Transcendentalism

| Part of a series on |

| Spirituality |

|---|

| Outline |

| Influences |

| Research |

Transcendentalism is a philosophical movement that developed in the late 1820s and 1830s in New England.[1][2][3]

A core belief is in the inherent goodness of people and nature,[1] and while society and its institutions have corrupted the purity of the individual, people are at their best when truly "self-reliant" and independent.

Transcendentalists saw divine experience inherent in the everyday, rather than believing in a distant heaven.

Transcendentalists saw physical and spiritual phenomena as part of dynamic processes rather than discrete entities.

Transcendentalism emphasizes subjective intuition over objective empiricism. Adherents believe that individuals are capable of generating completely original insights with little attention and deference to past masters. It arose as a reaction, to protest against the general state of intellectualism and spirituality at the time.[4] The doctrine of the Unitarian church as taught at Harvard Divinity School was closely related.

Transcendentalism emerged from

- "English and German Romanticism, the Biblical criticism of Johann Gottfried Herder and Friedrich Schleiermacher,

- the skepticism of David Hume",[1] and

- the transcendental philosophy of Immanuel Kant and German idealism.

- Perry Miller and Arthur Versluis regard Emanuel Swedenborg and Jakob Böhme as pervasive influences on transcendentalism.[5][6]

- It was also strongly influenced by Hindu texts on philosophy of the mind and spirituality, especially the Upanishads.

Origin[edit]

Transcendentalism is closely related to Unitarianism, the dominant religious movement in Boston in the early nineteenth century. It started to develop after Unitarianism took hold at Harvard University, following the elections of Henry Ware as the Hollis Professor of Divinity in 1805 and of John Thornton Kirkland as President in 1810. Transcendentalism was not a rejection of Unitarianism; rather, it developed as an organic consequence of the Unitarian emphasis on free conscience and the value of intellectual reason. The transcendentalists were not content with the sobriety, mildness, and calm rationalism of Unitarianism. Instead, they longed for a more intense spiritual experience. Thus, transcendentalism was not born as a counter-movement to Unitarianism, but as a parallel movement to the very ideas introduced by the Unitarians.[7]

Transcendental Club[edit]

Transcendentalism became a coherent movement and a sacred organization with the founding of the Transcendental Club in Cambridge, Massachusetts, on September 12, 1836, by prominent New England intellectuals, including George Putnam (Unitarian minister),[8] Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Frederic Henry Hedge. Other members of the club included Amos Bronson Alcott, Orestes Brownson, Theodore Parker, Henry David Thoreau, William Henry Channing, James Freeman Clarke, Christopher Pearse Cranch, Convers Francis, Sylvester Judd, and Jones Very. Female members included Sophia Ripley, Margaret Fuller, Elizabeth Peabody, Ellen Sturgis Hooper, and Caroline Sturgis Tappan. From 1840, the group frequently published in their journal The Dial, along with other venues.

Second wave of transcendentalists[edit]

By the late 1840s, Emerson believed that the movement was dying out, and even more so after the death of Margaret Fuller in 1850. "All that can be said", Emerson wrote, "is that she represents an interesting hour and group in American cultivation".[9] There was, however, a second wave of transcendentalists later in the 19th century, including Moncure Conway, Octavius Brooks Frothingham, Samuel Longfellow and Franklin Benjamin Sanborn.[10] Notably, the transcendence of the spirit, most often evoked by the poet's prosaic voice, is said to endow in the reader a sense of purpose. This is the underlying theme in the majority of transcendentalist essays and papers—all of which are centered on subjects which assert a love for individual expression.[11] The group was mostly made up of struggling aesthetes, the wealthiest among them being Samuel Gray Ward, who, after a few contributions to The Dial, focused on his banking career.[12]

Beliefs[edit]

Transcendentalists are strong believers in the power of the individual. It is primarily concerned with personal freedom. Their beliefs are closely linked with those of the Romantics, but differ by an attempt to embrace or, at least, to not oppose the empiricism of science.

Transcendental knowledge[edit]

Transcendentalists desire to ground their religion and philosophy in principles based upon the German Romanticism of Johann Gottfried Herder and Friedrich Schleiermacher. Transcendentalism merged "English and German Romanticism, the Biblical criticism of Herder and Schleiermacher, the skepticism of Hume",[1] and the transcendental philosophy of Immanuel Kant (and of German idealism more generally), interpreting Kant's a priori categories as a priori knowledge.

Early transcendentalists were largely unacquainted with German philosophy in the original and

relied primarily on the writings of Thomas Carlyle, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Victor Cousin, Germaine de Staël, and other English and French commentators for their knowledge of it.

The transcendental movement can be described as an American outgrowth of English Romanticism.[citation needed]

Individualism[edit]

Transcendentalists believe that society and its institutions—particularly organized religion and political parties—corrupt the purity of the individual.[13] They have faith that people are at their best when truly self-reliant and independent. It is only from such real individuals that true community can form.

Even with this necessary individuality, transcendentalists also believe that all people are outlets for the "Over-Soul". Because the Over-Soul is one, this unites all people as one being.[14][need quotation to verify] Emerson alludes to this concept in the introduction of the American Scholar address, "that there is One Man, - present to all particular men only partially, or through one faculty; and that you must take the whole society to find the whole man".[15] Such an ideal is in harmony with Transcendentalist individualism, as each person is empowered to behold within him or herself a piece of the divine Over-Soul.

In recent years there has been a distinction made between individuality and individualism. Both advocate the unique capacity of the individual. Yet individualism is decidedly anti-government, whereas individuality sees all facets of society necessary, or at least acceptable for the development of the true individualistic person. Whether the Transcendentalists believed in individualism or individuality remains to be determined. Whitman embraced all facets of life, which seems more like individuality, which is more in tune with what the Indian spiritual tradition advocates; i.e. the True Individual, the yogic attainment of true individuality.

Indian religions[edit]

While firmly rooted in the western philosophical traditions of Platonism, Neoplatonism, and German idealism, Transcendentalism was also directly influenced by Indian religions.[16][17][note 1] Thoreau in Walden spoke of the Transcendentalists' debt to Indian religions directly:

In 1844, the first English translation of the Lotus Sutra was included in The Dial, a publication of the New England Transcendentalists, translated from French by Elizabeth Palmer Peabody.[19][20]

Idealism[edit]

Transcendentalists differ in their interpretations of the practical aims of will. Some adherents link it with utopian social change; Brownson, for example, connected it with early socialism, but others consider it an exclusively individualist and idealist project. Emerson believed the latter. In his 1842 lecture "The Transcendentalist", he suggested that the goal of a purely transcendental outlook on life was impossible to attain in practice:

Importance of nature[edit]

Transcendentalists have a deep gratitude and appreciation for nature, not only for aesthetic purposes, but also as a tool to observe and understand the structured inner workings of the natural world.[4] Emerson emphasizes the Transcendental beliefs in the holistic power of the natural landscape in Nature:

The conservation of an undisturbed natural world is also extremely important to the Transcendentalists. The idealism that is a core belief of Transcendentalism results in an inherent skepticism of capitalism, westward expansion, and industrialization.[22] As early as 1843, in Summer on the Lakes, Margaret Fuller noted that "the noble trees are gone already from this island to feed this caldron",[23] and in 1854, in Walden, Thoreau regards the trains which are beginning to spread across America's landscape as a "winged horse or fiery dragon" that "sprinkle[s] all the restless men and floating merchandise in the country for seed".[24]

Influence on other movements[edit]

| Part of a series of articles on |

| New Thought |

|---|

Transcendentalism is, in many aspects, the first notable American intellectual movement. It has inspired succeeding generations of American intellectuals, as well as some literary movements.[25]

Transcendentalism influenced the growing movement of "Mental Sciences" of the mid-19th century, which would later become known as the New Thought movement. New Thought considers Emerson its intellectual father.[26] Emma Curtis Hopkins ("the teacher of teachers"), Ernest Holmes (founder of Religious Science), Charles and Myrtle Fillmore (founders of Unity), and Malinda Cramer and Nona L. Brooks (founders of Divine Science) were all greatly influenced by Transcendentalism.[27]

Transcendentalism is also influenced by Hinduism. Ram Mohan Roy (1772–1833), the founder of the Brahmo Samaj, rejected Hindu mythology, but also the Christian trinity.[28] He found that Unitarianism came closest to true Christianity,[28] and had a strong sympathy for the Unitarians,[29] who were closely connected to the Transcendentalists.[16] Ram Mohan Roy founded a missionary committee in Calcutta, and in 1828 asked for support for missionary activities from the American Unitarians.[30] By 1829, Roy had abandoned the Unitarian Committee,[31] but after Roy's death, the Brahmo Samaj kept close ties to the Unitarian Church,[32] who strived towards a rational faith, social reform, and the joining of these two in a renewed religion.[29] Its theology was called "neo-Vedanta" by Christian commentators,[33][34] and has been highly influential in the modern popular understanding of Hinduism,[35] but also of modern western spirituality, which re-imported the Unitarian influences in the disguise of the seemingly age-old Neo-Vedanta.[35][36][37]

Major figures[edit]

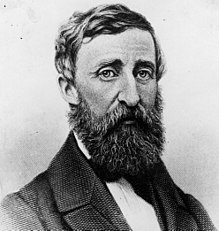

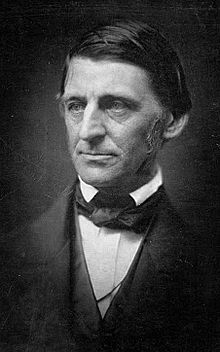

Major figures in the transcendentalist movement were Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, Margaret Fuller, and Amos Bronson Alcott. Some other prominent transcendentalists included Louisa May Alcott, Charles Timothy Brooks, Orestes Brownson, William Ellery Channing, William Henry Channing, James Freeman Clarke, Christopher Pearse Cranch, John Sullivan Dwight, Convers Francis, William Henry Furness, Frederic Henry Hedge, Sylvester Judd, Theodore Parker, Elizabeth Palmer Peabody, George Ripley, Thomas Treadwell Stone, Jones Very, and Walt Whitman.[38]

Criticism[edit]

Early in the movement's history, the term "Transcendentalists" was used as a pejorative term by critics, who were suggesting their position was beyond sanity and reason.[39] Nathaniel Hawthorne wrote a novel, The Blithedale Romance (1852), satirizing the movement, and based it on his experiences at Brook Farm, a short-lived utopian community founded on transcendental principles.[40]

Edgar Allan Poe wrote a story, "Never Bet the Devil Your Head" (1841), in which he embedded elements of deep dislike for transcendentalism, calling its followers "Frogpondians" after the pond on Boston Common.[41] The narrator ridiculed their writings by calling them "metaphor-run" lapsing into "mysticism for mysticism's sake",[42] and called it a "disease". The story specifically mentions the movement and its flagship journal The Dial, though Poe denied that he had any specific targets.[43] In Poe's essay "The Philosophy of Composition" (1846), he offers criticism denouncing "the excess of the suggested meaning... which turns into prose (and that of the very flattest kind) the so-called poetry of the so-called transcendentalists".[44]

See also[edit]

- Dark romanticism

- Freemasonry

- Immanentism

- Self-transcendence

- Transcendence (religion)

- Fruitlands

- The Machine in the Garden

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Versluis: "In American Transcendentalism and Asian religions, I detailed the immense impact that the Euro-American discovery of Asian religions had not only on European Romanticism, but above all, on American Transcendentalism. There I argued that the Transcendentalists' discovery of the Bhagavad-Gita, the Vedas, the Upanishads, and other world scriptures was critical in the entire movement, pivotal not only for the well-known figures like Emerson and Thoreau, but also for lesser known figures like Samuel Johnson and William Rounsville Alger. That Transcendentalism emerged out of this new knowledge of the world's religious traditions I have no doubt."[17]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b c d Goodman, Russell (2015). "Transcendentalism". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. "Transcendentalism is an American literary, political, and philosophical movement of the early nineteenth century, centered around Ralph Waldo Emerson."

- ^ Wayne, Tiffany K., ed. (2006). Encyclopedia of Transcendentalism. Facts On File's Literary Movements. ISBN 9781438109169.

- ^ "Transcendentalism". Merriam Webster. 2016."a philosophy which says that thought and spiritual things are more real than ordinary human experience and material things"

- ^ a b Finseth, Ian. "American Transcendentalism". Excerpted from "Liquid Fire Within Me": Language, Self and Society in Transcendentalism and Early Evangelicalism, 1820-1860, - M.A. Thesis, 1995. Archived from the original on 16 April 2013. Retrieved 18 April 2013.

- ^ Miller 1950, p. 49.

- ^ Versluis 2001, p. 17.

- ^ Finseth, Ian Frederick. "The Emergence of Transcendentalism". American Studies @ The University of Virginia. The University of Virginia. Retrieved 9 November 2014.

- ^ "George Putnam", Heralds, Harvard Square Library, archived from the original on March 5, 2013

- ^ Rose, Anne C (1981), Transcendentalism as a Social Movement, 1830–1850, New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, p. 208, ISBN 0-300-02587-4.

- ^ Gura, Philip F (2007), American Transcendentalism: A History, New York: Hill and Wang, p. 8, ISBN 978-0-8090-3477-2.

- ^ Stevenson, Martin K. "Empirical Analysis of the American Transcendental movement". New York, NY: Penguin, 2012:303.

- ^ Wayne, Tiffany. Encyclopedia of Transcendentalism: The Essential Guide to the Lives and Works of Transcendentalist Writers. New York: Facts on File, 2006: 308. ISBN 0-8160-5626-9

- ^ Sacks, Kenneth S.; Sacks, Professor Kenneth S. (2003-03-30). Understanding Emerson: "The American Scholar" and His Struggle for Self-reliance. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691099828.

institutions.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo. "The Over-Soul". American Transcendentalism Web. Retrieved 13 July 2015.

- ^ "EMERSON--"THE AMERICAN SCHOLAR"". transcendentalism-legacy.tamu.edu. Retrieved 2017-10-14.

- ^ a b Versluis 1993.

- ^ a b Versluis 2001, p. 3.

- ^ Thoreau, Henry David. Walden. Boston: Ticknor&Fields, 1854.p.279. Print.

- ^ Lopez Jr., Donald S. (2016). "The Life of the Lotus Sutra". Tricycle Magazine (Winter).

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo; Fuller, Margaret; Ripley, George (1844). "The Preaching of Buddha". The Dial. 4: 391.

- ^ Emerson, Ralph Waldo. "Nature". American Transcendentalism Web. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- ^ Miller, Perry, 1905-1963. (1967). Nature's nation. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674605500. OCLC 6571892.

- ^ "The Project Gutenberg eBook of Summer on the Lakes, by S. M. Fuller". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- ^ "Walden, by Henry David Thoreau". www.gutenberg.org. Retrieved 2019-04-15.

- ^ Coviello, Peter. "Transcendentalism" The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Web. 23 Oct. 2011

- ^ "New Thought", MSN Encarta, Microsoft, archived from the original on 2009-11-02, retrieved Nov 16, 2007.

- ^ INTA New Thought History Chart, Websyte, archived from the original on 2000-08-24.

- ^ a b Harris 2009, p. 268.

- ^ a b Kipf 1979, p. 3.

- ^ Kipf 1979, p. 7-8.

- ^ Kipf 1979, p. 15.

- ^ Harris 2009, p. 268-269.

- ^ Halbfass 1995, p. 9.

- ^ Rinehart 2004, p. 192.

- ^ a b King 2002.

- ^ Sharf 1995.

- ^ Sharf 2000.

- ^ Gura, Philip F. American Transcendentalism: A History. New York: Hill and Wang, 2007: 7–8. ISBN 0-8090-3477-8

- ^ Loving, Jerome (1999), Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself, University of California Press, p. 185, ISBN 0-520-22687-9.

- ^ McFarland, Philip (2004), Hawthorne in Concord, New York: Grove Press, p. 149, ISBN 0-8021-1776-7.

- ^ Royot, Daniel (2002), "Poe's humor", in Hayes, Kevin J (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, Cambridge University Press, pp. 61–2, ISBN 0-521-79727-6.

- ^ Ljunquist, Kent (2002), "The poet as critic", in Hayes, Kevin J (ed.), The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, Cambridge University Press, p. 15, ISBN 0-521-79727-6

- ^ Sova, Dawn B (2001), Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z, New York: Checkmark Books, p. 170, ISBN 0-8160-4161-X.

- ^ Baym, Nina; et al., eds. (2007), The Norton Anthology of American Literature, vol. B (6th ed.), New York: Norton.

Sources[edit]

- Halbfass, Wilhelm (1995), Philology and Confrontation: Paul Hacker on Traditional and Modern Vedānta, SUNY Press

- Harris, Mark W. (2009), The A to Z of Unitarian Universalism, Scarecrow Press

- King, Richard (2002), Orientalism and Religion: Post-Colonial Theory, India and "The Mystic East", Routledge

- Kipf, David (1979), The Brahmo Samaj and the shaping of the modern Indian mind, Atlantic Publishers & Distri

- Miller, Perry, ed. (1950). The Transcendentalists: An Anthology. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674903333.

- Rinehart, Robin (2004), Contemporary Hinduism: ritual, culture, and practice, ABC-CLIO

- Sharf, Robert H. (1995), "Buddhist Modernism and the Rhetoric of Meditative Experience" (PDF), Numen, 42 (3): 228–283, doi:10.1163/1568527952598549, hdl:2027.42/43810, archived from the original (PDF) on 2019-04-12, retrieved 2013-11-01

- Sharf, Robert H. (2000), "The Rhetoric of Experience and the Study of Religion" (PDF), Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7 (11–12): 267–87, archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-05-13, retrieved 2013-11-01

- Versluis, Arthur (1993), American Transcendentalism and Asian Religions, Oxford University Press

- Versluis, Arthur (2001), The Esoteric Origins of the American Renaissance, Oxford University Press

Further reading[edit]

- Dillard, Daniel, “The American Transcendentalists: A Religious Historiography”, 49th Parallel (Birmingham, England), 28 (Spring 2012), online

- Gura, Philip F. American Transcendentalism: A History (2007)

- Harrison, C. G. The Transcendental Universe, six lectures delivered before the Berean Society (London, 1894) 1993 edition ISBN 0 940262 58 4 (US), 0 904693 44 9 (UK)

- Rose, Anne C. Social Movement, 1830–1850 (Yale University Press, 1981)

External links[edit]

Topic sites

- The web of American Transcendentalism, VCU

- The Transcendentalists

- "What Is Transcendentalism?", Women's History, About

- The American Renaissance and Transcendentalism

Encyclopedias

- "American Transcendentalism". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- "Transcendentalism", Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Stanford, 2019}

Other