Framework for Considering Productive Aging and Work

Older Age Structure of the Workforce

The aging of the U.S. population has contributed to profound changes in its workforce and society in general. This demo graphic transition involves movement in population distribution, with increased distribution toward the older ages.1–4 Over time, the movement has shifted from higher fertility rates among population segments who were having more children (and at an earlier age) and older segments with higher mortality due to lower longevity. The movement gradually transitioned to lower fertility rates among individuals having fewer children (and having them later in life). Mortality rates among older individuals also decreased, resulting in increased longevity. Consequently, the classic population pyramid shape of the early 20th century is giving way to a barrel shape, a demographic “rectangularization” due to decreased fertility and mortality, and increased life expectancy. Researchers expect that the number of people at older ages and younger ages will be similar by 2050 (Fig. 1).5–7 This is not likely to bea transitory effect; rather, it may be the new form of population distribution—one not seen before in human history.5,8 The impact of this demographic transition is that by 2022, about one-third (31.9%) of Americans aged 65 to 74 years will still be working.9 This is compared with 20.4% in 2002.9 Moreover, in developed and many developing countries, the dependency ratios (the ratio of unemployed to employed people) will rise and consequently fewer workers will be available to contribute to the overall support of older nonworkers. The many implications of a higher dependency ratio include a negative impact on tax revenue, growth, savings, consumption, and pensions.10

Longer Working Life

Because people are living longer and sometimes working longer, there is an increasing disparity between life expectancy and the age of retirement.5 Workers may have multiple motivations for staying in the workforce.11,12 Those who prefer to work longer do so because they are healthy enough and enjoy a sense of purpose and satisfaction. Those who must work longer do so generally because of inadequate savings.12 Other factors that prolong working life are rising dependency ratios, and higher ages of eligibility for public pensions and mandated retirement. In addition, fewer private employers now offer defined-benefit programs—traditional retirement or pension plans—that are sufficient to cover health care and living expenses over time.11,12 Regardless, those who work longer must endure the effects of aging as it relates to work, and the challenge for their employers and society is to keep them safe, healthy, and productive.

The impact of longer working life on workers can be significant in both positive and negative ways, likely depending on the type of work and the individual workers and worksites. On the positive side, work is the main means of income for consumption and savings, serves an anchoring function in society, and can be a source of dignity and purpose.5 Part of this sense of purpose can be the ability to contribute meaningfully to one’s organization and community. Negative consequences of working longer may include increased morbidity and mortality from injuries, longer recovery times, burnout, job lock, age discrimination, job insecurity, periods of unwanted unemployment, and less nonwork time.13

The productivity of the older workforce has been questioned.14,15 Although the literature provides differing views, there is little empirical evidence that older workers are less productive.16–18 A 2012 Institute of Medicine review of the literature on macroeconomic effects of the aging U.S. population concluded that any influence on productivity was likely to be negligible, but it called for further research on the topic.19 Recently, a national study of the period 1980 to 2010 in all 50 states found that a 10% increase in the fraction of the population greater than 60 years of age translated into a decreased gross domestic product (GDP) growth rate of 5.5% per capita. Maestas et al17 observed: “Two thirds of the reduction is due to slower growth in the labor productivity of workers across the age distribution, while one third arises from slow labor force growth.” The reduction in productivity is across all age groups, in part because older workers are the most knowledgeable, and when they retire the overall productivity of the remaining workforce suffers.17

Within the context of work, aging should not be considered in a vacuum. The ability to age successfully or productively intersects with factors such as socioeconomic status (SES), which is an important predictor of morbidity and mortality outcomes. SES—a composite of education, income, and occupational status—contributes to variances in lifestyle risk factors, access to health care, psychosocial factors, and other living conditions.20 In addition, work environment is linked with these variances and is an important factor to consider when studying such relationships. A recent meta analysis of 48 studies comprising 1.7 million people across the United States, France, United Kingdom, Switzerland, Portugal, Australia, and Italy found that lower SES is associated with a reduction in life expectancy of over 2 years, on par with being physically inactive.21 It is important to note that although this and other similar studies tend to uncover similar associations between SES and longevity, disparities due to social, policy, economic, and political differences are noted across countries.22,23 All of these disparities also have implications for work. As individuals live longer and work longer, the effects that SES may have on productive aging and work are apparent, particularly with respect to more high-risk work environments and conditions that already put workers at risk for early mortality.

Given the aforementioned implications, there is a need to understand the issues of longer working life in the United States. The National Research Council in 2004 concluded that investigators should examine assumptions about aging, health, work, and retirement.24 The concept of chronobiological thresholds of aging is arbitrary and differs among individuals.25 (Chronobiological refers to the health effects of time on biology, particularly cyclic phenomena.) However, physical and cognitive changes over the life span generally but variably manifest as age-related declines in function and health.24 Health is not a fixed state; therefore, health care management needs to address specific health issues at different ages.26

What is more, an individual’s working life no longer traditionally consists of one full-time job with one employer. Many forms of employment now exist: nonstandard, precarious, contingent, seasonal, temporary, and contractual.27,28 These new forms may alter the common progression from childhood education to adult career to retirement near age 65. Work has increasingly become a dynamic pool of activities with blurred exits and various re-entries. The norm now is becoming a blended life of work, education, leisure, and nonwork, intermingled. Moreover, retirement is a process that may unfold over time and occur heterogeneously.29

METHODS

The framework for productive aging at work was built on the research of Butler and Gleason (1985)30 and that of Rowe and Kahn (1997)31 on successful aging, as well as the workability concepts developed by Ilmarinen (1999)32 and others. Productive aging promoted that older people could be vital and active contributors to their work, family, and community and engage in productive behaviors in later life activities, including paid and volunteer work, continuing education, housework, and caregiving. In response to the growing aging population and the growing evidence on productive aging, in 2015, the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) established the National Center for Productive Aging and Work (NCPAW). The authors are principal members of the NCPAW. The NCPAW developed a four-element conceptual framework for productive aging that could be applied to work: 1) a life span perspective; 2) a comprehensive, integrated approach to occupational safety and health; 3) emphasis on positive outcomes for both workers and organizations; and 4) a supportive culture for multigenerational issues.33 The purpose of this paper is to identify literature to substantiate and enhance this conceptual framework. A snowball literature review approach was used.34 The authors first conducted a forward snowball approach, which began with the work of Butler and Gleason30 and Rowe and Kahn31 and Ilmarinen.32 The authors then conducted a backward snowball approach, which began with the work of Fisher et al,18 Zacher,35 and Berkman et al.5 Further, a search was performed using key terms in the four elements of the framework as well as the terms “productive aging” and “successful aging.”

The terms “productive aging” and “successful aging” have different but overlapping interpretations. Rowe and Kahn31 define successful aging as “growing old with good health, strength, and vitality.” Productive aging espouses similar concepts but places them within the context of work.30,36 Using this strategy, relevant literature for each element was assessed and discussed in this paper.

APPROACHES TO ADDRESSING THE AGING WORKFORCE

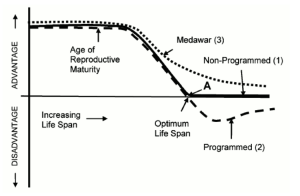

The various paradigms for considering aging provide context for the working-life perspective. Traditionally, gerontology has focused on the frailties and limitations associated with advanced years, with theories emphasizing the inevitable decline of human capacity.37 Building on a commonly held assumption of physical and mental decline as a normal feature of aging, various scholars advanced disengagement theory, which emphasizes the inevitability of decline with increasing age and decreasing activity and involvement.37–39 Another approach—the SOC model—advocates the use of three processes to manage this reduction: Selection, Optimization, and Compensation.40 This model calls for adjustments to accommodate decrements brought about by aging.

In the latter part of the 20th century, there was a gradual, fundamental transition from theories emphasizing the inevitable decline of human capacity to concepts stressing a positive, multidimensional view of aging.37 This expanded view considers both the challenges and opportunities that come with aging.41 As Johnson and Mutchler37 observed, “Important theoretical changes in the conceptualization of the aging process, coupled with the publication of empirical work documenting viability, strength, and contributions of older adults, resulted in the emergence of the multiple positive perspectives on aging.”

One such conceptualization was “successful aging.” An early definition described successful aging as the experience of joy, happiness, and satisfaction later in life.42 The more recent use of the term builds on the work of Rowe and Kahn,31 which identifies successful aging as occurring at the intersection of good health, high physical and cognitive function, and active involvement in social activities.37 Rowe and Kahn31 distinguish successful aging from usual aging on the basis of those characteristics. There have been many definitions of successful aging and research on predictors— Depp and Jeste43 identified 28 studies with 29 definitions. Most definitions were based on the absence of disability and, to a lesser extent, on the absence of cognitive impairment.43 “Increased longevity, rising human capital, and changing expectations altered the scholarly discourse on aging in the 1980’s,” Butler and Gleason noted, “and a new but related concept [of] ‘productive aging’ became a topic of investigation.”30

The scientific literature on productive aging describes numerous activities as indications of productive aging, including paid and unpaid work, assistance to others, and caregiving. The productive activity framework has been described as highly successful in identifying the social, cultural, and political choices that shape the activity of older adults.37 Productive aging encapsulates activities in and out of the labor market and addresses those that generate goods and services for which an individual may or may not be paid.36,44– 47 The key to productive aging is productive engagement, and research has shown that when older individuals direct their energies and talents toward identified private and public needs, they generate significant benefits for themselves, their families, and communities.44,45 The literature on productive aging also recognizes the importance of social, cultural, political, and institutional factors.46 This is important because the safety and health of the workplace are the employer’s responsibility; moreover, work related issues such as inflexible social structures, wage differentials, and role opportunities and norms can affect safety and health.47,48

n many ways, the concepts of successful aging and productive aging are related and complementary. However, whereas successful aging refers to physical, mental, and overall well-being in advanced age, productive aging is more closely tied to advocating for social policy and workplace changes for older workers.31,36,37,44 Nevertheless, useful concepts can be drawn from the successful aging literature as well. Building on earlier influential reviews,11,49,50 research on the role of age in the workplace has substantially increased in the early 21st century.35,51,52 Building on the work of Butler and Gleason30 and Rowe and Kahn,31 NCPAW identified productive aging in the context of work as the means of providing a safer and healthier work environment that enables workers of any age to function optimally and thrive.44 Placing increased focus on successful, productive aging at work is critical to responding to the demographic transition.35,52,53

FRAMEWORK FOR PRODUCTIVE AGING

Productive aging emphasizes the positive aspects of growing older—how individuals can make important contributions to their own lives, their communities, organizations, and society as a whole.30,31,36,44 In the context of work, productive aging is supported by a safe and healthy work environment that empowers workers to perform their jobs successfully and thrive at all ages. Productive aging pertains not only to the paid workforce but also to those who are volunteering, serving as family caretakers, and trying to remain independent and self-sufficient for as long as possible.54,55

As noted earlier, there are four elements of productive aging that can be applied to work:

(1) a life span perspective;

(2) a comprehensive and integrated approach to occupational safety and health;

(3) an emphasis on positive outcomes for both workers and organizations; and

(4) a supportive work culture for multigenerational issues (Fig. 2).

Element 1: A Lifespan Perspective

Productive aging reflects all the changes that occur over the course of life, influenced by genetic, epigenetic, environmental, and behavioral factors.24 Throughout life, various physical functions and features of the body change and generally decline, such as muscle mass (sarcopenia), grip strength, forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1), and bladder compliance.56–58 The nature of the decline differs widely among people. The rate of decline may also differ among workers, according to their jobs. A construction worker who is 40 years old may be physically “older” in many ways than an office worker who is 70 years old.18,35,59

Figure 3 illustrates the impact of early and late environmental exposures and elder health outcomes.26 The figure shows how organ exposures across the life span can bend life trajectories toward and across disability and disease thresholds. Focusing on an organ of particular concern with regard to aging, the brain, reveals that there are various pathways leading to brain or cognitive dysfunctions. Researchers are learning more about these distinctive pathways, and it is becoming clearer that genetic and environmental influences during life are contributing factors.18

Cognitive Changes

Recent research has shown that genetic and environmental factors throughout life can lead to loss of protein homeostasis, DNA damage, lysosomal dysfunction, epigenetic change, and immune dysregulation.60 These changes occur during aging, and “disease free brains, especially in the oldest old, are rare,” concludes Wyss-Coray who also notes “it is possible that normal aging forms a continuum with neurodegeneration and disease, and that stochastic factors, framed by a person’s genetics and environment, will dominate their brain eventually.”60 In other words, many people never develop any serious decline in their cognitive function; cognitive decline is variable.61 Cognitive decline is not inevitable. In some cases, it can be prevented or minimized through chronic disease (such as hypertension or diabetes) prevention and control.62,63 Some cases of cognitive decline are reversible (eg after resolution of depression, infections, medication side effects, or nutritional deficiencies).64,65 Fisher et al18 emphasized the importance of considering the intersection of aging, cognitive function, and work. Cognitive function refers to various mental abilities including thinking, reasoning, problem solving, learning, decision-making, and attention.18 From a psychometric perspective, cognitive functioning can be seen as having two major components: crystallized abilities and fluid abilities.14,18,66,67 Crystallized ability, the ability to use learned knowledge and experience, generally grows with age, whereas fluid ability, the ability to solve new problems, declines with age. Clearly, both components of cognitive function are generalizations that vary among individuals. It is also important to consider that cognitive decline may influence performance in safety-critical work. This relationship between cognitive decline and work safety is complex; because of the definition of safety-critical work, more research is needed to address it.68 However, as Fisher et al18 have concluded, “research evidence to date has found minimal differences in the job performance of older workers compared to young workers.”

Health and Social Influences

Specific to working life, the ability of future generations to work longer hinges on their education and health through life, the habits and activities they engage in, and the opportunities available.5 In segments of the population that are well-educated, have access to good medical care, and maintain higher levels of health throughout their lives, there is “compressed morbidity”—that is, persons live longer and live more years healthy.69,70 It is vital to consider that individuals who will be in their 60s and 70s in 2030 to 2050 are now in early and mid-adulthood.5,71,72 Berkman et al5 concluded that “their current health and social conditions are therefore shaping their capacity and opportunities for employment options they will have at age sixty, seventy, or eighty.” Because the trajectories of work and retirement are shaped by the quality of education, there is a need for major institutions related to work organization and labor force participation to adapt in order to address the whole working-life continuum.5,47 Macroeconomic analyses indicate the importance of these factors.5 Given that fewer younger workers will enter the workforce in the coming decades, business enterprises will need to draw increasingly from the highly skilled and experienced older workforce.73 Enabling workers to extend their working life and continue to be productive in a safe and healthy manner requires a working-life continuum approach.

Working-Life Continuum

A useful conceptual model to account for life-change issues is the working-life continuum built on a life-course perspective.74–77 The working-life continuum includes the years of one’s life in work or employment, that is, from the first day on the job to postwork retirement. The central theme of the model is that it is comprehensive, accounts for periods across all ages, and considers the accumulation of effects. It is no longer the norm to have one or two jobs but rather a succession of jobs, with periods of work and nonwork (voluntary and involuntary) that can be characterized by stable and precarious work, under-and overemployment, and unemployment.28,77,78 Each of these new patterns can potentially be hazardous to workers’ health. For example, there is an association between temporary employment and psychological morbidity.79 Furthermore, it is well established that adverse health effects are cumulative over the working life and need to be targeted earlier for prevention or rehabilitation.24,70,80,81 However, how to measure cumulative risk is still an unresolved issue.81,82

Increasingly, researchers are finding promising solutions and avenues to help foster a safer and healthier working life for workers as they age.4,13,14,35,37,51,83 The occupational safety and health field and other disciplines that address the well-being of workers and enterprises could have more an effective impact if they focused on the whole working-life continuum.

As noted earlier, the lifespan perspective reflects the fact that biological, sociocultural, and cognitive influences throughout life can both help and hinder successful and productive aging.84–86 Therefore, aging is a concern not just for “older” workers but for workers of all ages. The influences of aging are relevant to all stages of the working life because aging can be characterized by plasticity—the extent an individual changes in response to experiences and the environment. Aging is biological (physical), psychological (individual), and social (relationships, status/role, etc), all at the same time. These characteristics interrelate in complex ways to affect how each person deals with aging (and working), as well as how society interacts with the aging process.76 The aging process involves patterns of change and transition. This process has implications for how individuals—as they age—do their jobs and make changes in their work to reduce the occupational risks associated with physical, cognitive, and sociocultural changes associated with age. It also has implications for how employers structure work processes to address the needs of aging workers.18

Element 2: Comprehensive, Integrated Approach to Occupational Safety and Health

To promote productive aging requires a comprehensive, integrated approach to occupational safety and health. This approach is illustrated by the Total Worker Health® (TWH®) concept, the definition of which has recently evolved as the integration of protection from work-related safety and health hazards with the promotion of injury and illness prevention efforts to advance worker well-being.87 TWH prioritizes these elements: a hazard-free work environment for all workers, including control of hazards and expo-sures; organization of work; built environment supports; leadership; compensation and benefits; community supports; changing work-force demographics; policy issues; and new employment patterns.82,87 TWH also integrates interventions that enhance workers’ safety, health, and well-being both on and off the job. For example, issues such as obesity and cardiovascular disease are less often considered to be unrelated to work, and programs that address these and other issues tend to benefit workers of all ages.87–89 TWH implies a holistic understanding of the factors associated with worker well being, and one of these factors is the aging process. Such a holistic approach accounts for the needs of workers in various job types (eg, traditional vs contingent employment) and considers the possibility that strategies used to enhance the well-being of permanent employees might not meet the needs of temporary workers.28

TWH is built on another comprehensive approach known as the “workability” concept, developed in Scandinavia in the 1980s.90 Workability refers to a worker’s capacity to perform his or her job, given available resources, and adequate working conditions.91 The Finnish government developed a policy instrument known as the Promotion and Maintenance of Workability that uses data from applying a workability scale to working populations.92 The various contributors (as assessed by R2 coefficient from various analyses) for work life expectancy include health (0.39), work environment (0.33), work organization (0.33), work-life balance (0.14), age management (0.13), and competence (0.13).90 Policy approaches are then designed to address all these contributors to working life expectancy.93

As one of the characteristics of the productive aging concept, a comprehensive and integrated approach also requires the use of a broad range of education and intervention strategies to enhance working life for all ages. For example, such strategies might vary according to whether the working conditions affect permanent workers or contingent workers. Education and intervention should also draw from academic disciplines and knowledge bases such as ergonomics, psychology, injury prevention, and health communication.94

Element 3: Emphasis on Positive Outcomes for Both Workers and Organizations

A productive aging at work approach requires attention to both the workers and the enterprise. The relationship between the two is interactive. Programs that address productive aging have to recognize both worker-centered outcomes and organization-centered outcomes.83 For the worker, these programs should address maintenance of physical and mental health, safety of the work environment, fair and respectful treatment, and ability of the worker to contribute to the organization while meeting needs outside work. For the organization, programs should result in decreased: health care costs; injuriy; disability and workers’ compensation costs; turnover; and absenteeism and presenteeism. These programs could also result in improvements in workforce and enterprise productivity; recruitment and retention of experienced workers; and transfer of experience between generations.95,96

The range of outcomes from these efforts might bring benefits to workers (such as safer work environments) but might also be in conflict with organizations’ short-term interests (eg, the extra costs associated with incorporating physical safety measures), or vice versa.97,98 Because changes in outcomes for one party affect the other, outcomes benefitting both workers and organizations need to be acknowledged and prioritized to enhance productive aging. The well-being of the workforce and the organization are inextricably linked.95,99 This relationship is intensified as the workforce ages and the prevalence of chronic diseases increases. The well-being of both the organization and employees can increase.99,100 Generally, the view of employers has been that employee health is a cost to be reduced rather than an asset that needs to be managed. As Loeppke et al95 concluded, “Integrating productivity data and health data can help employers develop effective workplace health, human capital, and investment strategies.”

Focusing on positive outcomes for workers and organizations can involve three major elements: (1) addressing chemical/physical/ biological and psychosocial hazards; (2) maintaining productivity; and (3) promoting well-being.

Hazards

Various hazards and the organization of work can have an adverse effect on workers. These hazards include chemicals (eg, lead, organic phosphates, solvents), physical agents (eg, noise; heat), and psychosocial hazards such as stress and the complexity of work. These all have been shown to have cognitive effects.101 As Grzywacz et al101 concluded: “A growing body of literature has demonstrated that cognitive decline lessens in situations when work is more complex, where complexity is the extent to which workers must make decisions with ambiguous or competing contingencies.” One study showed that job complexity was associated with better self-perceived memory in men and women and better episodic memory and executive function in women.101

Productivity

It is difficult to assess age–productivity relationships because of the fundamental challenge of what to consider. In addition, confounding issues in age distributions in a study population can lead to identifying incorrect associations between age and productivity. When robust data are used, such as by Ng and Feldman16 in the meta-analysis of 380 studies of the relationship between age and job performance, age was generally unrelated to core task performance. Crystallized cognitive abilities can be a comparative advantage for older workers in these types of jobs. For example, an assessment of age and productivity on an auto assembly line in Germany showed mean productivity rose from age 25 to age 65 years.72 The type of work often determines to what extent crystallized or fluid abilities are called upon.

Well-Being

The promotion of well-being of the workforce and the organization is a difficult and multifaceted challenge. The Finnish government specified lengthened working life, decreased accidents, and reduced physical and psychic strain as the means to promote well-being.92 Overall, in addressing well-being, there is a need to operationalize the concept and identify threats to and promoters of well-being. These may involve not only work-related but also nonwork-related factors.102 “Despite the need for further research on well-being, a body of knowledge known as macroergonomics may be useful to promote well-being at work.” Macroergonomics expands on traditional ergonomics of workstation and tool design, workspace arrangements, and physical environments.102–104 It also addresses the organization of work and the organizational structures, policies, and climates as upstream contributors to physical and mental health and well-being.

In addition, using person–environment fit models and adapting to person–environment misfit may contribute to well-being and to productive and successful aging at work.18,58,60 These indications of “fit” will most likely change over time and require modification of the job factors.35

Element 4: Supportive Culture for Multi-Generational Issues

The reality of contemporary workplaces is that it can consist of five cohorts or generations in the work-life continuum that may have different needs, preferences, values, and characteristics.105,106 The productive aging approach requires a supportive work culture for multiple generations, which will all have different values and learning styles.107 As Rudolph and Zacher noted,108 “generational differences can potentially stimulate mentoring relationships and lead to discussions of specific generational issues, which can help organizations build programs and policies that address the needs of all workers, regardless of age.” The working-life continuum is populated by a successive series of generations in the workplace. The five generations proceeding through the continuum have certain common attributes. Currently, these five generations include Traditionals (1922 to 1945), Baby Boomers (1946 to 1964), Gen X (1965 to 1980), Millennials (Gen Y) (1981 to 1990), and Gen Z (1991 to 2017).109–112 Cullen113 notes that the “members of these generations have different ways of looking at the world and consequently how they approach work.” In particular, workers from different age cohorts might differ in such characteristics as attitudes toward work and supervision, communication styles, safety habits, and training needs.108 Such differences might involve several factors illustrated in the working-life continuum, such as risks and hazards outside of work and type of employment. While there are age-related differences among workers, variations also exist within age cohorts. Relying on broad age categories in meeting the needs of aging workers can lead to programs, policies, and decisions based on oversimplification and inaccurate stereotypes.107,108 Moreover, worker outcomes such as increased productivity might be seen as characteristics of advanced age, but they also could be tied to length of time at a job or access to training.

Prejudicial attitudes and behaviors can have a large impact on the aging worker in multigenerational workforces. “Ageism,” or discriminatory practices against older workers, can minimize the productivity of those workers and, in fact, the entire work-force.114,115 In addition, although ageism has an impact on both men and women, women in the workplace may be more vulnerable to both ageism and sexism, which may have implications as to whether they can realize productive aging.116

An NRC study (2015) on workforce trends in the U.S. energy and mining industries provides useful guidance for addressing the multigenerational workforce.117 The study recommends the steps summarized in Table 1, which can be generalized to many work-places. These steps focus on providing information and guidance by different means to all generations.

TABLE 1.

Potential Generalizable Recommendations for Proactively Addressing a Multigenerational Workforce*

| Proactively Address Multigenerational Issues in the Workplace | Guidance |

|---|---|

| A minimum standard for training required for new employees | “Safety and health training, which is currently uneven across industries, is best if it meets a minimum standard for content and it is provided by trainers who are not only industry knowledgeable, but also trained in how to communicate effectively with a diverse workforce. Where not required by mandate, companies should consider providing training to all employees, describing common hazards and how to deal with them.” |

| Leadership training | “Companies should train supervisors and managers in how to lead a diverse workforce…(which) would include such things as effective communication, communicating across cultures, building multi-generations work teams, understanding adult learning styles, and motivating diverse work teams. Leadership training should also include topics such as risk management, development of safety cultures, and disaster management.” |

| Formal OSH knowledge transfer | “Companies should capture what experienced workers know before they leave the workforce and use it to train new generations. Capturing their stories on video and creating a virtual ‘wisdom library’ that can be used whenever needed would be an effective strategy.” |

| Coaching and mentoring | “Retaining older workers is a solid strategy for keeping knowledge and experience in the workplace, and companies could strive to retain valued older workers, who can serve as trainers and mentors to younger workers.” |

Focusing particular attention on workers entering the work-force is also important, because it can affect their entire working lives. Okun et al118 have designed an approach for developing life skills in the form of eight core competencies in work safety and health: (1) “Recognize that, while work has benefits, all workers can be injured, become sick, or even be killed on the job. Workers need to know how workplace risks can affect their lives and their families; (2) Recognize that work-related injuries and illnesses are predictable and can be prevented; (3) Identify hazards at work, evaluate the risks, and predict how workers can be injured or made sick; (4) Recognize how to prevent injury and illness, describe the best ways to address workplace hazards, and apply those concepts to specific workplace problems; (5) Identify emergencies at work and decide on the best ways to address them; (6) Recognize employers are responsible for—and workers have the right to—safe and healthy work. Workers also are responsible for keeping themselves and coworkers safe; (7) Find resources that help keep workers safe and healthy on the job; (8) Demonstrate how workers can communicate with others, including people in authority roles, to ask questions or report problems or concerns when they feel unsafe or threatened.” In addition, these competencies may prove useful to workers in nonstandard employment, such as temporary workers who move from job to job.118 As workers age, having these basic competencies may increase their chances of having a safe, healthy, and productive work life.

If there is a generational divide, one area that is important to all age groups, but particularly millennials, is work-life balance. Work-life balance has been defined as “a comfortable state of equilibrium (balance/content) achieved between an employee’s primary priorities of his or her employment position and his or her lifestyle.”119 Addressing work-life balance for all age groups can be a factor in increasing workforce productivity.120–122

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION

Meeting the needs of workers of all age groups, each with unique aging-related issues, with a productive aging approach can be accomplished by using a four-element framework that includes a life span perspective; a comprehensive, integrated approach to occupational safety and health; an emphasis on positive outcomes for both workers and organizations; and a supportive culture that encourages discussion and management of multigenerational issues. Moreover, because impacts that occur in early and middle life affect later years of life, there is a particular need to proactively address the early and mid-life threats to working in later life. The four elements of the productive aging framework provide a comprehensive approach aimed at increasing the productivity and well-being of workers at all ages, particularly at the older ages. The approach also illustrates how productive aging can manifest at various stages of the working-life continuum. Although the productive aging approach focuses mainly on the business or enterprise level, there is a great need for social, economic, and political policies that support or enhance the approach.37

Implementation of programs that promote productive aging as described here is a way society and employers can address the current and expanding demographic transition. However, although this paper provides enhanced foundational concepts, more work is needed on characterizing and developing specific practical aspects. Failure to take this kind of action could lead to major societal consequences in terms of decreased health, productivity, and well-being.5,14 Because it is still relatively early in the U.S. demographic transition, there is time for enterprise and societal interventions to address these preventable negative consequences.5 That said, employers, organizations, and other decision-makers need to begin now to create work environments that foster and maintain productive aging.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors would like to thank Drs Gwen Fisher, Phyliss Cummins, and Julianna McDonald for comments on earlier versions, and Amanda Keenan, Amanda Stammer, and Nikki Romero for assistance in graphics and processing.

Footnotes

This work was conducted as federal employment. The findings and conclusions of this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health.

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

1While “intergenerational” and “multigenerational” are terms some times used interchangeably in the literature, the authors focus on aging across rather than within generations and therefore speak to multigenerational issues.