into

preoccupation with the true self, but to argue that only on the self’s true

homeground do the concrete facts of nature "manifest themselves as they

are, in their greater ‘truth’.” 26

In Nishitani the concern with true self reaches its highest point in Kyoto

p ilosophy. He saw this as the focal point of Nishida’s work and interpreted

anabe s philosophy as a variation on that theme. In his own writings he

rew to the surface, through textual allusions and direct confrontation with

t e original texts, many of the Zen and Buddhist elements in Nishida’s

^ VOr ‘ ^ Suzuki s efforts to broaden Zen through contact with Pure

an Buddhism also reverberate in Nishitani’s writings, though not as

cep y as they do in Tanabe s. In addition, he turned directly to Christian

t eo ogy both for inspiration and to clarify his own position as distinct from

the Christian one.

P er ^ a P s the single greatest stimulus to Nishitani’s broadening of

ishidas philosophical perspective was Nietzsche, whose writings were

never far from his mind. The deep impression that Thus Spoke Zarathustra

a made on him in his university years left him with doubts so profound

at, in the end, only a combination of Nishida’s method and the study of

en Buddhism was able to keep them from disabling him. As a scholar of

[ osophy he had translated and commented on Plotinus, Aristotle,

oe me Descartes, Schelling, Hegel, Bergson, and Kierkegaard—all of

w °m e t their mark on his thought. But Nietzsche, like Eckhart, Dogen,

^ \ an ' ^^-te, ^ en P oets > and the New Testament, he seems to have

rea t rough the lenses of his own abiding spiritual questions, resulting in

rca mgs of arresting power and freshness.

The fundamentals of Nishitani’s own approach to the true self as a philo¬

sophical idea are set forth in an early book on "elemental subjectivity.” This

term (which he introduced into Japanese from Kierkegaard) is not one that

Nishida favored, but Nishitani’s aim is not substantially different from that

PHILOSOPHY AS SPIRITUALITY

383

of his teacher: to lay the philosophical foundation for full and valid indi¬

vidual existence, which in turn would be the basis for social existence, cul¬

tural advance, and overcoming the excesses of the modern age. Written at

the age of forty and under the strong influence of Nishida, the work con¬

tains in germ his own mature philosophy.

As with Nishida, the Achilles’ heel of Nishitani’s highly individual

approach to historical questions was its application to questions of world

history. In the attempt to lend support during the war years to elements in

the Navy and government who wanted to bring some sobriety to the mind¬

less antics of the Japanese Army in Asia, his remarks on the role of Japan¬

ese culture in Asia blended all too easily with the worst ideologies of the

period, and the subtle distinctions that made all the difference to him as

they did to Nishida and Tanabe caught up in the same maelstrom earn

him little sympathy today in the light of subsequent events. Nishitani suf¬

fered a purge after the defeat of Japan and never returned to these ques¬

tions in print. While he continued to write on Japan and the culture of the

East, he did so at a safe distance both from his own earlier opinions and

from the relentless pummeling of Marxist critics.

The Standpoint of Emptiness

To Nishida’s logic of locus and Tanabe’s logic of the specific, Nishitani

added what he called the standpoint of emptiness. He saw this standpoint

not as a perspective that one can step into effortlessly, but the achievement

of a disciplined and uncompromising encounter with doubt. The long

struggle with nihilism that lay behind him was far from merely academic.

As a young man, not yet twenty years of age, he had fallen into a deep

despair in which “the decision to study philosophy was, melodramatic as it

might sound, a matter of life and death for me.” 27 This was to be the very

starting point for his description of the religious quest: We become aware

of religion as a need, as a must for life, only at the level of life at which every¬

thing else loses its necessity and its utility.” 28

For Nishitani, the senseless, perverse, and tragic side of life is an unde¬

niable fact. But it is more than mere fact; it is the seed of religious aware¬

ness. The meaning of life is thrown into question initially not by sitting

down to think about it but by being caught up in events outside one s con¬

trol. Typically, we face these doubts by retreating to one of the available

consolations—rational, religious, or otherwise—that all societies provide to

protect their collective sanity. The first step into radical doubt is to allow

oneself to be so filled with anxiety that even the simplest frustration can

384

JAPAN

reveal itself as a symptom of the radical meaninglessness at the heart of all

human existence. Next, one realizes that this sense of ultimate is still

human-centered and hence incomplete. Now one gives oneself over to the

cfoubt entirely, and the tragedy of human existence shows itself as a symp¬

tom of the whole world of being and becoming. At this point, Nishitani

says, it is as if a great chasm had opened up underfoot in the midst of ordi¬

nary life, an "abyss of nihility.”

Whole philosophies have been constructed on the basis of this nihility,

and Nishitani threw himself heart and soul into the study of them, not in

order to reject them but in order to find the key to what he called the "self¬

overcoming of nihilism. The awareness of nihility must be allowed to grow

in consciousness until all of life is transformed into a great question mark.

Only in this supreme act of negating the meaning of existence so radically

that one becomes the negation and is consumed by it, can the possibility of

a breakthrough appear. Deliverance from doubt that simply transports one

out of the abyss of meaninglessness and back into a worldview where things

make sense again, Nishitani protests, is no deliverance at all. The nihility

itself, in the fullness of its negation, has to be faced squarely in order to be

seen through as relative to human consciousness and experience. In this

rmation, reality discloses its secret of absolute emptiness that restores

II in his philosophical terms, “emptiness might be

ca ed the field of ‘be-ification (lebtung) in contrast to nihility, which is the

neld of nullification’ (Nichtung ).” 29

her words, for Nishitani religion is not so much a search for the

te as one of the items that make up existence, as an acceptance of the

P "ss t at embraces this entire world of being and becoming. In that

acceptance—a "full-bodied appropriation” (tainin )—mind lights up as

ng t y as mind can. The reality that is lived and died by all things that

e an P ass awa Y in the world is realized” in the full sense of the

one s lares in reality and one knows that one is real. This is the stand¬

point of emptiness.

use it is a standpoint, it is not a terminus ad quern so much as a ter-

quo. t e inauguration of a new way of looking at the things of life,

new way of valuing the world and reconstructing it. All of life becomes,

he says a kind of “double-exposure” in which one can see things just as they

re an at the same time see through them to their relativity and tran¬

sience. Far from dulling one’s critical senses, it reinforces them. To return to

t ie case of science, from the standpoint of emptiness, the modern infatua¬

tion with explanation and fact is disclosed for what it is: a sanctification of

the imperial ego that willingly sacrifices the immediate reality of its own

PHILOSOPHY AS SPIRITUALITY

385

true self for the illusion of perfect knowledge and control. To personify or

humanize the absolute, to rein it in dogmatically with even the most

advanced apparatus and reliable theories, is at best a temporary cure to the

perpetual danger of being overwhelmed by nihility. Only a mysticism of the

everyday, a living-in-dying, can attune our existence to the empty texture

of the absolutely real.

In general, it may be noted, Nishitani favored the term emptiness (S. suny-

ata) over Nishida’s “absolute nothingness,” in part because its correspon¬

ding Chinese glyph, the ordinary character for sky, captures the ambiguity

of an emptiness-in-fullness that he intends. In this seeing that is at the same

time a seeing-through, one is delivered from the centripetal egoity of the

self to the centrifugal ex-stasis of the self that is not a self. This, for him, is

the essence of religious conversion.

In principle, Nishitani always insisted that conversion entails engage¬

ment in history. While he appreciated, and often repeated, the Zen Bud¬

dhist correlation of great doubt with great compassion (the Chinese glyphs

for both terms are pronounced the same, daihi ), his late writings contain

numerous censures of Buddhism for its “other-worldly refusal to enter into

the affairs of human society,” for its “lack of ethics and historical conscious¬

ness,” and for its “failure to confront science and technology.’ 30

In his principal philosophical discussions of history, however, Nishitani

tends to present Christian views of history, both linear and cyclical, as a

counterposition to the fuller Buddhist-inspired standpoint of emptiness

despite the greater sensitivity of the former to moral questions. Emptiness

or nothingness did not become full by bending time back on itself periodi¬

cally, like the seasons that repeat each year, or by providing an evolutionary

principle that points to an end of time when all the frustrations of nihility will

be overturned, as is the case in Christian eschatology. He envisaged deliv¬

erance from time as a kind of tangent that touches the circle of repetitive

time at its outer circumference or cuts across the straight line of its forward

progress. Like Nishida, he preferred the image of an “eternal now that

breaks through both myths of time to the timelessness of the moment of

self-awakening. What Christian theism, especially in its personalized image

of God, gains at one moment in its power to judge history, it often loses at

the next in its failure to understand the omnipresence of the absolute in all

things. For Nishitani the standpoint of emptiness perfects the personal

dimension of human life by the addition of the impersonal, non-differenti¬

ating love, which was none other than the very thing that Christianity

reveres in the God who makes the sun to shine on the just and the unjust

alike, and who empties himself kenotically in Christ. 31 Yet here again, we

386

JAPAN

see Nishitani in later writings reappraising the I-Thou relationship and the

interconnectedness of all things, even to the point of claiming that “the per¬

sonal is the basic form of existence.

I*n the foregoing pages much has been sacrificed to brevity and a certain

forced clarity of exposition. Perhaps only the askese of struggling with the

original texts can give one a sense of the complexity of the Kyoto school

thinkers. Philosophically, many problems remain with the “logics” of Nishi¬

da, Tanabe, and Nishitani. Some of them have been superseded by more

recent philosophy; others will benefit from further study and comparison;

still others are perennial. The task of formulating philosophical questions as

religious ones belongs, 1 am convinced, among the latter.

Notes

1. Karl Jaspers, The Way to Wisdom (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1954),

14. Translation adjusted.

2. These two ideas are present from Nishida’s earliest writings. See his two brief

essays on Bergson in Nishida Kitaro zenshu (hereafter NKZ) 1:317-27; The idea of

appropnarion (jitoku) appears in An Inquiry into the Good , 5 1 (where it is trans-

ated realizing with our whole being").

3. Nishitani, Nishida Kitaro , 55.

n• °f the No Drama: The Major Treatises of Zeami , trans. by J. Thomas

i *T CI ^x Yamazaki Masakazu (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984),

1 35 , 136 .

5. This term is sometimes translated as "logic of topes," but the connections to

nstotle which the term suggests seem to conflict with his own position,

o. bee Kosaka Masaaki chosakushu 8:98-101.

8 2L KZ see Inquiry into the Good , 49.

has V* W'itin&y 34. In order to capture the philosophical sense, the translator

a C , n , S °I? e llbertics w kh particular passages. A more literal translation was

81-no by YuSa Michiko in The Eastern Buddhist 19:2 (1986) 1-29, 20/1 (1987)

\j -T eX ' Ual re ^ crcnces to this idea may be found in Jacinto, La filosofia social de

Nishida Kitaro, 208—12

10. NKZ 5:182.

11. Last Writings , 48.

12. Last Writings, 68—69.

ichi 3 T d hC Al° ng " Standin8 debates amon £ Takizawa Katsumi, Abe Masao, Yagi Sei-

l an |zuki Ryomin over the reversibility or irreversibility of the relationship

... ween °d and the self,-as well as the wider debate over the obscure notion of

. m y erSe c ° rres pondence (gyakutaio) that appears in Nishida’s final essay, leave lit¬

tle hope of a final word on the subject.

, • 5:177 * The allusion, of course, is to Dogen’s Genjokoan.

15. NKZ 11:372, 454, 435.

PHILOSOPHY AS SPIRITUALITY

387

16. Tanabe Hajime zenshu (hereafter THZ) 3:7, 78—81.

17. THZ 3:76-77.

18. Nishitani, Nish id a Kitard , 167.

19. THZ 4:306, 318.

20. THZ 8:257-38.

21. THZ 7:261.

22. THZ 6:147-53.

23. THZ 7:24, 99.

24. Regarding his relation to Christianity, Tanabe referred to himself in 1948 as

a permanent Christian-in-the-making, ein werdender Christ who could never

become ein gewordener Christ (THZ 10:260). The distinction is more commonly

associated with Nishitani, who adopted it to describe his own sympathies with

Tanabe’s position.

25. See the special issue of The Eastern Buddhist devoted to the memory of Nishi¬

tani, 25:1 (1992).

26. “Science and Zen,” The Buddha Eye , 120, 126.

27. Nishitani Keiji chosakushu (hereafter NKC) 20:175—84.

28. Religion and Nothingness , 3-

29- Religion and Nothingness , 124.

30. See NKC 17:141, 148-50, 154-55, 230-31.

31. See especially Religion and Nothingness , ch. 2.

32. NKC 24:109.

Bibliography

Primary Sources

Franck, Frederick, ed. The Buddha Eye: An Anthology of the Kyoto School. New York.

Crossroad, 1982.

Jacinto Zavala, Agustin, ed. Textos de la filosofia japonesa rnodema (Zamora: El Cole-

gio de Michoacan, 1995), vol. 1.

Nishida Kitard zenshu (Collected works of Nishida Kitaro). 19 vols. Tokyo: Iwa-

nami, 1978.

Nishida Kitaro. An Inquiry into the Good. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1990.

--. Last Writings: Nothingness and the Religious Worldview, trans. by David Dil-

worth. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1987.

Nishitani Keiji chosakushu (Collected works of Nishitani Keiji). Tokyo: Sobunsha,

1986-. 26 vols: to date.

Nishitani Keiji. Religion and Nothingness. Berkeley: University of California Press,

1982.

-. The Self-overcoming of Nihilism. Albany: State University of New York

Press, 1990.

Ohashi Ryosuke, ed. Die Philosophic der Kyoto-Schule: Texte und Einfiihrung.

Freiburg: Karl Alber, 1990.

Tanabe Hajime zenshu (Collected works of Tanabe Hajime). 15 vols. Tokyo: Chiku-

ma Shobo, 1964.

Tanabe Hajime. Philosophy as Metanoetics. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1986.

388

JAPAN

Secondary Sources

Heisig James W, and John Maraldo, eds. Rude Awakenings: Zen, the Kyoto School

, ■ a ” d !l 3e Q“ estlon of Nationalism. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 1994-

lacmm 7™<,lo 1 1935-1945- &

j ~ ^ jonn M ar aJdo, cds. Rude Awaken mgs:

larinrn 7 Q !/est 'on of Nationalism. Honolulu: University of Hav

J I ZlV ri r Agustin, ed. U filosofia social cle Nishula Kitaru,

mo a: El Coleg.o de Michoacan, 1995 vol 1

Kosaka Masaaki chosaktishii. Tokyo: Risoshaj 1965 vol 8

Unno 6 ’w neS ' D \ al Ti l ‘ k der absol, “ en Vemnttlung. Freiburg: Herder, 1984.

Ph,losophy ofLhita,,i Ke,ji - Derke,ey:

_ Un T;y T XTa S n U Hu n manides Pre^^O^’ ^ Phihs ^ ^

Nl thf£w2y Ta r n pA7 Ha | ime> '' “ Nlshltan ' Keiji," and "The Kyoto School" >"

N ishida Ki^r^^M^or^a/I^sue^ 77 °^^ 0 ' ^

Nishitani Kciii • i r UC ' ^ astern Buddhist 28:2 (1995).

ei, ‘ Mem0r,al Iss ^- The Eastern Buddhist 25:1 (1992).