2023/03/26

Okakura Kakuzō: A Reintroduction

Okakura Kakuzō: A Reintroduction

Author(s): Noriko Murai and Yukio Lippit

Source: Review of Japanese Culture and Society, Vol. 24,

Beyond Tenshin: Okakura Kakuzo's Multiple Legacies (DECEMBER 2012), pp. 1-14

Published by: University of Hawai'i Press

Okakura Kakuzö: A Reintroduction

Noriko Murai and Yukio Lippit

In 1905, Okakura Kakuzö (1863-1913)' designed a small hexagonal pavilion that overlooks the Pacific Ocean by Izura Bay on his country estate in rural Ibaraki Prefecture and named it Kanrantei (Big Wave Viewing Pavilion). Commonly known as Rokkakudö (Six-Sided Hall), the recently reconstructed Kanrantei, destroyed by the tsunami of March 11, 2011 (see frontispiece to the volume), serves as an architectural analogue for the complexity of Okakura's historical persona and discursive profile. It invokes many of the characteristics associated with this turn-of-the-century transnational intellectual who played such a significant role in the art and cultural patrimony of the Meiji era (1868-1912). While the six-sided Rokkakudö appears deeply rooted in the traditional architectural typologies of East Asia, its classicism is in fact inventive, as it represents a rare building form with no major precedents or obvious points of reference.2 Not only is the symbology of its form obscure, but so are the circumstances surrounding its construction—as part of the sequence of events related to the relocation of the Japan Art Institute (Nihon Bijutsuin) from Yanaka in central Tokyo to the remote fishing village of Izura. It evokes the momentary isolation of this major Meiji-era alternative art institution founded by Okakura, and by extension his renegade reputation and cult-like status among his circle of artist-friends. Furthermore, the Rokkakudö's setting, a rocky outcropping off of the Izura Coast, resonates with Okakura's self-image as an exilic and reclusive figure. The dramatic vantage point it offers onto the Pacific Ocean manifests its creator's own far-reaching vision and an overseas career that witnessed extended sojourns in Boston and Calcutta, as well as shooter stays throughout Europe and China. The Rokkakudö embodies the erudition, antinomianism, and internationalism that so indelibly marked Okakura's own career.

The destruction and subsequent rebuilding of the hexagonal structure also provide

a timely pretext for a reconsideration of Okakura's discursive legacy. This legacy has been conditioned by the prerogatives of specific interpretive communities throughout the twentieth century. Their cumulative effect has been the mythologization of “Okakura Tenshin” as the father of pan-Asianist discourse, and a casting of him as the father of modem Japanese art. The present issue of the Review ofJapanese Culture and Society was conceived from a position of skepticism with regard to such epithets. Its main proposition, as explored through the articles by noted specialists found in this volume, is that a close reading of Okakura's writings and circumstances presents a more subtle and complex historical profile, and raises different types of questions: What are the main thèmes and commitments of Okakura's body of writings? How might thèse writings be understood as unified? How did the radically disparate environments through which Okakura moved inflect his thought? And how did he conceptualize the history of Japanese art at the end of his life, after playing central roles in the government-led surveys of cultural treasures in the 1880s, the founding of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts (Tökyö Bijutsu Gakkö) and the Japan Art Institute, and the amassment of an Asian art collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston? Even though we fall far short of answering thèse questions in full, it is our conviction that a sustained attention to them opens up new and oblique ways of understanding both the historical position of Okakura and the contingencies of the Meiji art world.

In adopting this approach, we have been inspired by the writings of Kinoshita Nagahiro (also a contributor to the present volume), who has disarticulated more than anyone the many myths of Okakura. And in keeping with Kinoshita's practice, whenever referring to Okakura, we have chosen to avoid the common sobriquet “Tenshin” that has come to be associated with a specific way of imagining Okakura, and instead have chosen to call him by his given name, Kakuzö. As Kinoshita reminds us in his essay included in this volume, “Tenshin” was one of the names Okakura occasionally used when signing his personal letters and poems, although he never used this name in public. It was Okakura's close associates at the Japan Art Institute who began calling him “Tenshin” posthumously out of reverence, and the Japanese rediscovery of Okakura as “Okakura Tenshin” in the 1930s was predicated on this essentially hagiographical tradition. There is a need to distinguish Okakura Kakuzö from his much romanticized afterlife as Tenshin. Hence the title of this special issue, “Beyond Tenshin: Okakura Kakuzö's Multiple Legacies.”

In surveying the historiography of Okakura, several moments stand out as especially important in shaping his reception.' The first moment arose in the 1930s, two decades after his passing. It was from the wartime period of the 1930s through 1945 that the Japanese intellectual community rediscovered Okakura and created the influential image of “Tenshin” as the visionary pan-Asianist who asserted, “Asia is one.” It was not until the mid-1930s that the complete works of Okakura, including a full Japanese translation of his English books, were published, appearing under the name “Okakura Tenshin.”’

Seibunkaku published a three-volume collected works (Okakura Tenshin zenshü) in 1935-36, and Rikugeisha published a five-volume collected works with the same title in 1939; both sets were edited by Okakura's son Kazuo. The Society to Commemorate the Accomplishments of Okakura Tenshin (Okakura Tenshin Iseki Kenshökai), established in 1942 and led by the Nihonga painter Yokoyama Taikan, also began to publish yet another set of collected works (Tenshin zenshti) in 1944, but Japan's defeat in the war the following year left this project unfinished. As for more accessible publications, Iwanami published a paperback translation of The Book of Tea in 1929, followed by The Awakening of Japan in 1940, and The Ideals of the East in 1943.5 Okakura wrote all of his books in English, which were materially available in Japan, but intellectually accessible only to a limited readership, and therefore it is not an exaggeration to state that Okakura was not well known in Japan as a thinker until his writings became available through these Japanese translations. The re-emergence of Okakura as “Tenshin” was the result of the various efforts of a number of institutions and individuals, including Okakura's family (his son Kazuo and Okakura's younger brother Yoshisaburö, a prominent scholar of English), artists of the Japan Art Institute led by Yokoyama Taikan, the Tokyo School of Fine Arts, and critics such as Yasuda Yojtirö and Kamei Katsuichirö, who were associated with the literary joumal The Japan Romantic School (Nihon Roman-ha; published between 1935 and 1938).6

The literary critic Yasuda Yojiirö in particular played an instrumental role in forging

the mythology of Tenshin as a prophet of Asian spiritual unity. In his 1942 exegesis of “Asia is One (Ajia wa hitotsuda),” Yasuda called Okakura the greatest Meiji thinker and the most exemplary patriot (shishi),7 and cited the nationalist poet Asano Akira in declaring Okakura's writings to be Meiji Japan's greatest “war literature.”” “Asia is One” began to take on a life of its own with “O” capitalized (in symbolic alteration of the non-capitalized “o” in the original). In 1944, “Ajia wa hitotsu” was selected as the aphorism of the day for December 8, the day that marked the beginning of the “Greater East Asia War,” in the propaganda calendar Almanac of National Aphorisms (Kokumin zayii no mei) edited by the Patriotic Association for Japanese Literature (Nihon Bungaku Hökokukai).9 There is little doubt that the name “Tenshin” was invoked to justify Shöwa Japan's war in Asia and the Pacific as the necessary and cumulative destiny of modern Japan.

The 1938 discovery of a short unpublished manuscript that Okakura wrote in English during his first stay in India in 1901-2 also helped to cement his heroic image as a visionary pan-Asian thinker.'0 This manuscript contains heated passages, such as “The glory of Europe is the humiliation of Asia!” and “European imperialism has itself fumished the weapons by which it shall be destroyed.”'1 Okakura wrote it during his intense collaöorative phase with Margaret Noble (aka Sister Nivedita, 1867-1911), whose own agenda of anti-colonial agitation also hovers over Okakura's The Ideals of the East. In 1939, the poet Asano Akira, a former-Communist-turned-ultranationalist who began to

write prolifically on Okakura during wartime, translated and published this manuscript under the title The Awakening ofthe East(Töyö no kakusei). Though this title was Asano's invention, its catchy resonance with Okakura's own titles The Ideals of the East and The Awakening of Japan has made it the standard “title” for this originally untitled piece of writing to this day. As with the phrase “Asia is one,” this text too has been accorded an outsized importance in the inflation of Okakura as a pan-Asian ideologue.

Okakura's wartime reputation has shaped subsequent historiography in Japan in a number of ways. First, it resulted in a powerful cult of personality, one that went well beyond the coterie of Okakura's close associates at the Japan Art Institute who were the first to venerate Okakura as “Tenshin” shortly after his death. This personality cult revolved around the still popular image of Okakura as a tragic hero, whose lofty ideals went unrealized because they went against the prevailing tide of his time.1' This mournful pathos that pervades Yasuda's discussion of Okakura reveals a highly aestheticized fascination with imminent loss, death, and defeat that is also present in Yasuda's other writings. It is significant that Yasuda's characterization of Okakura, rendered in his notoriously opaque, self-indulgent style, is far from the simplistic portrayals that one typically associates with state propaganda. In fact, the very appeal of Yasuda's writings at the height of the Pacific War rested on an ornate literariness that set them apart from the impoverished prose of military-fed propaganda. It is perhaps also for this reason that the critic Takeuchi Yoshimi, in his 1962 essay on Okakura, translated in this volume, observed that “[d]etaching Tenshin from fascism is not too hard, but detaching him from the Japan Romantic School's interpretation is not accomplished as easily as one might expect.” Although the propagandistic appropriation of “Tenshin” during wartime is now well understood as a stain on Okakura's profile, the actual content of the Tenshin myth that so captivated the Japanese intellectual community at the time still awaits careful examination." Only such an analysis will finally enable us to assess how the writings by the Japan Romantic School have mediated our own imagination of Okakura.

Another consequence of the wartime rediscovery of Okakura is that he was reintroduced in Japan more as a pan-Asian ideologue than as an art historian. As Inaga Shigemi points out in his essay in this volume, this discontinuity of Okakura’s intellectual legacy in Japan had been prepared by what he terms the “patricide” of Okakura by subsequent art historians. As a result, the most sustained interpretative tradition on Okakura to this day is constituted by scholars of intellectual history rather than of art, including figures such as Maruyama Masao, Hashikawa Bunzö, Takeuchi Yoshimi, and Matsumoto Ken'ichi more recently. Critiqued from an array of ideological positions, Okakura continues to be regarded as a key figure through which to reflect on the nature of Japan's modernity and the meaning of its geocultural position in Asia." We have chosen to translate Takeuchi’s short yet influential essay “Okakura Tenshin: Civilization Critique from the Standpoint of Asia” (1962) as representative

of this interpretative approach. Takeuchi was a leading postwar thinker on the left, who sought an alternative intellectual tradition for modernity in Asia, most notably in revolutionary China.'5 In this vein, he also argued, and not without controversy, that Japanese pan-Asianism contained a legitimate critique of Eurocentric modernity. Within this larger project, Takeuchi came to position Okakura as an early critic of Eurocentric modernity who believed in the equation of “beauty, spirit, and Asia,” and presented The Ideals of the East as the pinnacle of Okakura's achievement as a thinker (despite his own warning that this text alone does not represent the entirety of Okakura's significance). While this casting of Okakura as a committed critic of Western-style modernisation prefigures similar re-castings of Okakura from a post-colonial perspective, Takeuchi’s interpretation is unable to offer a convincing discussion of Okakura's career in the Meiji cultural bureaucracy or his later curatorial work in Boston, as neither supports the image of Okakura as a strict opponent of Western-style modernity inside or outside Japan.

The second significant moment in the historiography of Okakura can be situated in the 1990s, a moment that is still proximate to us. In the 1990s, the Japanese scholarly community became engaged in a self-reflective critique of its own history as institution, prompted by the widespread sentiment that a particular phase of modernity had ended. This awareness was reinforced by the end of the long Shöwa era (1926-89) and the bursting of the so-called bubble economy. In this postmodern climate, the invented nature of Japan as nation state (kokumin kokka) came to the fore. Art historians such as Kitazawa Noriaki and Satö Döshin published seminal works that investigated the discourse of bijutsu (fine art) as a constitutive element in the production and maintenance of national identity in modem Japan. If Japanese artists have been engaged in the institutional critique of art since the 1960s, it was not until the 1990s that the community of art historians and museum curators began to pursue a similar critique of their own system. In this new line of inquiry, Okakura was positioned as a key figure who conceived the very idea of “Japanese art” as we know it today. In the 1990s Okakura also began to receive serious scholarly attention by Japan specialists outside Japan as an early architect of Japanese cultural nationalism.'6

This recent wave of scholarly literature has benefitted from the sustained archival

research and documentation that culminated in the two multi-volume publication projects of Okakura's collected writings in both Japanese (1979-1980; nine volumes) and English (1984; three volumes) by Heibonsha. Thèse Heibonsha publications represent a substantial upgrade from the last publication project of a similar magnitude that took place during the wartime. And yet, the impetus to compile thèse resources was rooted in the personality cult of Okakura. In the mid-1960s, the Nihonga painter Yasuda Yukihiko, then a doyen of the Nihonga establishment as chairman of the Japan Art Institute and a representative of the last generation to know Okakura in person, expressed the desire to produce an authoritative monograph on Okakura to commemorate the centennial of his

birth, which led to the publication of his collected writings. As Satö Döshin has observed, in the 1960s, as Japan prepared to observe the centennial of the Meiji Restoration, there was a widespread effort to preserve primary materials and documentary accounts of Meiji Japan.'7 Around this time the art of the Meiji period also began to be integrated into the scholarly field of Japanese art history. The critical re-assessment of Okakura's legacy, together with the compilation of related primary materials, was an integral part of this discursive process of transforming Meiji into history.

The site of Izura, already mentioned at the beginning of our introduction, has played an important role in this postwar afterlife of Okakura, in mediating the tradition of the “Tenshin” personality cult that intensified during the wartime and the more recent reevaluation of Okakura as a historical figure of academic interest. The movement to preserve the Izura property epitomized the wartime worship of Tenshin catalyzed by figures such as Yokoyama Taikan. After the war, in 1955, the estate was entrusted to Ibaraki University by Taikan, and in 1963 a memorial museum was established with a collection of artworks donated by families of Okakura's close associates at the Japan Art Institute as well as by living members of the Institute. In 1971, the Izura estate was renamed the Izura Institute of Arts and Culture (Izura Bijutsu Bunka Kenkyûjo), and the Institute's annual publication Izura Collection of Essays (Izura ronsö) has provided a forum to promote scholarship on Okakura. The memorial museum, rehoused in a new building designed by Naitö Hiroshi, was reopened as the Tenshin Memorial Museum in 1997. In this way, Izura serves the double role of a center for Okakura studies and a local tourist attraction that ensures the popularity of Okakura as a cultural icon.

Another notable aspect of Okakura's reassessment since the 1990s is his reevaluation as one of the first transnational intellectuals from Asia who mediated the cultures of East and West (or, perhaps more accurately, as someone who proposed an influential self- definition of “the East” through a strategic alignment and distanciation from the equally putative “West”). This approach has been informed by Orientalism and postcolonial studies. Historians of modem Indian art and culture have investigated the significance of Okakura in the discursive making of “Indianness” in the early twentieth century, for example, while scholars in North America have paid renewed attention to the influential role Okakura played in the American imagination of the East. In contrast to the more “traditional” pan-Asianist reading of Okakura, Okakura’s vision of the East in this recent body of literature is assessed less in terms of its political impact, nor does it seek to place Okakura into a genealogy of pan-Asianism. Instead, this recent literature seeks to consider, perhaps for the first time, the transnational meaning of Okakura's career and thought on art. As representative of this approach, we have selected to translate the article by Inaga Shigemi titled “Okakura Kakuzö and India: The Trajectory of Modem National Consciousness and Pan-Asian Ideology Across Borders” (2004). Inaga positions Okakura’s interpretation of Asian art within the complex international debate that preoccupied Indian, British, and Japanese art historians around the turn of the twentieth

century. Inaga's interest in Okakura resonates with the broader intellectual concern of the art history community worldwide today to re-examine its own history and practice from a more global perspective, and to explore possibilities of a history of art that does not simply reify the geocultural binarism of the West and the rest.

This cursory review of the reception of Okakura shows that his legacy has been defined in ways that, in hindsight, clearly served the needs of specific communities of thinkers and institutions. The present volume consciously positions itself vis-ñ-vis this commentarial history and its various lacunae. Accordingly, what the essays gathered here contribute is an intensively local approach to a number of micro-contexts surrounding Okakura’s doings and writings, in the process reconceiving the raw material from which to assess his career. Two examples suffice to introduce this manner of approach, centering around Okakura's two most famous texts, The Ideals of the East (1903) and The Book of Tea (1906).

The latter text has been hailed as a highly influential and, for its time, definitive summa of Japanese aesthetics and its relationship to the tea ceremony, as formulated by Okakura for Western audiences. A closer look at the context in which The Book of Tea was authored, however, offers a more fine-grained assessment of the audiences presupposed by Okakura for his exposition of “Teaism.” As Allen Hockley discusses in his contribution to this issue, at the turn of the century Japanese tea culture was poorly understood and chanoyu the subject of much misinformation. These mischaracterizations appear to have conditioned, at least to some extent, the agenda of The Book of Tea. Noriko Murai’s essay included here argues for the importance of reading The Book of Tea against the context of Okakura's highly performative role of a Japanese aesthete to Boston high society. His interactions with members of the Isabella Stewart Gardner circle as a chanoyu master proved to have been a particularly effective medium for the introduction of Japanese aesthetic ideas to these prominent cultural figures in Boston.

As the historiographical survey above makes clear, The Ideals of the East, celebrated (or vilified) for its opening line, “Asia is one,” has generally been understood as an early and forceful articulation of pan-Asianism. As Kinoshita notes in his essay here, however, Okakura only used the phrase “Asia is one” (with “one” uncapitalized in the original) for the opening of The Ideals of the East, he never repeats it, or any similar phrase, in any of his other published writings." Indeed, it is difficult to discern elsewhere in the text or in Okakura's other major writings an explicitly political expression of pan- Asianism associated with this expression, let alone the expansive Japanese ultranational- ism often assumed from it under the banner of Asian solidarity. There is no doubt that the intellectual and artistic empathy Okakura experienced in India left a lasting impact on his conception of Asia. He was also among the first intellectuals in Asia to voice a critique of modern Eurocentrism by turning its cultural logic against itself and by proposing an alternative geo-cultural heritage, however inventive.1’ At the same time, this opening line has been allowed to play an outsized role as an epigraph for Okakura's legacy.

Rather, it is more important to assess The Ideals of the East within the context of Okakura's transformative travels and evolving networks at the turn of the century. Most important among thèse was his relationship with Margaret Noble, otherwise known as Sister Nivedita. As John Rosenfield explores in his essay for this volume, Okakura's text was authored through close partnership with Nivedita, and was the result of a momentary confluence of historical trends circa 1900, including the emergence of interfaith dialogue, the popularity of Swami Vivekänanda and the therapeutic aestheticism of “Eastem spirituality” in Boston high society, Okakura's promotion of the Japan Art Institute artists, and the Indian independence movement. Furthermore, as Inaga argues in “Okakura Kakuzö and India,” The Ideals of the East was in dialogue with an emerging discourse on “Eastern art history” during the first decade of the twentieth century. Positioning the authorship of The Ideals of the East within this complex calculus of historical phenomena is more meaningful than understanding it as the static reflection of its author's purportedly strident pan-Asianism. Indeed, Okakura did not pursue pan-Asianism as an anti-colonial political ideology beyond the brief Indian moment of 1902, and there is some reason to believe that Okakura distanced himself from the book in later years, as reflected in his refusal to sign off on a Japanese translation of Ideals.

Embedding Okakura within more fine-grained analyses of turn-of-the-century developments in Japanese artistic culture can yield dividends well beyond the monographic. As Victoria Weston demonstrates in her contribution to the present issue, Okakura's aspirations for the work of the Japan Art Institute painters come into higher relief when the critique sessions in which he engaged with painter-colleagues and published in the journal Nihon bi jutsu (Japanese Art) are read closely. There it becomes apparent that the commonly employed term mörötai, now a standard way of designating the “hazy paintings” of the early years of the Japan Art Institute, is far less revealing than the term risöga or “ideal painting” for understanding the artistic agendas of this ambitious circle of Nihonga artists and critics. By the same token, Alice Tseng’s contribution on the ever-evolving discursive profile of the term kenchiku (architecture) and its cognates parallels the fast-paced metabolism of the Meiji art world in which Okakura was formed and served as a key arbiter. Chelsea Foxwell's essay on antiquarian culture in mid Meiji, meanwhile, provides a crucial context for what she terms “Okakura's Hegelianism,” in which his study of antiquities and views on contemporary artistic production were conceptualized within a continuum whose seamlessness has been obscured over time.

The present issue on Okakura also introduces a substantial body of Okakura's Japanese writings on art in English translation for the first time.20 It includes English translations of three pieces of writing that Okakura published in Japanese in the late nineteenth century, when he actively shaped Meiji art policies through his double appointment as the headmaster of Japan's newly established national academy of fine arts and the director of the fine arts section of the national museum. Okakura was an

influential public voice during his time and wrote on a wide range of subjects from art education to art policies, art history, and contemporary art. While our selection does not cover all of thèse areas or the breadth of Okakura's ever-evolving thoughts on art, each of the three texts translated here marks an important moment in Okakura's career and provides a sense of his multifaceted interests.

The first piece, “Reading ‘Calligraphy Is Not Art”’ (1882), is well known as instigating one of the first public debates on art, one that animated Meiji journalism. It also marked Okakura's journalistic debut at the age of 19 as a young civil servant in the Ministry of Education. It was written in critical response to an argument presented by the oil painter Koyama Shötarö (1857-1916), who questioned the “fine art” (bijutsu) status of calligraphy according to Western-inflected artistic criteria. In seeking to refute Koyama's case and provoke a public debate, which ultimately never occurred as Koyama did not respond, Okakura drew not only on the rich cultural heritage of East Asia but also on modem European aesthetic criteria, especially the definition of the aesthetic as disinterested and non-useful. This approach echoes the one employed by Okakura's mentor Fenollosa, who had delivered his seminal lecture “The True Meaning of the Fine Arts” (Bijutsu shinsetsu) to the Ryiichikai (Dragon Pond Society) just a few months earlier.

It is also notable that Koyama stood at the unfavorable end of this debate from the beginning. By his own admission, Koyama's refutation of the fine art status of calligraphy represented a minority position in the early 1880s, especially if the idea of “fine art” were to be equated with a sense of high cultural achievement of a given civilization. The privileged position accorded to calligraphy as exemplar of high culture was never abandoned during Meiji, as witnessed by the popularity of the literati tradition even among the newcomer elite. It further disadvantaged Koyama's position that the value of Western-style painting for Meiji culture was temporarily being questioned around this time; the year 1882 witnessed the closing of Japan's first national art school, the College of Engineering Art School (Köbu Bijutsu Gakkö) that exclusively taught Western media, as well as the rejection of oil painting for the First Domestic Competitive Painting Exhibition (Naikoku Kaiga Kyöshinkai). Okakura seemed aware that general public sentiment was against Koyama's position, and was careful not to appear as a member of an “old” conventional bandwagon looking to crush Koyama's “new,” Westernizing position. Thus he begins by declaring that “it is of course not my wish to assume the responsibility of speaking in defense of commonly held fallacies.” Okakura's critique of Koyama's argument focuses on the fact that his analysis is not “enlightened” enough to take account of more universal and a priori criteria for aesthetic judgment. Okakura claims that a good part of Koyama's argument can be reduced to the simple observation that calligraphy is neither painting nor sculpture. This, Okakura argues, does not constitute a worthy aesthetic critique.

The second translated text included here is the inaugural address to the art magazine Kokka (Flowers of the Nation) that Okakura launched in October 1889 with the journalist

Takahashi Kenzo. The journal title alone suggests the role Okakura envisioned art to play in national life. This address was not attributed to a specific individual, but all surrounding circumstances as well as the writing itself point to Okakura's authorship. Kokka began as a deluxe magazine that specialized in art and was the first of its kind in Japan. It remains in publication to this day as a leading academic journal of East Asian art history. The publication of Kokka added yet another dimension to Okakura's already commanding web of influence in the Meiji art world, this time by initiating a public forum to promote a more scholarly understanding of Japanese art. In this inaugural issue, Okakura himself contributed an essay on the Edo-period painter Maruyama fikyo. By 1889, having ousted his opponents in the Ministry of Education such as Koyama, Okakura had risen to a position of bureaucratic prominence as the person in charge of the newly established Tokyo School of Fine Arts. In this year he was furthermore appointed the director of the fine arts section of the museum in Ueno, which was renamed the Imperial Museum. Throughout the Kokka inaugural address, the sense of national pride that Okakura exhorts the public to embrace resonates with a heightened awareness that Meiji Japan had finally become a mature state following the promulgation of the Imperial Constitution earlier in the same year.

In “Concerning the Institutions of Art Education” (1897), the third text translated here, Okakura develops his proposition of a grand vision for national art policy, in this case the improvement of art education at the level of secondary and higher institutions of learning. These opinions are the result of a more experienced and learned Okakura, someone who had now served as a top art official for several years. His active involvement with the Japanese exhibit at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair as well as the planning for the 1900 Paris Universal Exposition also inflect his concern for the competitiveness of Japanese manufacture in overseas markets. Although Okakura is often seen as Tokyo- centric and primarily interested in the fine art category of painting, this text reflects his sustained concern for the preservation and promotion of traditional craftsmanship and other region-specific manufacturing industries throughout Japan. What strikes the reader, above all, is the wide gap that continues to exist between Okakura's ambitious vision of national art administration, already detected in his Kokka address, and the actual state of national art policies at the end of the nineteenth century. Okakura proposes that the government open another national fine arts academy in Kyoto, for example, along with several technical art schools throughout the nation, each specializing in region-specific craft media such as textiles or ceramics. He also proposes to build about a dozen local museums that display regional craft heritage in order to promote local manufacturing industry. Such far-reaching ideas, however, may have compromised Okakura's standing in the Meiji bureaucracy. It is not difficult to imagine how such excessive demands on state resources may not have endeared him to government officials. Indeed, such views may have contributed to Okakura's forced resignation from both the art school and the museum a year later in 1898, an ouster often explained as directly triggered by a personal

scandal but more broadly contextualized in terms of the ascendency of Western-style painting led by the Paris-trained oil painter Kuroda Seiki.

Is there an aggregate image of Okakura and Meiji artistic culture that results from these scholarly essays and translated texts? Two preliminary responses are all that we dare offer at this point. The first is the idea of a site-specific Okakura. Even though his range of activities spanned the globe and was predicated upon vital relationships with numer- ous overseas collaborators, Okakura's discursive acts have been, for the most part, im- precisely mapped onto the rapidly evolving cartography of global power relations and emerging nation-states of the modem era. Embedding Okakura in each of his discrete micro-contexts goes beyond mere biographical excavation in its exploration of the ways his thought is tied to international networks of individuals, the exploratory agendas of new types of art institutions, and the unpredictable dynamics of contact zones. While such formulations may appear to contradict the self-contained points of inquiry implied by “site-specificity,” in fact the widely scattered coordinates of Okakura's most significant achievements each represent a momentary convergence of peoples, experiences, historical trends, and local circumstances specific to that place and time, whether it be his inaugural art history lectures at the Tokyo School of Fine Arts in 1890, his residency in Calcutta in early 1902, or his final three lectures on East Asian art at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 1911.

In a related vein, site-specificity also sends a warning that ideas do not travel or transfer from one site to another seamlessly or with transparency. It reminds us that any movement across time and space, by definition, involves rewriting and interpretation. Thus, the site-specific significance of Okakura writing “Asia is one” in Calcutta for a book to be published out of London is not the same as rendering it in Japanese as “Ajia wa hitotsunari” in 1939. Contemplating the distance between “Asia is one” and “Ajia wa hitotsunari” is enough to remind us of the complexity that accompanies acts of cultural translation. And yet, reassessing Okakura as a transnational intellectual requires us to take up such interpretative challenges.

The second tentative image of Okakura that might be yielded in toto from the

inquiries of the present issue is that of an incomplete Okakura. In the final analysis, it may be next to impossible to assign an overarching unity, ideological, philosophical, or otherwise, to a body of writings and lectures that were responding so powerfully to their immediate circumstances. Their author was one of a select group of Japanese intellectuals from his era who could travel widely and engage robustly with the English-language sphere. Thus it is unsurprising that the trajectory of his thinking develops unpredictably as he moves through the disparate environments of his student days at Tokyo University, the newly established Ministry of Education, the meetings of the Kangakai (Painting Appreciation Society) in Tokyo during the 1880s, the directorships (and subsequent resignations therefrom) of the Tokyo School of Fine Arts and the Fine Art section of the

Imperial Museum, his establishment of the Japan Art Institute, his travels in China and India, and his five stays in Boston between 1904— when he took up his work with the Museum of Fine Arts—and his death in 1913. Although there were signs, as Kinoshita Nagahiro discusses, that Okakura was attempting to synthesize his views on the history of Japanese art in his final years, he died before he could realize any systematic exposition thereof. In positing Okakura's thought as incomplete, however, we are by no means implying that there is no value to its systematic and holistic study, that it does not offer a powerful set of ideas and perspectives on the nature and history of Japanese art. Nor do we wish to attribute that incompletion to the often-projected personality of Okakura as a charismatic yet contradictory mind. Rather, it is simply that these ideas and perspectives are too geoculturally diverse and contextually ever-changing to be subject to totalizing rubrics and false unities. What they offer instead are a series of erudite and densely conditioned points of contact with the fast-paced metabolism of the Meiji and globalizing art world from around 1880 to 1910. Okakura's heterogeneous set of achievements, legacies that do not add up to a cohesive, unified whole, are ultimately symptomatic of modernity itself as an asynchronous pulse that is unevenly distributed and experienced from one site, language, and culture to another. In championing this disposition, we hope to inch closer to a meaningful recovery of a historically ensconced and yet dynamically

dispersed, real-time Okakura, before his mythologization, before Tenshin.

====

Notes

1.

1862 is often given as the year of Okakura’s birth, but this is not accurate. The record shows that he was born on the twenty-sixth day of the twelfth month of the second year of the Bunkyii reign. This date in the old lunar calendar corresponds to February 14, 1863 in the Gregorian calendar that the govemment adopted at the end of the fifth year of the Meiji period. This detail yet again points to the transitional nature of the time into which Okakura was born. See Kinoshita Nagahiro, Okakura Tenshin. mono ni kanzureba tsui ni ware nashi (Okak ura Tenshin: In Meditating on the Object, Finally There is No 1) (Kyoto: Minerva Shob0, 2005), 8-12.

2.

Only a handful of hexagonal structures have survived in Japan. There is a hexagonal hall in Tokyo, at Sensöji

in Asakusa, of which Okakura might have been aware. This relative rarity of hexagonal structures is in contrast to the octagonal hall, an architectural form associated with the Chinese imperium, which can be found in Japan as earl y as the Y umedono Hall at HÒry íiji (earl y eighth century). Many famous octagonal haIIs survive in Japan from later eras. Kumada Yumiko has proposed that Okakura's hexagonal hall was intended to serve at once as a Buddhist hall, a Chinese viewing pavilion, and a tearoom. See Kumada, “Rokkakudó no keifu to Tenshin” (The Genealogy of the Six- Sided Hall and Tenshin), in Okakura Tenshin to Izura (Okakura Tenshin and Izura), eds. Morita Yoshiyuki and Koizumi Shin’ya (Tokyo: Chíió Kfiron, 1998), 150-77.

For critical overviews of Okakura’s reception, see Kinoshita Nagahiro,

“‘Okakura Tenshin’ shinwa to ‘Ajia wa h itotsu’ ron no keisei” (The Formation of the ‘Okakura Tenshin’ Myth and the ‘Asia is one’ Theory), in Ta ya ishiki.- musâ to gen jitsu no aida ?887- 952 (Oriental Con- sciousness between Reverie and Reality 1887-1953), ed. Inaga Shi- gemi (Kyoto: Minerva Shobö, 2012), 23-45; and Satö Döshin, “Tenshin kenkyii no genjö to igi” (The Present Status and Significance of Tenshin Scholarship), in Watariumu Bi jutsu- kan no Okakura Tenshin Kenk yiikai (Society for Research on Okakura Tenshin at the Watari Museum of Contemporary Art), ed. Watariumu Bijutsukan, (Tokyo: Yiibun Shoin, 2005), 42-67.

4.

The Japan Art Institute published Okakura's collected writings (Tenshin ze nsh ii [The Complete Works of Tenshin]) and a select translation

12 REviEw or jA PAnr sr curiu Rr •riD soc iETx oscsucsa aola

Noriko Murai and Yukio Lippit

of his English writings (Tenshin sensei öbun chosho shö yaku [Select Translations of Teacher Tenshin's English Writings]) in 1922, but these volumes were prepared as private editions, not for sale.

5.

It is noteworthy that, while effec- tively all publications in Japan that appeared around this time and have appeared since have modified the author's name to “Okakura Tenshin,” these I wanami paperback editions, translated by Muraoka Hiroshi, have retained “Okakura Kakuzõ” as the author's name.

6.

For scholarship in English on the Japan Romantic School, see Kevin Nlichael Doak, Dreams of Difference: The Japan Romantic School and the Crisis of Modernity (Berkeley, Los Angeles, and London: University of California Press, 1994).

7.

Yasuda Yojürõ, “Okakura Tenshin (Asia is One 'Ajia wa hitotsuda’),” in Nihon gorok u (Collection of Japanese Aphorisms, 1942), reprinted in Yasuda Yojcrõ zenshïi (Collected Writings of Yasuda Yojürõ), vol. 17 (Tokyo: Kõdansha, 1987), 176.

8.

Ibid.

89.

The ultranationalist pœt and critic Asa no Akira provided the com- mentary.

10.

Okakura’s grandson Koshirõ dis- covered this manuscript in 1938. The first Japanese translation of this text was published later the same year under the title Rebuilding of the Ideals (Risõ no saiken), edited by Okakura Kazuo and Koshirõ.

11.

Okakura Kakuzo, “The Awakening of the East,” in Okakura Kukuzo, Collected English lVriiings (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1984), I : 136, 159.

12.

For example, the literary critic Ka wak ami Tetsutarõ ( 1902-80), who served as the moderator for the famous 1942 sy mposium on overcoming modernity, portrayed Okakura as one of the emblematic modem Japanese “outsiders” in Ni/ion no autosaidä (Outsiders in Japan) (Tokyo: Chiiõ Kõronsha, 1959), 143-77.

13.

On the Japan Romantic School’s interests in Okakura, see Kyunghee Lee, “Yasuda Yojiirõ no Okak ura Tenshin ron: mittsu no kakyõ no sõ” (Yasuda Yojiirö’s Review of Okakura Tenshin: The Phase of Three Bridges), Hikaku bungaku (Comparative Literature), no. 49 (2006): 52-66 ; ide m , “Kame i Katsuic hirõ no Okakura Tenshin ron: ‘saisei ’ to shite no ‘kaigi”’ (Kamei Katsuichirö’s Review of Okakura Tenshin: “Skepticism” as “Revival"), Chöiki bunka kagaku kiyõ (Interdisciplinary Cultural Studies), no. 13 (2008): 91-105; idem, “Asano Akira no Okak ura Tenshin ron: ‘Nihon roman-ha no shiihen-sha’ ni yoru hihyõ” (Asano Akira's Review of Okakura Tenshin: The Critique by a “Peripheral Member of the Japan Romantic School”), Hikaku bungaku kenk yu (Studies in Comparative Literature), no. 92 (November, 2008):

82-103.

14.

For a recent assessment of Okakura in this context, see the discussion and in- clusion of Okakura, in Pan-Asianism: A Documenta ry Histor y, Vo fume J: 1850-1920, ed. Sven Saaler and Christopher W. A. Szpilman (Lan- ham, Boulder, New York, Toronto, Plymouth UK: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc., 201 I ), 93-111.

15.

On Takeuchi Yoshimi, see Richard F. Calichman, Takeuchi Yoshimi. Dis- placing the West (Ithaca, NY: Cornell

University East Asia Program, 2004). 16.

See F. G. Note helfer, “On Ideal- ism and Realism in the Thought of Okakura Tenshin,” Journal of Japa- nese Studies 17, no. 2 (1990): 309-55; Stefan Tanaka, “Imaging History: Inscribing Belief in the Nation,” The Journal o/Asian Studies, vol. 53, no. 1 (Feb. 1994): 24-44.

17.

Satö Döshin, “Tenshin kenkyú no genjÔ to igi,” 44. Satõ also attributes the increase in Okakura-related events and publications in the 1960s and the 1970s to the sequence of commemo- rative occasions related to Okakura and the Japan Art Institute that took place during this period, such as the centennial of Okakura's birth in 1962. 18.

It is significant that it was Nivedita, not Okakura, who declared Asia to be “One,” with a capitalized “O,” at the end of her introduction to The Ideals of the East with the following statement: “Asia, the Great Mother, is for ever One.” Nivedita, introduction to Kakuzo Okakura, The Ideals of the East with Special Reference to the Art of Japon (London: John Murray, 1905). xxii. At the end of the handwritten manuscript that Okakura penned while in India (generally known today as The Awakenin8 •fthe

East), Nivedita again wrote, “Asia is

One.” This is crossed out and Okakura instead wrote, “We are one”; see Okakura Tenshin, Okakura Tenshin zenshïi, vol.1 (Tokyo: Heibonsha, 1980), 482. These instances suggest that Okakura’s interest in soliciting political unity among Asians was inspired largely by Nivedita and her Be n gali associates, but their relationship soured while Okakura was in India and he did not appear to becomminedłothiscausebeyondhis Indian sojourn and especially after his failed attempt to organize a parliament of Asian religions to take place in

Japan in 1903. See Noriko Murai, Tenshin and Fenollosa,” in A I-History “Authoring the East: Okakura Kakuzö of Modern Japanese Aesthetics, and the Representations of East Asian ed. Michael Marra (Honolul u: Art in the Early Twentieth Century” University of Hawaii Press, 2001), (Ph.D. diss., Harvard University. 43-53; Michele Marra, “Hegelian 2003), 72-73, 91-92. Reversal: Okakura Kakuzö,” in

19. Modern Japanese Aesthetics : A On this issue, see Karatani Köjin, Reader (Honolulu: University of “Japan as Art Museum: Okakura Hawaii Press, 1999), 65-71.

20.

As far as we know. the only other English translation of Okakura’s Japanese writings is “A Lecture to the Painting Appreciation Society [Kangakai]” ( 1 879), included in Michele Marra, Modern Japanese Aesthetics, 71-78.

2023/03/25

숙흥야매 - 나무위키

숙흥야매

최근 수정 시각: 2022-01-15

분류 고사성어

한자어: 夙興夜寐

간자체 : 夙兴夜寐

한자 훈음: 일찍 숙 · 일어날 흥 · 밤 야 · 잠잘 매

영어: working early and late

1. 겉 뜻2. 속 뜻3. 출전4. 유래

1. 겉 뜻[편집]

아침에 일찍 일어나고 밤에는 늦게 잔다.

2. 속 뜻[편집]

책임을 다하기 위해 애쓰고 노력하는 모습을 비유하는 말

3. 출전[편집]

사마천 사기, 수서 수문제, 시경, 명심보감, 사자소학, 이황의 성학십도

4. 유래[편집]

1. 詩經 衛風 氓(시경 위풍 맹) 편에,

三歲爲婦 (삼세위부) : 삼 년 동안 그이의 부인이 되어

靡室勞矣 (미실로의) : 방에서 쉬임없이 고생하였네.

夙興夜寐 (숙흥야매) : 새벽에 일어나 밤늦게 잠들며

靡有朝矣 (미유조의) : 아침이 있는 줄도 몰랐네.

言旣遂矣 (언기수의) : 혼인의 언약이 이루어지자마자

至于暴矣 (지우포의) : 남편은 갑자기 난폭하게 나를 대했지.

兄弟不知 (형제부지) : 형제들도 이를 알지 못하고

咥其笑矣 (희기소의) : 나를 보면 그저 허허 웃기만 하네.

靜言思之 (정언사지) : 가만히 앉아 돌이켜 생각해 보니

窮者悼矣 (궁자도의) : 나 자신만 가여워지는구나.

2. 詩經 小雅 小宛(시경 소아 소완) 편에,

題彼脊令 (제피척령) : 날아가는 할미새를 보니

載飛載鳴 (재비재명) : 날면서 울어 대네.

我日斯邁 (아일사매) : 나는 나날이 힘을 쓰고

而月斯征 (이월사정) : 달을 따라 노력하여.

夙興夜寐 (숙흥야매) : 새벽에 일어나 밤늦게 잠이 들며

無添爾所生(무첨이소생) : 낳아주신 부모님 욕되게 말아야지.

3. 明心寶鑑 存心(명심보감 존심) 편에,

夙興夜寐 所思忠孝者 人不知天必知之(숙흥야매 소사충효자 인부지 천필지지)

(아침에 일어나 밤늦게까지 충효를 다하는 자는 사람이 알아주지 않아도 하늘이 반드시 알아줄 것이다.)

4. 사기 전한 효문제

"상(효문제)는 아침 일찍 일어나서 나랏일을 돌보고 밤 늦게되어야 겨우 잤다."

===

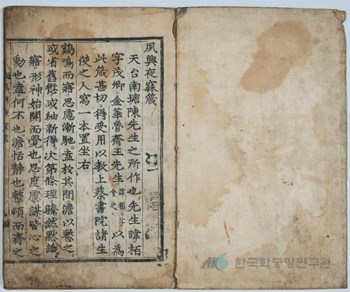

숙흥야매잠주해 (夙興夜寐箴註解)

숙흥야매잠 권수

유교

문헌

조선전기 학자 노수신이 송나라 진백의 「숙흥야매잠」을 분장하고 해석하여 1568년에 간행한 주석서.

==

접기/펼치기정의

조선전기 학자 노수신이 송나라 진백의 「숙흥야매잠」을 분장하고 해석하여 1568년에 간행한 주석서.

접기/펼치기편찬/발간 경위

이 책은 『노소재시강록(盧穌齋侍講錄)』과 함께 저자가 진도에서 유배 생활을 하는 동안 지은 것이다. 책을 처음 완성한 것은 1554년(명종 9)경으로 그 초본을 이황(李滉)과 김인후(金麟厚)에게 보내 질정을 청하였고, 1560년에 다시 이황에게 편지를 보내 의견 교환을 통해 부분적인 수정을 거쳐 완성한 것이다.

그 뒤 1568년(선조 1) 저자가 충청도 관찰사로 있으면서 선조에게 상소문과 함께 올렸던 것을 왕명에 의해 교서관에서 간행하였다. 이후 간행본은 없어지고 필사본으로 전해지던 것을 1634년(인조 12) 승려인 두섬(杜暹)이 사재로 옥천암(玉泉庵)에서 중간하였다. 다시 1746년(영조 22) 왕명에 의해 황경원(黃景源)이 쓴 영조의 어제 서문과 이황의 『성학십도(聖學十圖)』 가운데 제10도인 「숙흥야매잠도」를 첨부하여 세 번째로 간행하였다.

접기/펼치기서지적 사항

1책. 목판본. 규장각 도서 등에 있다.

접기/펼치기내용

[‘숙흥야매’라는 말은 『시경』 소아(小雅) 소완편(小宛篇)의 구절에서 따온 것으로,

이에 대해 저자는 심학(心學)의 입장에서 전체 26구절을 8장으로 나누고, 각 장마다 먼저 훈고(訓詁)를 곁들인 주석을 달고, 다시 그 장의 주요한 의미를 해설하고 있다.

이 저술보다 약간 뒤에 이루어진 이황의 주저인 『성학십도』의 「숙흥야매잠도」는 이 책과 약간 차이점을 보이고 있지만, 이 책의 영향을 받고 있는 것으로 보인다. 뒤에 장복추(張福樞)가 이 두 책을 참조해 『숙흥야매잠집』을 저술하였다.

접기/펼치기의의와 평가

조선조 성리학의 발달 과정과 특색을 드러내는 저술이다.

접기/펼치기참고문헌

『퇴계전서(退溪全書)』

『하서집(河西集)』

강주영 | 최봉영 선생의 "영성이 무엇이냐?"

===

===

===

===

===

===

===

박성용 막:9:1-29 길가는 자의 정체성

최봉영 - 이뭣고=이+무엇+고 , "영성이 무엇이냐?"

2023/03/24

God concept: Chamunda, goddess of cremation : Smite

Reading the Qur'an as a Quaker

Reading the Qur’an as a Quaker

April 26, 2018

Quaker author Michael Birkel felt that we aren’t hearing the whole truth about Islam, so he went out to discover it for himself.

Thanks to this week’s sponsor:

Everence helps people and organizations live out their values and mission through faith-rooted financial services. Learn more.

Transcript:

There is within Islam a sacred saying called a “hadith,” in which God is speaking and God says, “I was a hidden treasure and I desired to be known.” This was one of the motivations of the act of creation itself. “I was a hidden treasure and I desired to be known.” If that desire— that deep desire—is imprinted on the very fabric of the universe, then our coming to know one another across religious boundaries is a sacred task and a holy opportunity.

Reading the Qur’an as a Quaker

We Quakers have a commitment—we call it a testimony—to truth telling. And it was pretty obvious to me that not the whole truth was being told about Islam or about Muslims. In the media we would hear about extremists who live far away and never hear about our Muslim neighbors who live here: what do they think?

Conversations About the Qur’an

So I traveled among Muslims who live from Boston to California, and I just had one question for them: would you please choose a passage in your holy book and talk to me about it? The result was a series of precious conversations, because what they brought to the conversation was their love for their faith, for God and for the experience they had of encountering God’s revelation through the Qur’an.

The Experience of Reading the Qur’an

One of my Muslim teachers told me, when I asked him, “what is it like to read the Qur’an?” and he said it’s this experience of overwhelming divine compassion. You feel yourself swept up into this divine presence where you feel so loved that nothing else matters. Any other desires you had in the world just disappear. You are where you want to be. At the same time, you feel this overwhelming sense of compassion for others. And he told me if you don’t feel that, you’re not reading the Qur’an.

A Diversity of Voices

I spoke with Muslims from many places that are within the spectrum of the Islamic community. I spoke to Sunnis, I spoke to Shiites, I spoke to Sufis, I spoke to men, I spoke to women. I spoke to people of many ethnic heritages. If there’s one thing I learned, it is that whatever you think Islam is, it’s wider than that.

One imam—who was by 39 generations removed a descendant of the prophet Muhammad himself—spoke to me and said that for him, one of the jewels of the Qur’an was this notion that you do not repel evil with evil. You drive away evil with goodness. And if you drive away evil with good, then you find that the person whom you regarded as your enemy can become your friend.

Another Muslim teacher taught me that according to the Qur’an, when we hear about good and evil, our task is not to divide the world into two teams—here are the good guys, here are the bad guys—but rather, our inclination towards evil is found in every heart and that is where the fundamental conflict resides. This to me sounded very close to the message of early Quakers.

Encountering the Qur’an as a Non-Muslim

I believe that for a non-Muslim, encountering the Qur’an for the first time might be perplexing. You might imagine being parachuted down into the book of Jeremiah. There you land: you don’t know the territory, here are these prophetic utterances (which is how Muslims see the Qur’an) and in Jeremiah they don’t always have names attached to them. They’re not in chronological order and they’re not thematically arranged. I believe the Qur’an can read like that to a newcomer. That’s why I think it’s valuable to read it in the company of persons who have been reading it their whole lives.

What is it like to read someone else’s scripture? I think it’s quite possible that it can change you in ways that I can’t predict for any reader, except to say that it will make your life richer. It will make your life better to know this. I am not a trained scholar of Islam. I did some preparation for this project, but mostly what I did was go out and talk to my neighbors, and it changed my life. And so I would like to encourage anyone who’s hearing these words to go out, cross religious boundaries, talk to their neighbors, because your life will be changed too.

Discussion Questions:

- Have you connected with someone across religious boundaries? How were you changed by the experience?

- Michael Birkel says that the Quaker commitment to truth telling inspired him to travel the country having conversations with Muslims in those areas. If you could embark on a similar project, what topic would you pick? How would you go about it?

The views expressed in this video are of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect the views of Friends Journal or its collaborators.

2023/03/23

신라인도 유학 갔던 불교의 성지, 인도 날란다 - 오마이뉴스

신라인도 유학 갔던 불교의 성지, 인도 날란다

23.03.23

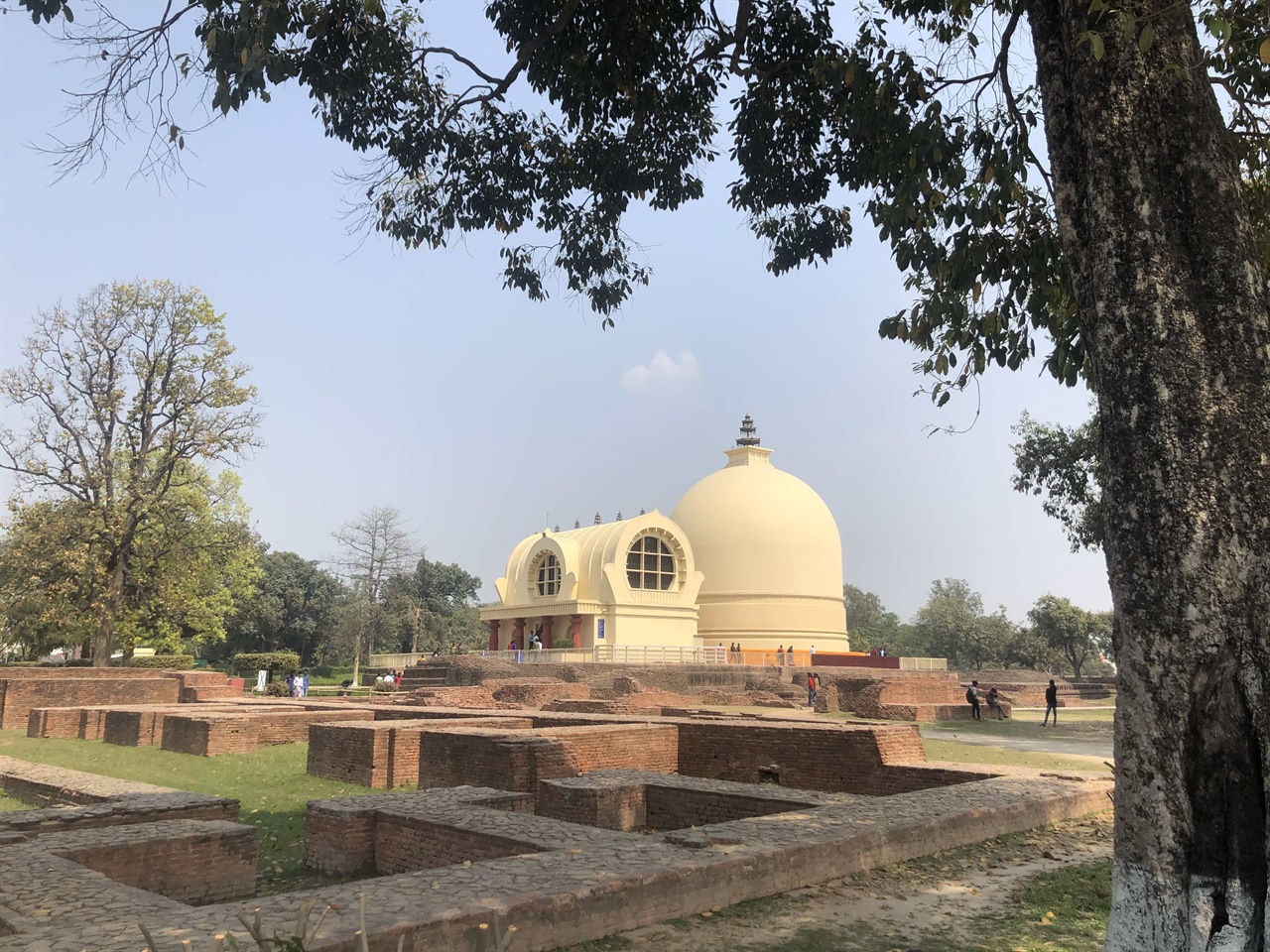

김찬호(widerstand365)

석가모니가 깨달음을 얻었다는 보드가야를 들른 뒤에도, 저는 불교 성치를 찾아 여행을 계속했습니다. 일반적이라면 석가모니가 돌아가신 쿠쉬나가르(Kushinagar)로 향하는 게 맞겠지만, 저는 잠시 파트나(Patna)에 들렸습니다.

파트나에서 기차를 타고 외곽으로 나오면 '날란다(Nalanda)'라는 마을에 갈 수 있습니다. 이곳에는 과거 인도의 불교 대학, 날란다 대승원의 유적이 남아 있죠. 날란다 대승원은 당나라의 현장대사나 의정대사를 비롯해 신라의 유학승도 여럿 수학했던 공간입니다. 인도 불교의 전성기를 만들어냈던 현장이지요.

날란다 대승원은 12세기까지 존속하다가, 인도에 이슬람 왕조가 들어서며 파괴됩니다. 이미 인도 내에서는 불교의 세력이 약화되고 있었죠. 날란다 대승원의 파괴는 인도 불교의 종언과도 같은 사건이었습니다. 지금 날란다 대승원은 파괴된 유적으로만 그 흔적을 찾을 수 있습니다.

관련사진보기

제가 날란다 대승원에 들른 것 역시, 인도 불교의 전성기와 최후를 함께한 현장을 보기 위해서였습니다. 파괴되었지만 여전히 장엄한 유적을 둘러보았습니다. 이제는 무너진 벽과 토대만 남아 있지만, 그 규모를 충분히 상상할 수 있었습니다.

날란다에서는 라즈기르로 향하는 합승 지프가 운행되고 있었습니다. 하지만 차 안은 물론 위에까지 사람이 가득 탄 지프를 탈 수는 없겠더군요. 어쩔 수 없이 값은 좀 나가겠지만 오토릭샤를 불러 움직이려는 찰나, 저쪽에서 저처럼 오토릭샤를 찾고 있는 스님 두 분이 눈에 띄었습니다.

낯선 사람에게 잘 다가가지 않는 저인데도, 순간 말을 붙였습니다. 역시나 라즈기르로 향한다는 스님들은 방글라데시에서 오신 분들이셨습니다. 함께 가시는 게 어떠냐고 물었고, 저와 스님들은 잠시 이야기를 나누다 곧 지나가던 차 한 대에 함께 올라탔습니다.

스님들의 목적지는 라즈기르의 방글라데시 사원이었습니다. 보드가야에서와 마찬가지로, 이곳에서도 순례자들을 위한 숙소를 마련해 두고 있는 모양이더군요. 스님들은 저에게 절의 숙소를 내어 주시려 했지만, 저는 이미 파트나의 숙소에 짐을 풀어둔 터라 사양했습니다. 사원의 불상 앞에 잠시 앉아 있다 나오면서도 그게 못내 아쉽더군요.

▲ 라즈기르의 방글라데시 사원

ⓒ Widerstand

관련사진보기

덕분에 무사히 라즈기르를 거쳐 파트나로 돌아온 뒤, 다음 향한 도시는 고락푸르(Gorakpur)였습니다. 일반적으로 이 도시는 바라나시를 비롯한 지역에서 네팔로 넘어갈 때 들르는 관문 도시지요. 하지만 여기서 로컬 버스를 타고 1시간 30분 정도를 달리면 쿠쉬나가르에 갈 수 있습니다.

생각해보면 인도에서 버스라는 걸 제대로 타 보는 게 처음이었습니다. 버스 터미널이라는 곳도 처음 들려봤습니다. 예상은 했지만 역시나 혼란 그 자체더군요. 정해지지 않은 플랫폼과 알 수 없는 목적지의 버스들, 그리고 곳곳에서 큰 소리로 울리는 경적 소리. 버스 안을 돌아다니는 상인들과, 버스 하나 타는 데 뭐가 그리 복잡한지 싸우고 있는 사람들.

하지만 그 와중에도 타야 할 버스를 찾는 외국인의 질문을 무시하는 사람은 거의 없었습니다. 버스를 찾아 "쿠쉬나가르?"라는 질문을 몇 번이나 반복한 끝에 정차해 있는 어느 버스에 탑승했습니다. 처음에는 넉넉했던 버스 안에 사람들이 가득찰 무렵, 버스는 출발합니다.

▲ 쿠쉬나가르로 향하는 버스

ⓒ Widerstand

관련사진보기

옆 자리에 아들을 안고 앉아 있던 아버지는, 쿠쉬나가르에 도착할 즈음이 되자 제게 손짓을 합니다. 힌디에 약간의 영어가 섞여 있었지만, 무슨 뜻인지는 충분히 알아들을 수 있었습니다. "아까 표를 사고 받은 영수증을 차장에게 보여주면 거스름돈을 줄 거야. 그걸 받아서 저 앞에서 내리면 돼."

그러고보니 아까 표를 사고도 거스름돈을 받지 못했습니다. 몇 루피 되지 않는 돈이라 그냥 그러려니 했는데, 덕분에 거스름돈까지 받아 쿠쉬나가르에 무사히 내렸습니다. 가득한 승객에 답답했던 버스 안에서 벗어나니 고요한 마을이 눈에 들어옵니다.

부처님이 열반에 들었다는 쿠쉬나가르. 이곳 역시 여러 나라에서 만든 사원이 곳곳에 들어서 있습니다. 한켠의 넓은 공원 안에는 와불을 모신 열반당도 세워져 있죠. 작은 마을은 걸어서도 쉽게 돌아볼 수 있었습니다.

쿠쉬나가르는 작은 마을이라 따로 버스 터미널이 없습니다. 돌아올 때는 내린 곳의 맞은편 길가에 서 지나가는 버스를 잡아 타야 했죠. 마을을 나오니 다행히 버스를 기다리고 있는 현지인들이 여럿 서 있더군요. 그들 사이에 끼어 버스를 타고, 다시 고락푸르까지 무사히 돌아왔습니다.

▲ 쿠쉬나가르 열반당

ⓒ Widerstand

관련사진보기

보드가야에서 날란다와 라즈기르, 그리고 쿠쉬나가르까지. 여러 불교 성지를 생각보다는 빠르게 돌아본 편이었습니다. 큰 실수나 일정의 지연 없이, 여행자가 적은 동네를 무사히 돌아다녔습니다. 그리고 그 사이에는 물론 여러 사람들의 도움이 있었죠.

쿠쉬나가르에서 돌아오는 길, 석가모니의 마지막 말씀을 생각했습니다. 이미 자신이 열반할 날이 얼마 남지 않았다고 말한 석가모니는, 쿠쉬나가르에 도착해 숲에 가사를 깔고 누웠습니다. 이곳에서 마지막 가르침을 행한 석가모니는 "존재하는 모든 것은 변한다. 게으름 없이 정진하라"라는 말을 남기고 열반에 들었습니다.

"게으름 없이 정진하라." 불교 성지를 돌아보며 만난 여러 스님들을 생각했습니다. 그런 사람들의 게으름 없는 정진이 모여 지금까지 이어지고 있는 것이겠죠. 보드가야와 쿠쉬나가르에 있던 각국의 사원들도 그렇게 모여 만들어진 것이겠지요.

하지만 그러면서도, 이제는 결국 폐허가 되어버린 날란다의 모습도 생각했습니다. 그들의 정진은 어디로 간 것일까요. 날란다의 사원에서 수행했던 수많은 스님들 가운데, 지금 우리가 알 수 있는 이름은 극소수에 불과합니다. 한때 1만 명의 학생이 살고 있었다던 날란다에서, 그 나머지의 이름은 어디로 사라지고 없는 것일까요.

▲ 날란다 역

ⓒ Widerstand

관련사진보기

그들의 수행과 공덕이 무엇이 되어 남았을지, 저는 알지 못합니다. 날란다의 건물들처럼 무너지고 쓰러졌을지도 모를 일이지요. 지금 우리가 게으름 없이 정진하고 노력하더라도, 그 역시 언젠가 폐허가 되어 흔적조차 남지 않을지도 모르겠습니다.

그러나 단 한 가지, 그 폐허를 찾아가는 여행자에게 누군가가 베푼 호의만은 제게 남았습니다. 주변의 낯선 사람에게, 아무런 주저함 없이 선뜻 내밀던 도움만은 제게 남았습니다. 적어도 그 기억만큼은 무너지지 않고 제 안에서 살아있을 것이라 생각합니다.

"존재하는 모든 것은 변한다. 게으름 없이 정진하라." 무엇을 향해 정진해야, 다른 '존재하는 것'들과는 달리 무너지지 않을 수 있을까요. 어쩌면 이 여행을 통해, 저는 제 나름의 답을 조금씩 찾아가는 중인지도 모르겠습니다.

덧붙이는 글 | 본 기사는 개인 블로그, <기록되지 못한 이들을 위한 기억, 채널 비더슈탄트>에 동시 게재됩니다.