Music theory

Music theory is the study of the practices and possibilities of music. The Oxford Companion to Music describes three interrelated uses of the term "music theory". The first is the "rudiments", that are needed to understand music notation (key signatures, time signatures, and rhythmic notation); the second is learning scholars' views on music from antiquity to the present; the third is a sub-topic of musicology that "seeks to define processes and general principles in music". The musicological approach to theory differs from music analysis "in that it takes as its starting-point not the individual work or performance but the fundamental materials from which it is built."[1]

Music theory is frequently concerned with describing how musicians and composers make music, including tuning systems and composition methods among other topics. Because of the ever-expanding conception of what constitutes music, a more inclusive definition could be the consideration of any sonic phenomena, including silence. This is not an absolute guideline, however; for example, the study of "music" in the Quadrivium liberal arts university curriculum, that was common in medieval Europe, was an abstract system of proportions that was carefully studied at a distance from actual musical practice.[n 1] But this medieval discipline became the basis for tuning systems in later centuries and is generally included in modern scholarship on the history of music theory.[n 2]

Music theory as a practical discipline encompasses the methods and concepts that composers and other musicians use in creating music. The development, preservation, and transmission of music theory in this sense may be found in oral and written music-making traditions, musical instruments, and other artifacts. For example, ancient instruments from prehistoric sites around the world reveal details about the music they produced and potentially something of the musical theory that might have been used by their makers. In ancient and living cultures around the world, the deep and long roots of music theory are visible in instruments, oral traditions, and current music-making. Many cultures have also considered music theory in more formal ways such as written treatises and music notation. Practical and scholarly traditions overlap, as many practical treatises about music place themselves within a tradition of other treatises, which are cited regularly just as scholarly writing cites earlier research.

In modern academia, music theory is a subfield of musicology, the wider study of musical cultures and history. Etymologically, music theory, is an act of contemplation of music, from the Greek word θεωρία, meaning a looking at, a viewing; a contemplation, speculation, theory; a sight, a spectacle.[3] As such, it is often concerned with abstract musical aspects such as tuning and tonal systems, scales, consonance and dissonance, and rhythmic relationships. In addition, there is also a body of theory concerning practical aspects, such as the creation or the performance of music, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation, and electronic sound production.[4] A person who researches or teaches music theory is a music theorist. University study, typically to the MA or PhD level, is required to teach as a tenure-track music theorist in a US or Canadian university. Methods of analysis include mathematics, graphic analysis, and especially analysis enabled by western music notation. Comparative, descriptive, statistical, and other methods are also used. Music theory textbooks, especially in the United States of America, often include elements of musical acoustics, considerations of musical notation, and techniques of tonal composition (harmony and counterpoint), among other topics.

History[edit]

Prehistory[edit]

Preserved prehistoric instruments, artifacts, and later depictions of performance in artworks can give clues to the structure of pitch systems in prehistoric cultures. See for instance Paleolithic flutes, Gǔdí, and Anasazi flute.

Antiquity[edit]

Mesopotamia[edit]

Several surviving Sumerian and Akkadian clay tablets include musical information of a theoretical nature, mainly lists of intervals and tunings.[5] The scholar Sam Mirelman reports that the earliest of these texts dates from before 1500 BCE, a millennium earlier than surviving evidence from any other culture of comparable musical thought. Further, "All the Mesopotamian texts [about music] are united by the use of a terminology for music that, according to the approximate dating of the texts, was in use for over 1,000 years."[6]

China[edit]

Much of Chinese music history and theory remains unclear.[7]

Chinese theory starts from numbers, the main musical numbers being twelve, five and eight. Twelve refers to the number of pitches on which the scales can be constructed. The Lüshi chunqiu from about 239 BCE recalls the legend of Ling Lun. On order of the Yellow Emperor, Ling Lun collected twelve bamboo lengths with thick and even nodes. Blowing on one of these like a pipe, he found its sound agreeable and named it huangzhong, the "Yellow Bell." He then heard phoenixes singing. The male and female phoenix each sang six tones. Ling Lun cut his bamboo pipes to match the pitches of the phoenixes, producing twelve pitch pipes in two sets: six from the male phoenix and six from the female: these were called the lülü or later the shierlü.[8]

India[edit]

The Samaveda and Yajurveda (c. 1200 – 1000 BCE) are among the earliest testimonies of Indian music, but they contain no theory properly speaking. The Natya Shastra, written between 200 BCE to 200 CE, discusses intervals (Śrutis), scales (Grāmas), consonances and dissonances, classes of melodic structure (Mūrchanās, modes?), melodic types (Jātis), instruments, etc.[9]

Greece[edit]

Early preserved Greek writings on music theory include two types of works:[10]

- technical manuals describing the Greek musical system including notation, scales, consonance and dissonance, rhythm, and types of musical compositions

- treatises on the way in which music reveals universal patterns of order leading to the highest levels of knowledge and understanding.

Several names of theorists are known before these works, including Pythagoras (c. 570 – c. 495 BCE), Philolaus (c. 470 – c. 385 BCE), Archytas (428–347 BCE), and others.

Works of the first type (technical manuals) include

- Anonymous (erroneously attributed to Euclid) Division of the Canon, Κατατομή κανόνος, 4th–3rd century BCE.[11]

- Theon of Smyrna, On Mathematics Useful for the Understanding of Plato, Τωv κατά τό μαθηματικόν χρησίμων είς τήν Πλάτωνος άνάγνωσις, 115–140 CE.

- Nicomachus of Gerasa, Manual of Harmonics, Άρμονικόν έγχειρίδιον, 100–150 CE

- Cleonides, Introduction to Harmonics, Είσαγωγή άρμονική, 2nd century CE.

- Gaudentius, Harmonic Introduction, Άρμονική είσαγωγή, 3d or 4th century CE.

- Bacchius Geron, Introduction to the Art of Music, Είσαγωγή τέχνης μουσικής, 4th century CE or later.

- Alypius, Introduction to Music, Είσαγωγή μουσική, 4th–5th century CE.

More philosophical treatises of the second type include

- Aristoxenus, Harmonic Elements, Άρμονικά στοιχεία, 375/360 – after 320 BCE.

- Aristoxenus, Rhythmic Elements, Ρυθμικά στοιχεία.

- Claudius Ptolemy, Harmonics, Άρμονικά, 127–148 CE.

- Porphyrius, On Ptolemy's Harmonics, Είς τά άρμονικά Πτολεμαίον ύπόμνημα, 232/3–c. 305 CE.

Post-classical[edit]

China[edit]

The pipa instrument carried with it a theory of musical modes that subsequently led to the Sui and Tang theory of 84 musical modes.[7]

Arabic countries / Persian countries[edit]

Medieval Arabic music theorists include:[n 3]

- Abū Yūsuf Ya'qūb al-Kindi († Bagdad, 873 CE), who uses the first twelve letters of the alphabet to describe the twelve frets on five strings of the oud, producing a chromatic scale of 25 degrees.[12]

- [Yaḥyā ibn] al-Munajjim (Baghdad, 856–912), author of Risāla fī al-mūsīqī ("Treatise on music", MS GB-Lbl Oriental 2361) which describes a Pythagorean tuning of the oud and a system of eight modes perhaps inspired by Ishaq al-Mawsili (767–850).[13]

- Abū n-Nașr Muḥammad al-Fārābi (Persia, 872? – Damas, 950 or 951 CE), author of Kitab al-Musiqa al-Kabir ("The Great Book of Music").[14]

- 'Ali ibn al-Husayn ul-Isfahānī (897–967), known as Abu al-Faraj al-Isfahani, author of Kitāb al-Aghānī ("The Book of Songs").

- Abū 'Alī al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAbd-Allāh ibn Sīnā, known as Avicenna (c. 980 – 1037), whose contribution to music theory consists mainly in Chapter 12 of the section on mathematics of his Kitab Al-Shifa ("The Book of Healing").[15]

- al-Ḥasan ibn Aḥmad ibn 'Ali al-Kātib, author of Kamāl adab al Ghinā' ("The Perfection of Musical Knowledge"), copied in 1225 (Istanbul, Topkapi Museum, Ms 1727).[16]

- Safi al-Din al-Urmawi (1216–1294 CE), author of the Kitabu al-Adwār ("Treatise of musical cycles") and ar-Risālah aš-Šarafiyyah ("Epistle to Šaraf").[17]

- Mubārak Šāh, commentator of Safi al-Din's Kitāb al-Adwār (British Museum, Ms 823).[18]

- Anon. LXI, Anonymous commentary on Safi al-Din's Kitāb al-Adwār.[19]

- Shams al-dῑn al-Saydᾱwῑ Al-Dhahabῑ (14th century CE (?)), music theorist. Author of Urjῡza fi'l-mῡsῑqᾱ ("A Didactic Poem on Music").[20]

Europe[edit]

The Latin treatise De institutione musica by the Roman philosopher Boethius (written c. 500, translated as Fundamentals of Music[2]) was a touchstone for other writings on music in medieval Europe. Boethius represented Classical authority on music during the Middle Ages, as the Greek writings on which he based his work were not read or translated by later Europeans until the 15th century.[21] This treatise carefully maintains distance from the actual practice of music, focusing mostly on the mathematical proportions involved in tuning systems and on the moral character of particular modes. Several centuries later, treatises began to appear which dealt with the actual composition of pieces of music in the plainchant tradition.[22] At the end of the ninth century, Hucbald worked towards more precise pitch notation for the neumes used to record plainchant.

Guido d'Arezzo' wrote in 1028 a letter to Michael of Pomposa, entitled Epistola de ignoto cantu,[23] in which he introduced the practice of using syllables to describe notes and intervals. This was the source of the hexachordal solmization that was to be used until the end of the Middle Ages. Guido also wrote about emotional qualities of the modes, the phrase structure of plainchant, the temporal meaning of the neumes, etc.; his chapters on polyphony "come closer to describing and illustrating real music than any previous account" in the Western tradition.[21]

During the thirteenth century, a new rhythm system called mensural notation grew out of an earlier, more limited method of notating rhythms in terms of fixed repetitive patterns, the so-called rhythmic modes, which were developed in France around 1200. An early form of mensural notation was first described and codified in the treatise Ars cantus mensurabilis ("The art of measured chant") by Franco of Cologne (c. 1280). Mensural notation used different note shapes to specify different durations, allowing scribes to capture rhythms which varied instead of repeating the same fixed pattern; it is a proportional notation, in the sense that each note value is equal to two or three times the shorter value, or half or a third of the longer value. This same notation, transformed through various extensions and improvements during the Renaissance, forms the basis for rhythmic notation in European classical music today.

Modern[edit]

Middle Eastern and Central Asian countries[edit]

- Bᾱqiyᾱ Nᾱyinῑ (Uzbekistan, 17th century CE), Uzbek author and music theorist. Author of Zamzama e wahdat-i-mῡsῑqῑ ("The Chanting of Unity in Music").[20]

- Baron Francois Rodolphe d'Erlanger (Tunis, Tunisia, 1910–1932 CE), French musicologist. Author of La musique arabe and Ta'rῑkh al-mῡsῑqᾱ al-arabiyya wa-usῡluha wa-tatawwurᾱtuha ("A History of Arabian Music, its principles and its Development")

D'Erlanger divulges that the Arabic music scale is derived from the Greek music scale, and that Arabic music is connected to certain features of Arabic culture, such as astrology.[20]

Europe[edit]

- Renaissance

- Baroque

- 1750–1900

- As Western musical influence spread throughout the world in the 1800s, musicians adopted Western theory as an international standard—but other theoretical traditions in both textual and oral traditions remain in use. For example, the long and rich musical traditions unique to ancient and current cultures of Africa are primarily oral, but describe specific forms, genres, performance practices, tunings, and other aspects of music theory.[24][25]

- Sacred harp music uses a different kind of scale and theory in practice. The music focuses on the solfege "fa, sol, la" on the music scale. Sacred Harp also employs a different notation involving "shape notes", or notes that are shaped to correspond to a certain solfege syllable on the music scale. Sacred Harp music and its music theory originated with Reverend Thomas Symmes in 1720, where he developed a system for "singing by note" to help his church members with note accuracy.[26]

Contemporary[edit]

Fundamentals of music[edit]

Music is composed of aural phenomena; "music theory" considers how those phenomena apply in music. Music theory considers melody, rhythm, counterpoint, harmony, form, tonal systems, scales, tuning, intervals, consonance, dissonance, durational proportions, the acoustics of pitch systems, composition, performance, orchestration, ornamentation, improvisation, electronic sound production, etc.[27]

Pitch[edit]

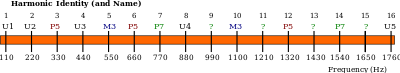

Pitch is the lowness or highness of a tone, for example the difference between middle C and a higher C. The frequency of the sound waves producing a pitch can be measured precisely, but the perception of pitch is more complex because single notes from natural sources are usually a complex mix of many frequencies. Accordingly, theorists often describe pitch as a subjective sensation rather than an objective measurement of sound.[28]

Specific frequencies are often assigned letter names. Today most orchestras assign concert A (the A above middle C on the piano) to the frequency of 440 Hz. This assignment is somewhat arbitrary; for example, in 1859 France, the same A was tuned to 435 Hz. Such differences can have a noticeable effect on the timbre of instruments and other phenomena. Thus, in historically informed performance of older music, tuning is often set to match the tuning used in the period when it was written. Additionally, many cultures do not attempt to standardize pitch, often considering that it should be allowed to vary depending on genre, style, mood, etc.

The difference in pitch between two notes is called an interval. The most basic interval is the unison, which is simply two notes of the same pitch. The octave interval is two pitches that are either double or half the frequency of one another. The unique characteristics of octaves gave rise to the concept of pitch class: pitches of the same letter name that occur in different octaves may be grouped into a single "class" by ignoring the difference in octave. For example, a high C and a low C are members of the same pitch class—the class that contains all C's. [29]

Musical tuning systems, or temperaments, determine the precise size of intervals. Tuning systems vary widely within and between world cultures. In Western culture, there have long been several competing tuning systems, all with different qualities. Internationally, the system known as equal temperament is most commonly used today because it is considered the most satisfactory compromise that allows instruments of fixed tuning (e.g. the piano) to sound acceptably in tune in all keys.

Scales and modes[edit]

Notes can be arranged in a variety of scales and modes. Western music theory generally divides the octave into a series of twelve pitches, called a chromatic scale, within which the interval between adjacent tones is called a half step, or semitone. Selecting tones from this set of 12 and arranging them in patterns of semitones and whole tones creates other scales.[30]

The most commonly encountered scales are the seven-toned major, the harmonic minor, the melodic minor, and the natural minor. Other examples of scales are the octatonic scale and the pentatonic or five-tone scale, which is common in folk music and blues. Non-Western cultures often use scales that do not correspond with an equally divided twelve-tone division of the octave. For example, classical Ottoman, Persian, Indian and Arabic musical systems often make use of multiples of quarter tones (half the size of a semitone, as the name indicates), for instance in 'neutral' seconds (three quarter tones) or 'neutral' thirds (seven quarter tones)—they do not normally use the quarter tone itself as a direct interval.[30]

In traditional Western notation, the scale used for a composition is usually indicated by a key signature at the beginning to designate the pitches that make up that scale. As the music progresses, the pitches used may change and introduce a different scale. Music can be transposed from one scale to another for various purposes, often to accommodate the range of a vocalist. Such transposition raises or lowers the overall pitch range, but preserves the intervallic relationships of the original scale. For example, transposition from the key of C major to D major raises all pitches of the scale of C major equally by a whole tone. Since the interval relationships remain unchanged, transposition may be unnoticed by a listener, however other qualities may change noticeably because transposition changes the relationship of the overall pitch range compared to the range of the instruments or voices that perform the music. This often affects the music's overall sound, as well as having technical implications for the performers.[31]

The interrelationship of the keys most commonly used in Western tonal music is conveniently shown by the circle of fifths. Unique key signatures are also sometimes devised for a particular composition. During the Baroque period, emotional associations with specific keys, known as the doctrine of the affections, were an important topic in music theory, but the unique tonal colorings of keys that gave rise to that doctrine were largely erased with the adoption of equal temperament. However, many musicians continue to feel that certain keys are more appropriate to certain emotions than others. Indian classical music theory continues to strongly associate keys with emotional states, times of day, and other extra-musical concepts and notably, does not employ equal temperament.

Consonance and dissonance[edit]

Consonance and dissonance are subjective qualities of the sonority of intervals that vary widely in different cultures and over the ages. Consonance (or concord) is the quality of an interval or chord that seems stable and complete in itself. Dissonance (or discord) is the opposite in that it feels incomplete and "wants to" resolve to a consonant interval. Dissonant intervals seem to clash. Consonant intervals seem to sound comfortable together. Commonly, perfect fourths, fifths, and octaves and all major and minor thirds and sixths are considered consonant. All others are dissonant to a greater or lesser degree.[32]

Context and many other aspects can affect apparent dissonance and consonance. For example, in a Debussy prelude, a major second may sound stable and consonant, while the same interval may sound dissonant in a Bach fugue. In the Common practice era, the perfect fourth is considered dissonant when not supported by a lower third or fifth. Since the early 20th century, Arnold Schoenberg's concept of "emancipated" dissonance, in which traditionally dissonant intervals can be treated as "higher," more remote consonances, has become more widely accepted.[32]

Rhythm[edit]

Rhythm is produced by the sequential arrangement of sounds and silences in time. Meter measures music in regular pulse groupings, called measures or bars. The time signature or meter signature specifies how many beats are in a measure, and which value of written note is counted or felt as a single beat.

Through increased stress, or variations in duration or articulation, particular tones may be accented. There are conventions in most musical traditions for regular and hierarchical accentuation of beats to reinforce a given meter. Syncopated rhythms contradict those conventions by accenting unexpected parts of the beat.[33] Playing simultaneous rhythms in more than one time signature is called polyrhythm.[34]

In recent years, rhythm and meter have become an important area of research among music scholars. The most highly cited of these recent scholars are Maury Yeston,[35] Fred Lerdahl and Ray Jackendoff,[36] Jonathan Kramer,[37] and Justin London.[38]

Melody[edit]

A melody is a series of tones perceived as an entity,[citation needed] sounding in succession that typically move toward a climax of tension then resolve to a state of rest. Because melody is such a prominent aspect in so much music, its construction and other qualities are a primary interest of music theory.

The basic elements of melody are pitch, duration, rhythm, and tempo. The tones of a melody are usually drawn from pitch systems such as scales or modes. Melody may consist, to increasing degree, of the figure, motive, semi-phrase, antecedent and consequent phrase, and period or sentence. The period may be considered the complete melody, however some examples combine two periods, or use other combinations of constituents to create larger form melodies.[40]

Chord[edit]

A chord, in music, is any harmonic set of three or more notes that is heard as if sounding simultaneously.[41]: pp. 67, 359 [42]: p. 63 These need not actually be played together: arpeggios and broken chords may, for many practical and theoretical purposes, constitute chords. Chords and sequences of chords are frequently used in modern Western, West African,[43] and Oceanian[44] music, whereas they are absent from the music of many other parts of the world.[45]: p. 15

The most frequently encountered chords are triads, so called because they consist of three distinct notes: further notes may be added to give seventh chords, extended chords, or added tone chords. The most common chords are the major and minor triads and then the augmented and diminished triads. The descriptions major, minor, augmented, and diminished are sometimes referred to collectively as chordal quality. Chords are also commonly classed by their root note—so, for instance, the chord C major may be described as a triad of major quality built on the note C. Chords may also be classified by inversion, the order in which the notes are stacked.

A series of chords is called a chord progression. Although any chord may in principle be followed by any other chord, certain patterns of chords have been accepted as establishing key in common-practice harmony. To describe this, chords are numbered, using Roman numerals (upward from the key-note),[46] per their diatonic function. Common ways of notating or representing chords[47] in western music other than conventional staff notation include Roman numerals, figured bass (much used in the Baroque era), chord letters (sometimes used in modern musicology), and various systems of chord charts typically found in the lead sheets used in popular music to lay out the sequence of chords so that the musician may play accompaniment chords or improvise a solo.

Harmony[edit]

In music, harmony is the use of simultaneous pitches (tones, notes), or chords.[45]: p. 15 The study of harmony involves chords and their construction and chord progressions and the principles of connection that govern them.[48] Harmony is often said to refer to the "vertical" aspect of music, as distinguished from melodic line, or the "horizontal" aspect.[49] Counterpoint, which refers to the interweaving of melodic lines, and polyphony, which refers to the relationship of separate independent voices, is thus sometimes distinguished from harmony.[50]

In popular and jazz harmony, chords are named by their root plus various terms and characters indicating their qualities. For example, a lead sheet may indicate chords such as C major, D minor, and G dominant seventh. In many types of music, notably Baroque, Romantic, modern, and jazz, chords are often augmented with "tensions". A tension is an additional chord member that creates a relatively dissonant interval in relation to the bass. It is part of a chord, but is not one of the chord tones (1 3 5 7). Typically, in the classical common practice period a dissonant chord (chord with tension) "resolves" to a consonant chord. Harmonization usually sounds pleasant to the ear when there is a balance between the consonant and dissonant sounds. In simple words, that occurs when there is a balance between "tense" and "relaxed" moments.[51][unreliable source?]

Timbre[edit]

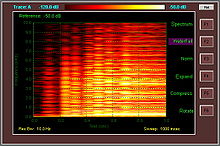

Timbre, sometimes called "color", or "tone color," is the principal phenomenon that allows us to distinguish one instrument from another when both play at the same pitch and volume, a quality of a voice or instrument often described in terms like bright, dull, shrill, etc. It is of considerable interest in music theory, especially because it is one component of music that has as yet, no standardized nomenclature. It has been called "... the psychoacoustician's multidimensional waste-basket category for everything that cannot be labeled pitch or loudness,"[52] but can be accurately described and analyzed by Fourier analysis and other methods[53] because it results from the combination of all sound frequencies, attack and release envelopes, and other qualities that a tone comprises.

Timbre is principally determined by two things: (1) the relative balance of overtones produced by a given instrument due its construction (e.g. shape, material), and (2) the envelope of the sound (including changes in the overtone structure over time). Timbre varies widely between different instruments, voices, and to lesser degree, between instruments of the same type due to variations in their construction, and significantly, the performer's technique. The timbre of most instruments can be changed by employing different techniques while playing. For example, the timbre of a trumpet changes when a mute is inserted into the bell, the player changes their embouchure, or volume.[citation needed]

A voice can change its timbre by the way the performer manipulates their vocal apparatus, (e.g. the shape of the vocal cavity or mouth). Musical notation frequently specifies alteration in timbre by changes in sounding technique, volume, accent, and other means. These are indicated variously by symbolic and verbal instruction. For example, the word dolce (sweetly) indicates a non-specific, but commonly understood soft and "sweet" timbre. Sul tasto instructs a string player to bow near or over the fingerboard to produce a less brilliant sound. Cuivre instructs a brass player to produce a forced and stridently brassy sound. Accent symbols like marcato (^) and dynamic indications (pp) can also indicate changes in timbre.[54]

Dynamics[edit]

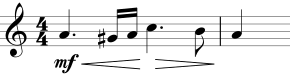

In music, "dynamics" normally refers to variations of intensity or volume, as may be measured by physicists and audio engineers in decibels or phons. In music notation, however, dynamics are not treated as absolute values, but as relative ones. Because they are usually measured subjectively, there are factors besides amplitude that affect the performance or perception of intensity, such as timbre, vibrato, and articulation.

The conventional indications of dynamics are abbreviations for Italian words like forte (f) for loud and piano (p) for soft. These two basic notations are modified by indications including mezzo piano (mp) for moderately soft (literally "half soft") and mezzo forte (mf) for moderately loud, sforzando or sforzato (sfz) for a surging or "pushed" attack, or fortepiano (fp) for a loud attack with a sudden decrease to a soft level. The full span of these markings usually range from a nearly inaudible pianissississimo (pppp) to a loud-as-possible fortissississimo (ffff).

Greater extremes of pppppp and fffff and nuances such as p+ or più piano are sometimes found. Other systems of indicating volume are also used in both notation and analysis: dB (decibels), numerical scales, colored or different sized notes, words in languages other than Italian, and symbols such as those for progressively increasing volume (crescendo) or decreasing volume (diminuendo or decrescendo), often called "hairpins" when indicated with diverging or converging lines as shown in the graphic above.

Articulation[edit]

Articulation is the way the performer sounds notes. For example, staccato is the shortening of duration compared to the written note value, legato performs the notes in a smoothly joined sequence with no separation. Articulation is often described rather than quantified, therefore there is room to interpret how to execute precisely each articulation.

For example, staccato is often referred to as "separated" or "detached" rather than having a defined or numbered amount by which to reduce the notated duration. Violin players use a variety of techniques to perform different qualities of staccato. The manner in which a performer decides to execute a given articulation is usually based on the context of the piece or phrase, but many articulation symbols and verbal instructions depend on the instrument and musical period (e.g. viol, wind; classical, baroque; etc.).

There is a set of articulations that most instruments and voices perform in common. They are—from long to short: legato (smooth, connected); tenuto (pressed or played to full notated duration); marcato (accented and detached); staccato ("separated", "detached"); martelé (heavily accented or "hammered").[contradictory] Many of these can be combined to create certain "in-between" articulations. For example, portato is the combination of tenuto and staccato. Some instruments have unique methods by which to produce sounds, such as spicatto for bowed strings, where the bow bounces off the string.

Texture[edit]

In music, texture is how the melodic, rhythmic, and harmonic materials are combined in a composition, thus determining the overall quality of the sound in a piece. Texture is often described in regard to the density, or thickness, and range, or width, between lowest and highest pitches, in relative terms as well as more specifically distinguished according to the number of voices, or parts, and the relationship between these voices. For example, a thick texture contains many "layers" of instruments. One of these layers could be a string section, or another brass.

The thickness also is affected by the number and the richness of the instruments playing the piece. The thickness varies from light to thick. A lightly textured piece will have light, sparse scoring. A thickly or heavily textured piece will be scored for many instruments. A piece's texture may be affected by the number and character of parts playing at once, the timbre of the instruments or voices playing these parts and the harmony, tempo, and rhythms used.[56] The types categorized by number and relationship of parts are analyzed and determined through the labeling of primary textural elements: primary melody, secondary melody, parallel supporting melody, static support, harmonic support, rhythmic support, and harmonic and rhythmic support.[57][incomplete short citation]

Common types included monophonic texture (a single melodic voice, such as a piece for solo soprano or solo flute), biphonic texture (two melodic voices, such as a duo for bassoon and flute in which the bassoon plays a drone note and the flute plays the melody), polyphonic texture and homophonic texture (chords accompanying a melody).[citation needed]

Form or structure[edit]

The term musical form (or musical architecture) refers to the overall structure or plan of a piece of music, and it describes the layout of a composition as divided into sections.[59] In the tenth edition of The Oxford Companion to Music, Percy Scholes defines musical form as "a series of strategies designed to find a successful mean between the opposite extremes of unrelieved repetition and unrelieved alteration."[60] According to Richard Middleton, musical form is "the shape or structure of the work." He describes it through difference: the distance moved from a repeat; the latter being the smallest difference. Difference is quantitative and qualitative: how far, and of what type, different. In many cases, form depends on statement and restatement, unity and variety, and contrast and connection.[61]

Expression[edit]

Musical expression is the art of playing or singing music with emotional communication. The elements of music that comprise expression include dynamic indications, such as forte or piano, phrasing, differing qualities of timbre and articulation, color, intensity, energy and excitement. All of these devices can be incorporated by the performer. A performer aims to elicit responses of sympathetic feeling in the audience, and to excite, calm or otherwise sway the audience's physical and emotional responses. Musical expression is sometimes thought to be produced by a combination of other parameters, and sometimes described as a transcendent quality that is more than the sum of measurable quantities such as pitch or duration.

Expression on instruments can be closely related to the role of the breath in singing, and the voice's natural ability to express feelings, sentiment and deep emotions.[clarification needed] Whether these can somehow be categorized is perhaps the realm of academics, who view expression as an element of musical performance that embodies a consistently recognizable emotion, ideally causing a sympathetic emotional response in its listeners.[62] The emotional content of musical expression is distinct from the emotional content of specific sounds (e.g., a startlingly-loud 'bang') and of learned associations (e.g., a national anthem), but can rarely be completely separated from its context.[citation needed]

The components of musical expression continue to be the subject of extensive and unresolved dispute.[63][64][65][66][67][68]

Notation[edit]

Musical notation is the written or symbolized representation of music. This is most often achieved by the use of commonly understood graphic symbols and written verbal instructions and their abbreviations. There are many systems of music notation from different cultures and different ages. Traditional Western notation evolved during the Middle Ages and remains an area of experimentation and innovation.[69]In the 2000s, computer file formats have become important as well.[70] Spoken language and hand signs are also used to symbolically represent music, primarily in teaching.

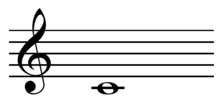

In standard Western music notation, tones are represented graphically by symbols (notes) placed on a staff or staves, the vertical axis corresponding to pitch and the horizontal axis corresponding to time. Note head shapes, stems, flags, ties and dots are used to indicate duration. Additional symbols indicate keys, dynamics, accents, rests, etc. Verbal instructions from the conductor are often used to indicate tempo, technique, and other aspects.

In Western music, a range of different music notation systems are used. In Western Classical music, conductors use printed scores that show all of the instruments' parts and orchestra members read parts with their musical lines written out. In popular styles of music, much less of the music may be notated. A rock band may go into a recording session with just a handwritten chord chart indicating the song's chord progression using chord names (e.g., C major, D minor, G7, etc.). All of the chord voicings, rhythms and accompaniment figures are improvised by the band members.

As academic discipline[edit]

The scholarly study of music theory in the twentieth century has a number of different subfields, each of which takes a different perspective on what are the primary phenomenon of interest and the most useful methods for investigation.

Analysis[edit]

Musical analysis is the attempt to answer the question how does this music work? The method employed to answer this question, and indeed exactly what is meant by the question, differs from analyst to analyst, and according to the purpose of the analysis. According to Ian Bent, "analysis, as a pursuit in its own right, came to be established only in the late 19th century; its emergence as an approach and method can be traced back to the 1750s. However, it existed as a scholarly tool, albeit an auxiliary one, from the Middle Ages onwards."[71][incomplete short citation] Adolf Bernhard Marx was influential in formalising concepts about composition and music understanding towards the second half of the 19th century. The principle of analysis has been variously criticized, especially by composers, such as Edgard Varèse's claim that, "to explain by means of [analysis] is to decompose, to mutilate the spirit of a work".[72]

Schenkerian analysis is a method of musical analysis of tonal music based on the theories of Heinrich Schenker (1868–1935). The goal of a Schenkerian analysis is to interpret the underlying structure of a tonal work and to help reading the score according to that structure. The theory's basic tenets can be viewed as a way of defining tonality in music. A Schenkerian analysis of a passage of music shows hierarchical relationships among its pitches, and draws conclusions about the structure of the passage from this hierarchy. The analysis makes use of a specialized symbolic form of musical notation that Schenker devised to demonstrate various techniques of elaboration. The most fundamental concept of Schenker's theory of tonality may be that of tonal space.[73] The intervals between the notes of the tonic triad form a tonal space that is filled with passing and neighbour notes, producing new triads and new tonal spaces, open for further elaborations until the surface of the work (the score) is reached.

Although Schenker himself usually presents his analyses in the generative direction, starting from the fundamental structure (Ursatz) to reach the score, the practice of Schenkerian analysis more often is reductive, starting from the score and showing how it can be reduced to its fundamental structure. The graph of the Ursatz is arrhythmic, as is a strict-counterpoint cantus firmus exercise.[74] Even at intermediate levels of the reduction, rhythmic notation (open and closed noteheads, beams and flags) shows not rhythm but the hierarchical relationships between the pitch-events. Schenkerian analysis is subjective. There is no mechanical procedure involved and the analysis reflects the musical intuitions of the analyst.[75] The analysis represents a way of hearing (and reading) a piece of music.

Transformational theory is a branch of music theory developed by David Lewin in the 1980s, and formally introduced in his 1987 work, Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations. The theory, which models musical transformations as elements of a mathematical group, can be used to analyze both tonal and atonal music. The goal of transformational theory is to change the focus from musical objects—such as the "C major chord" or "G major chord"—to relations between objects. Thus, instead of saying that a C major chord is followed by G major, a transformational theorist might say that the first chord has been "transformed" into the second by the "Dominant operation." (Symbolically, one might write "Dominant(C major) = G major.") While traditional musical set theory focuses on the makeup of musical objects, transformational theory focuses on the intervals or types of musical motion that can occur. According to Lewin's description of this change in emphasis, "[The transformational] attitude does not ask for some observed measure of extension between reified 'points'; rather it asks: 'If I am at s and wish to get to t, what characteristic gesture should I perform in order to arrive there?'"[76]

Music perception and cognition[edit]

Music psychology or the psychology of music may be regarded as a branch of both psychology and musicology. It aims to explain and understand musical behavior and experience, including the processes through which music is perceived, created, responded to, and incorporated into everyday life.[77][78] Modern music psychology is primarily empirical; its knowledge tends to advance on the basis of interpretations of data collected by systematic observation of and interaction with human participants. Music psychology is a field of research with practical relevance for many areas, including music performance, composition, education, criticism, and therapy, as well as investigations of human aptitude, skill, intelligence, creativity, and social behavior.

Music psychology can shed light on non-psychological aspects of musicology and musical practice. For example, it contributes to music theory through investigations of the perception and computational modelling of musical structures such as melody, harmony, tonality, rhythm, meter, and form. Research in music history can benefit from systematic study of the history of musical syntax, or from psychological analyses of composers and compositions in relation to perceptual, affective, and social responses to their music. Ethnomusicology can benefit from psychological approaches to the study of music cognition in different cultures.[79][citation needed]

Genre and technique[edit]

A music genre is a conventional category that identifies some pieces of music as belonging to a shared tradition or set of conventions.[80] It is to be distinguished from musical form and musical style, although in practice these terms are sometimes used interchangeably.[81][failed verification]

Music can be divided into different genres in many different ways. The artistic nature of music means that these classifications are often subjective and controversial, and some genres may overlap. There are even varying academic definitions of the term genre itself. In his book Form in Tonal Music, Douglass M. Green distinguishes between genre and form. He lists madrigal, motet, canzona, ricercar, and dance as examples of genres from the Renaissance period. To further clarify the meaning of genre, Green writes, "Beethoven's Op. 61 and Mendelssohn's Op. 64 are identical in genre—both are violin concertos—but different in form. However, Mozart's Rondo for Piano, K. 511, and the Agnus Dei from his Mass, K. 317 are quite different in genre but happen to be similar in form."[82] Some, like Peter van der Merwe, treat the terms genre and style as the same, saying that genre should be defined as pieces of music that came from the same style or "basic musical language."[83]

Others, such as Allan F. Moore, state that genre and style are two separate terms, and that secondary characteristics such as subject matter can also differentiate between genres.[84] A music genre or subgenre may also be defined by the musical techniques, the style, the cultural context, and the content and spirit of the themes. Geographical origin is sometimes used to identify a music genre, though a single geographical category will often include a wide variety of subgenres. Timothy Laurie argues that "since the early 1980s, genre has graduated from being a subset of popular music studies to being an almost ubiquitous framework for constituting and evaluating musical research objects".[85]

Musical technique is the ability of instrumental and vocal musicians to exert optimal control of their instruments or vocal cords to produce precise musical effects. Improving technique generally entails practicing exercises that improve muscular sensitivity and agility. To improve technique, musicians often practice fundamental patterns of notes such as the natural, minor, major, and chromatic scales, minor and major triads, dominant and diminished sevenths, formula patterns and arpeggios. For example, triads and sevenths teach how to play chords with accuracy and speed. Scales teach how to move quickly and gracefully from one note to another (usually by step). Arpeggios teach how to play broken chords over larger intervals. Many of these components of music are found in compositions, for example, a scale is a very common element of classical and romantic era compositions.[citation needed]

Heinrich Schenker argued that musical technique's "most striking and distinctive characteristic" is repetition.[86] Works known as études (meaning "study") are also frequently used for the improvement of technique.

Mathematics[edit]

Music theorists sometimes use mathematics to understand music, and although music has no axiomatic foundation in modern mathematics, mathematics is "the basis of sound" and sound itself "in its musical aspects... exhibits a remarkable array of number properties", simply because nature itself "is amazingly mathematical".[87] The attempt to structure and communicate new ways of composing and hearing music has led to musical applications of set theory, abstract algebra and number theory. Some composers have incorporated the golden ratio and Fibonacci numbers into their work.[88][89] There is a long history of examining the relationships between music and mathematics. Though ancient Chinese, Egyptians and Mesopotamians are known to have studied the mathematical principles of sound,[90] the Pythagoreans (in particular Philolaus and Archytas)[91] of ancient Greece were the first researchers known to have investigated the expression of musical scales in terms of numerical ratios.

In the modern era, musical set theory uses the language of mathematical set theory in an elementary way to organize musical objects and describe their relationships. To analyze the structure of a piece of (typically atonal) music using musical set theory, one usually starts with a set of tones, which could form motives or chords. By applying simple operations such as transposition and inversion, one can discover deep structures in the music. Operations such as transposition and inversion are called isometries because they preserve the intervals between tones in a set. Expanding on the methods of musical set theory, some theorists have used abstract algebra to analyze music. For example, the pitch classes in an equally tempered octave form an abelian group with 12 elements. It is possible to describe just intonation in terms of a free abelian group.[92]

Serial composition and set theory[edit]

In music theory, serialism is a method or technique of composition that uses a series of values to manipulate different musical elements. Serialism began primarily with Arnold Schoenberg's twelve-tone technique, though his contemporaries were also working to establish serialism as one example of post-tonal thinking. Twelve-tone technique orders the twelve notes of the chromatic scale, forming a row or series and providing a unifying basis for a composition's melody, harmony, structural progressions, and variations. Other types of serialism also work with sets, collections of objects, but not necessarily with fixed-order series, and extend the technique to other musical dimensions (often called "parameters"), such as duration, dynamics, and timbre. The idea of serialism is also applied in various ways in the visual arts, design, and architecture[93]

"Integral serialism" or "total serialism" is the use of series for aspects such as duration, dynamics, and register as well as pitch. [94] Other terms, used especially in Europe to distinguish post-World War II serial music from twelve-tone music and its American extensions, are "general serialism" and "multiple serialism".[95]

Musical set theory provides concepts for categorizing musical objects and describing their relationships. Many of the notions were first elaborated by Howard Hanson (1960) in connection with tonal music, and then mostly developed in connection with atonal music by theorists such as Allen Forte (1973), drawing on the work in twelve-tone theory of Milton Babbitt. The concepts of set theory are very general and can be applied to tonal and atonal styles in any equally tempered tuning system, and to some extent more generally than that.[citation needed]

One branch of musical set theory deals with collections (sets and permutations) of pitches and pitch classes (pitch-class set theory), which may be ordered or unordered, and can be related by musical operations such as transposition, inversion, and complementation. The methods of musical set theory are sometimes applied to the analysis of rhythm as well.[citation needed]

Musical semiotics[edit]

Music semiology (semiotics) is the study of signs as they pertain to music on a variety of levels. Following Roman Jakobson, Kofi Agawu adopts the idea of musical semiosis being introversive or extroversive—that is, musical signs within a text and without.[citation needed] "Topics," or various musical conventions (such as horn calls, dance forms, and styles), have been treated suggestively by Agawu, among others.[citation needed] The notion of gesture is beginning to play a large role in musico-semiotic enquiry.[citation needed]

- "There are strong arguments that music inhabits a semiological realm which, on both ontogenetic and phylogenetic levels, has developmental priority over verbal language."[96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][incomplete short citation][clarification needed]

Writers on music semiology include Kofi Agawu (on topical theory,[citation needed] Heinrich Schenker,[104][105] Robert Hatten (on topic, gesture)[citation needed], Raymond Monelle (on topic, musical meaning)[citation needed], Jean-Jacques Nattiez (on introversive taxonomic analysis and ethnomusicological applications)[citation needed], Anthony Newcomb (on narrativity)[citation needed], and Eero Tarasti[citation needed] (generally considered the founder of musical semiotics).[clarification needed]

Roland Barthes, himself a semiotician and skilled amateur pianist, wrote about music in Image-Music-Text,[full citation needed] The Responsibilities of Form,[full citation needed] and Eiffel Tower,[full citation needed] though he did not consider music to be a semiotic system[citation needed].

Signs, meanings in music, happen essentially through the connotations of sounds, and through the social construction, appropriation and amplification of certain meanings associated with these connotations. The work of Philip Tagg (Ten Little Tunes,[full citation needed] Fernando the Flute,[full citation needed] Music's Meanings[full citation needed]) provides one of the most complete and systematic analysis of the relation between musical structures and connotations in western and especially popular, television and film music. The work of Leonard B. Meyer in Style and Music[full citation needed] theorizes the relationship between ideologies and musical structures and the phenomena of style change, and focuses on romanticism as a case study.

Education and careers[edit]

Music theory in the practical sense has been a part of education at conservatories and music schools for centuries, but the status music theory currently has within academic institutions is relatively recent. In the 1970s, few universities had dedicated music theory programs, many music theorists had been trained as composers or historians, and there was a belief among theorists that the teaching of music theory was inadequate and that the subject was not properly recognised as a scholarly discipline in its own right.[106] A growing number of scholars began promoting the idea that music theory should be taught by theorists, rather than composers, performers or music historians.[106] This led to the founding of the Society for Music Theory in the United States in 1977. In Europe, the French Société d'Analyse musicale was founded in 1985. It called the First European Conference of Music Analysis for 1989, which resulted in the foundation of the Société belge d'Analyse musicale in Belgium and the Gruppo analisi e teoria musicale in Italy the same year, the Society for Music Analysis in the UK in 1991, the Vereniging voor Muziektheorie in the Netherlands in 1999 and the Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie in Germany in 2000.[107] They were later followed by the Russian Society for Music Theory in 2013, the Polish Society for Music Analysis in 2015 and the Sociedad de Análisis y Teoría Musical in Spain in 2020, and others are in construction. These societies coordinate the publication of music theory scholarship and support the professional development of music theory researchers.

As part of their initial training, music theorists will typically complete a B.Mus or a B.A. in music (or a related field) and in many cases an M.A. in music theory. Some individuals apply directly from a bachelor's degree to a PhD, and in these cases, they may not receive an M.A. In the 2010s, given the increasingly interdisciplinary nature of university graduate programs, some applicants for music theory PhD programs may have academic training both in music and outside of music (e.g., a student may apply with a B.Mus and a Masters in Music Composition or Philosophy of Music).

Most music theorists work as instructors, lecturers or professors in colleges, universities or conservatories. The job market for tenure-track professor positions is very competitive: with an average of around 25 tenure-track positions advertised per year in the past decade, 80–100 PhD graduates are produced each year (according to the Survey of Earned Doctorates) who compete not only with each other for those positions but with job seekers that received PhD's in previous years who are still searching for a tenure-track job. Applicants must hold a completed PhD or the equivalent degree (or expect to receive one within a year of being hired—called an "ABD", for "All But Dissertation" stage) and (for more senior positions) have a strong record of publishing in peer-reviewed journals. Some PhD-holding music theorists are only able to find insecure positions as sessional lecturers. The job tasks of a music theorist are the same as those of a professor in any other humanities discipline: teaching undergraduate and/or graduate classes in this area of specialization and, in many cases some general courses (such as Music appreciation or Introduction to Music Theory), conducting research in this area of expertise, publishing research articles in peer-reviewed journals, authoring book chapters, books or textbooks, traveling to conferences to present papers and learn about research in the field, and, if the program includes a graduate school, supervising M.A. and PhD students and giving them guidance on the preparation of their theses and dissertations. Some music theory professors may take on senior administrative positions in their institution, such as Dean or Chair of the School of Music.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ See Boethius's De institutione musica,[2] in which he disdains "musica instrumentalis" as beneath the "true" musician who studies music in the abstract: Multo enim est maius atque auctius scire, quod quisque faciat, quam ipsum illud efficere, quod sciat ("It is much better to know what one does than to do what one knows").

- ^ See, for example, chapters 4–7 of Christensen, Thomas (2002). The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- ^ See the List of music theorists#7th–14th centuries, which includes several Arabic theorists; see also d'Erlanger 1930–56, 1:xv-xxiv.

References[edit]

- ^ Fallows, David (2011). Theory. The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford Music Online. ISBN 978-0199579037. Retrieved 11 September 2016.

- ^ a b Boethius 1989.

- ^ OED.

- ^ Palisca and Bent n.d., Theory, theorists. 1. Definitions.

- ^ Mirelman 2010; Mirelman 2013; Wulstan 1968; Kümmel 1970; Kilmer 1971; Kilmer and Mirelman n.d.

- ^ Mirelman 2013, 43–44.

- ^ a b c Lam

- ^ Service 2013.

- ^ The Nāțyaśāstra, A Treatise on Hindu Dramaturgy and Histrionics, attributed to Bharata Muni, translated from the Sanskrit with introduction and notes by Manomohan Ghosh, vol. II, Calcutta, The Asiatic Society, 1961. See particularly pp. 5–19 of the Introduction, The Ancient Indian Theory and Practice of Music.

- ^ Thomas J. Mathiesen, "Greek Music Theory", The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, Th. Christensen ed., Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 2002, pp. 112–13.

- ^ English translation in Andrew Barker, Greek Musical Writings, vol. 2: Harmonic and Acoustic Theory, Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1989, pp. 191–208.

- ^ Manik 1969, 24–33.

- ^ Wright 2001a; Wright 2001b; Manik 1969, 22–24.

- ^ Rodolphe d'Erlanger, La Musique arabe, vol. I, pp. 1–306; vol. II, pp. 1–101.

- ^ d'Erlanger 1930–56, 2:103–245.

- ^ Shiloah 1964.

- ^ d'Erlanger 1930–56, 3:1–182.

- ^ Anon. LXII in Amnon Shiloah, The Theory of Music in Arabic Writings (c. 900–1900): Descriptive Catalogue of Manuscripts in Libraries of Europe and the U.S.A., RISM, München, G. Henle Verlag, 1979. See d'Erlanger 1930–56, 3:183–566

- ^ Ghrab 2009.

- ^ a b c Shiloah, Amnon (2003). The Theory of Music in Arabic Writings (c. 900–1900). Germany: G. Henle Verlag Munchen. pp. 48, 58, 60–61. ISBN 978-0-8203-0426-7.

- ^ a b Palisca and Bent n.d., §5 Early Middle Ages.

- ^ Palisca and Bent n.d., Theory, theorists §5 Early Middle Ages: "Boethius could provide a model only for that part of theory which underlies but does not give rules for composition or performance. The first surviving strictly musical treatise of Carolingian times is directed towards musical practice, the Musica disciplina of Aurelian of Réôme (9th century)."

- ^ "Guy Aretini's letter to the unknown : modern translation of the letter". Hs-augsburg.de. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Kubik 2010, passim.

- ^ Ekwueme 1974, passim.

- ^ Cobb, Buell E. Jr. (1978). The Sacred Harp: A Tradition and Its Music. United States of America: The University of Georgia Press Athens. pp. 4–5, 60–61. ISBN 978-0-8203-0426-7.

- ^ Palisca and Bent n.d.

- ^ Hartmann 2005,[page needed].

- ^ Bartlette and Laitz 2010,[page needed].

- ^ a b Touma 1996,[page needed].

- ^ Forsyth 1935, 73–74.

- ^ a b Latham 2002,[page needed].

- ^ Syncopation. Oxford Dictionary of Music. Oxford University Press. 2013. ISBN 978-0199578108. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

Syncopation is achieved by accenting a weak instead of a strong beat, by putting rests on strong beats, by holding on over strong beats, and by introducing a sudden change of time‐signature.

- ^ "Polyrhythm". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 11 August 2017.

The superposition of different rhythms or metres.

- ^ Yeston 1976.

- ^ Lerdahl and Jackendoff 1985.

- ^ Kramer 1988.

- ^ London 2004.

- ^ Kliewer 1975,[page needed].

- ^ Stein 1979, 3–47.

- ^ Benward and Saker 2003.

- ^ Károlyi 1965.

- ^ Mitchell 2008.

- ^ Linkels n.d.,[page needed].

- ^ a b Malm 1996.

- ^ Schoenberg 1983, 1–2.

- ^ Benward and Saker 2003, 77.

- ^ Dahlhaus 2009.

- ^ Jamini 2005, 147.

- ^ Faculty of Arts & Sciences. "Pitch Structure: Harmony and Counterpoint". Theory of Music – Pitch Structure: The Chromatic Scale. Harvard University. Retrieved 2 October 2020.

- ^ "Chapter 2 ELEMENTS AND CONCEPTS OF MUSIC (With reference to Hindustani and Jazz music)" (PDF). Shodhganga.inflibnet.ac.in. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ McAdams and Bregman 1979, 34.

- ^ Mannell n.d.

- ^ "How Loud? How Soft?" (PDF). Sheffield-Sheffield Lake City Schools.

- ^ Benward and Saker 2003, p. 133.

- ^ Benward and Saker 2003,[page needed].

- ^ Isaac and Russell 2003, 136.

- ^ "Canon | music". Britannica.com. Retrieved 17 December 2017.

- ^ Brandt 2007.

- ^ Scholes 1977.

- ^ Middleton 1999,[page needed].

- ^ London n.d.

- ^ Avison 1752,[page needed].

- ^ Christiani 1885,[page needed].

- ^ Lussy 1892,[page needed].

- ^ Darwin 1913,[page needed].

- ^ Sorantin 1932,[page needed].

- ^ Davies 1994,[page needed].

- ^ Read 1969,[page needed]; Stone 1980,[page needed].

- ^ Castan 2009.

- ^ Bent 1987, 6.

- ^ Quoted in Bernard 1981, 1

- ^ Schenker described the concept in a paper titled Erläuterungen ("Elucidations"), which he published four times between 1924 and 1926: Der Tonwille (Vienna, Tonwille Verlag, 1924) vol. 8–9, pp. 49–51, vol. 10, pp. 40–42; Das Meisterwerk in der Musik (München, Drei Masken Verlag), vol. 1 (1925), pp. 201–05; 2 (1926), pp. 193–97. English translation, Der Tonwille, Oxford University Press, vol. 2, pp. 117–18 (the translation, although made from vols. 8–9 of the German original, gives as original pagination that of Das Meisterwerk 1; the text is the same). The concept of tonal space is still present in Schenker (1979, especially p. 14, § 13), but less clearly than in the earlier presentation.

- ^ Schenker 1979, p. 15, § 21.

- ^ Snarrenberg 1997,[page needed].

- ^ Lewin 1987, 159.

- ^ Tan, Peter, and Rom 2010, 2.

- ^ Thompson n.d., 320.

- ^ Martin, Clayton; Clayton, Martin (2008). Time in Indian Music: Rhythm, Metre, and Form in North Indian Rag Performance. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195339680.

- ^ Samson n.d.

- ^ Wong 2011.

- ^ Green 1979, 1.

- ^ van der Merwe 1989, 3.

- ^ Moore 2001, 432–33.

- ^ Laurie 2014, 284.

- ^ Kivy 1993, 327.

- ^ Smith Brindle 1987, 42–43.

- ^ Smith Brindle 1987, chapter 6, passim.

- ^ Garland and Kahn 1995,[page needed].

- ^ Smith Brindle 1987, 42.

- ^ Purwins 2005, 22–24.

- ^ Wohl 2005.

- ^ Bandur 2001, 5, 12, 74; Gerstner 1964, passim

- ^ Whittall 2008, 273.

- ^ Grant 2001, 5–6.

- ^ Middleton 1990, 172.

- ^ Nattiez 1976.

- ^ Nattiez 1990.

- ^ Nattiez1989.

- ^ Stefani 1973.

- ^ Stefani 1976.

- ^ Baroni 1983.

- ^ Semiotica 1987, 66:1–3.

- ^ Dunsby & Stopford 1981, 49–53.

- ^ Meeùs 2017, 81–96.

- ^ a b McCreless n.d.

- ^ Meeùs 2015, 111.

Sources[edit]

- Avison, Charles (1752). An Essay on Musical Expression. London: C. Davis.

- Bandur, Markus. 2001. Aesthetics of Total Serialism: Contemporary Research from Music to Architecture. Basel, Boston and Berlin: Birkhäuser.

- Baroni, Mario (1983). "The Concept of Musical Grammar", translated by Simon Maguire and William Drabkin. Music Analysis 2, no. 2:175–208.

- Bartlette, Christopher, and Steven G. Laitz (2010). Graduate Review of Tonal Theory. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-537698-2.

- Bent, Ian (1987). Analysis, The New Grove Handbooks in Music ISBN 0-333-41732-1.

- Benward, Bruce, and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2003). Music: In Theory and Practice, seventh edition, 2 volumes. Boston: McGraw-Hill ISBN 978-0-07-294262-0.

- Bernard, Jonathan (1981). "Pitch/Register in the Music of Edgar Varèse." Music Theory Spectrum 3: 1–25.

- Boethius, Anicius Manlius Severinus (1989). Claude V. Palisca (ed.). Fundamentals of Music (PDF) (Translation of De institutione musica). Translated by Calvin M. Bower. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-03943-6 – via classicalliberalarts.com.

- Brandt, Anthony (2007). "Musical Form". Connexions (11 January; accessed 11 September 2011).[unreliable source?]

- Castan, Gerd (2009). "Musical Notation Codes". Music-Notation.info (Accessed 1 May 2010).

- Christiani, Adolph Friedrich (1885). The Principles of Expression in Pianoforte Playing. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Dahlhaus, Carl (2009). "Harmony". Grove Music Online, edited by Deane Root (reviewed 11 December; accessed 30 July 2015).

- Darwin, Charles (1913). The Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- Davies, Stephen (1994). Musical Meaning and Expression. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8151-2.

- d'Erlanger, Rodolphe (ed. and trans.) (1930–56). La Musique arabe, six volumes. Paris: P. Geuthner.

- Dunsby, Jonathan; Stopford, John (1981). "The Case for a Schenkerian Semiotic". Music Theory Spectrum. 3: 49–53. doi:10.2307/746133. JSTOR 746133.

- Ekwueme, Laz E. N. (1974). "Concepts of African Musical Theory". Journal of Black Studies 5, no. 1 (September): 35–64

- Forsyth, Cecil (1935). Orchestration, second edition. New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-24383-4.

- Garland, Trudi Hammel, and Charity Vaughan Kahn (1995). Math and Music: Harmonious Connections. Palo Alto: Dale Seymour Publications. ISBN 978-0-86651-829-1.

- Gerstner, Karl. 1964. Designing Programmes: Four Essays and an Introduction, with an introduction to the introduction by Paul Gredinger. English version by D. Q. Stephenson. Teufen, Switzerland: Arthur Niggli. Enlarged, new edition 1968.

- Ghrab, Anas (2009). "Commentaire anonyme du Kitāb al-Adwār. Édition critique, traduction et présentation des lectures arabes de l'œuvre de Ṣafī al-Dīn al-Urmawī". PhD thesis. Paris: University Paris-Sorbonne.

- Grant, M[orag] J[osephine] (2001). Serial Music, Serial Aesthetics: Compositional Theory in Post-War Europe. Music in the Twentieth Century, Arnold Whittall, general editor. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80458-2.

- Green, Douglass M. (1979). Form in Tonal Music. Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers; New York and London: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-03-020286-8.

- Hartmann, William M. (2005). Signals, Sound, and Sensation, corrected, fifth printing. Modern Acoustics and Signal Processing. Woodbury, New York: American Institute of Physics; New York: Springer. ISBN 1563962837.

- Jamini, Deborah (2005). Harmony and Composition: Basics to Intermediate, with DVD video. Victoria, BC: Trafford. 978-1-4120-3333-6.

- Károlyi, Otto (1965). Introducing Music.[full citation needed]: Penguin Books.

- Kilmer, Anne D. (1971). "The Discovery of an Ancient Mesopotamian Theory of Music". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society 115, no. 2:131–149.

- Kilmer, Anne, and Sam Mirelman. n.d. "Mesopotamia. 8. Theory and Practice". Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Accessed 13 November 2015. (subscription required)

- Kivy, Peter (1993). The Fine Art of Repetition: Essays in the Philosophy of Music. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press.ISBN 978-0-521-43462-1, 978-0-521-43598-7 (cloth & pbk).

- Kliewer, Vernon (1975). "Melody: Linear Aspects of Twentieth-Century Music". In Aspects of Twentieth-Century Music, edited by Gary Wittlich, 270–321. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0-13-049346-5.

- Kramer, Jonathan D. (1988). The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies. New York: Schirmer Books.

- Kubik, Gerhard (2010). Theory of African Music, 2 vols. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-45691-9.

- Kümmel, H. M. (1970). "Zur Stimmung der babylonischen Harfe". Orientalia 39:252–263.

- Lam, Joseph S. C. "China, §II, History and Theory". Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press.

- Latham, Alison (ed.) (2002). The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-866212-2.

- Laurie, Timothy (2014). "Music Genre as Method". Cultural Studies Review 20, no. 2:283–292.

- Lerdahl, Fred, and Ray Jackendoff (1985). A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press.ISBN 0262260913

- Lewin, David (1987). Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Linkels, Ad. n.d. "The Real Music of Paradise". In World Music, Vol. 2: Latin & North America, Caribbean, India, Asia and Pacific, edited by Simon Broughton and Mark Ellingham, with James McConnachie and Orla Duane, 218–229.[full citation needed]: Rough Guides, Penguin Books. ISBN 1-85828-636-0.

- London, Justin (2004). Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.[ISBN missing]

- London, Justin (n.d.), "Musical Expression and Musical Meaning in Context. ICMPC2000 Proceedings Papers.

- Lussy, Mathis (1892). Musical Expression: Accents, Nuances, and Tempo, in Vocal and Instrumental Music, translated by Miss M. E. von Glehn. Novello, Ewer, and Co.'s Music Primers 25. London: Novello, Ewer and Co.; New York: H. W. Gray

- McAdams, Stephen, and Albert Bregman (1979). "Hearing Musical Streams". Computer Music Journal 3, no. 4 (December): 26–43, 60. JSTOR 4617866

- McCreless, Patrick. n.d. "Society for Music Theory", Grove Music Online. Oxford University Press.

- Malm, William P. (1996). Music Cultures of the Pacific, the Near East, and Asia, third edition. ISBN 0-13-182387-6.

- Manik, Liberty (1969). Das Arabische Tonsystem im Mittelalter. Leiden: E. J. Brill.

- Mannell, Robert (n.d.). "Spectral Analysis of Sounds". Macquarie University.

- Meeùs, Nicolas (2015). "Épistémologie d’une musicologie analytique". Musurgia 22, nos. 3–4:97–114.

- Meeùs, Nicolas (2017). "Schenker's Inhalt, Schenkerian Semiotics. A Preliminary Study". The Dawn of Music Semiology. Essays in Honor of Jean-Jacques Nattiez, J. Dunsby and J. Goldman ed. Rochester: Rochester University Press:81–96.

- Middleton, Richard (1990). Studying Popular Music. Milton Keynes and Philadelphia: Open University Press. ISBN 978-0335152766, 978-0335152759 (cloth & pbk).

- Middleton, Richard (1999). "Form". In Key Terms in Popular Music and Culture, edited by Bruce Horner and Thomas Swiss.[page needed] Malden, Massachusetts: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 0-631-21263-9.

- Mirelman, Sam (2010). "A New Fragment of Music Theory from Ancient Iraq". Archiv für Musikwissenschaft 67, no. 1:45–51.

- Mirelman, Sam (2013). "Tuning Procedures in Ancient Iraq". Analytical Approaches to World Music 2, no. 2:43–56.

- Mitchell, Barry (2008). "An Explanation for the Emergence of Jazz (1956)", Theory of Music (16 January):[page needed].[unreliable source?]

- Moore, Allan F. (2001). "Categorical Conventions in Music Discourse: Style and Genre". Music & Letters 82, no. 3 (August): 432–442.

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1976). Fondements d'une sémiologie de la musique. Collection Esthétique. Paris: Union générale d'éditions. ISBN 978-2264000033.

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques(1989). Proust as Musician, translated by Derrick Puffett. Cambridge and New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-36349-5, 978-0-521-02802-8.

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990). Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music, translated by Carolyn Abbate of Musicologie generale et semiologie. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09136-5 (cloth); ISBN 978-0-691-02714-2 (pbk).

- "theory, n.1". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.)

- Palisca, Claude V., and Ian D. Bent. n.d. "Theory, Theorists". Grove Music Online, edited by Deane Root. Oxford University Press (accessed 17 December 2014).

- Purwins, Hendrik (2005). "Profiles of Pitch Classes Circularity of Relative Pitch and Key: Experiments, Models, Computational Music Analysis, and Perspectives". Doktor der Naturwissenschaften diss. Berlin: Technischen Universität Berlin.

- Read, Gardner (1969). Music Notation: A Manual of Modern Practice, second edition. Boston, Allyn and Bacon. Reprinted, London: Gollancz, 1974. ISBN 9780575017580. Reprinted, London: Gollancz, 1978. ISBN 978-0575025547. Reprinted, New York: Taplinger Publishing, 1979. ISBN 978-0800854591, 978-0800854539.

- Samson, Jim. "Genre". In Grove Music Online, edited by Deane Root. Oxford Music Online. Accessed 4 March 2012

- Schenker, Heinrich (1979). Free Composition. Translated and edited by Ernst Oster. New York and London, Longman.

- Schoenberg, Arnold (1983). Structural Functions of Harmony, revised edition with corrections, edited by Leonard Stein. London and Boston: Faber and Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-13000-9.

- Scholes, Percy A. (1977). "Form". The Oxford Companion to Music, tenth edition. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Service, Jonathan (2013). "Chinese Music Theory". Transmission/Transformation: Sounding China in Enlightenment Europe. Cambridge: Harvard University Department of Music (web, accessed 17 December 2015).

- Shiloah, Amnon (1964). La perfection des connaissances musicales: Traduction annotée du traité de musique arabe d'al-Ḥasan ibn Aḥmad ibn 'Ali al-Kātib École pratique des hautes études. 4e section, Sciences historiques et philologiques, Annuaire 1964–1965 97, no. 1: 451–456.

- Smith Brindle, Reginald (1987). The New Music: The Avant-Garde Since 1945, second edition. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-315471-1, 978-0-19-315468-1 (cloth & pbk).

- Snarrenberg, Robert (1997). Schenker's Interpretive Practice. Cambridge Studies in Music Theory and Analysis 11. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521497264.

- Sorantin, Erich (1932). The Problem of Musical Expression: A Philosophical and Psychological Study. Nashville: Marshall and Bruce

- Stefani, Gino (1973). "Sémiotique en musicologie". Versus 5:20–42.

- Stefani, Gino (1976). Introduzione alla semiotica della musica. Palermo: Sellerio editore.

- Stein, Leon (1979). Structure and Style: The Study and Analysis of Musical Forms. Princeton, New Jersey: Summy-Birchard Music. ISBN 978-0-87487-164-7.

- Stone, Kurt (1980). Music Notation in the Twentieth Century. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-95053-3.

- Tan, Siu-Lan, Pfordresher Peter, and Harré Rom (2010). Psychology of Music: From Sound to Significance. New York: Psychology Press. ISBN 978-1-84169-868-7.

- Thompson, William Forde (n.d.). Music, Thought, and Feeling: Understanding the Psychology of Music, second edition. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-537707-9.

- Touma, Habib Hassan (1996). The Music of the Arabs, new expanded edition, translated by Laurie Schwartz. Portland, Oregon: Amadeus Press. ISBN 0-931340-88-8.

- van der Merwe, Peter (1989). Origins of the Popular Style: The Antecedents of Twentieth-Century Popular Music. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 978-0-19-316121-4.

- Whittall, Arnold (2008). The Cambridge Introduction to Serialism. Cambridge Introductions to Music. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-86341-4, 978-0-521-68200-8 (cloth & pbk).

- Wohl, Gennady. (2005). "Algebra of Tonal Functions", translated by Mykhaylo Khramov. Sonantometry Blogspot (16 June; accessed 31 July 2015).[unreliable source?]

- Wong, Janice (2011). "Visualising Music: The Problems with Genre Classification". Masters of Media blog site (accessed 11 August 2015).[unreliable source?]

- Wright, Owen (2001a). "Munajjim, al- [Yaḥyā ibn]". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan. Reprinted in Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online. (subscription required).

- Wright, Owen (2001b). "Arab Music, §1: Art Music, 2. The Early Period (to 900 CE), (iv) Early Theory". The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan. Reprinted in Grove Music Online, Oxford Music Online. (subscription required).

- Wulstan, David (1968). "The Tuning of the Babylonian Harp". Iraq 30: 215–28.

- Yeston, Maury (1976). The Stratification of Musical Rhythm. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Further reading[edit]

- Anon. (2011). Job: Adjunct/Affiliate in Music Theory. Philadelphia: St Josephs University.

- Anon. (2014). "Full-time, Tenure-track Position in Music Theory, at the Rank of Assistant Professor, Beginning Fall 2014". Buffalo: University at Buffalo Department of Music.

- Anon. (2015). "College of William and Mary: Assistant Professor of Music, Theory and Composition (Tenure Eligible)". Job Listings, MTO (accessed 10 August 2015).

- Apel, Willi, and Ralph T. Daniel (1960). The Harvard Brief Dictionary of Music. New York: Simon & Schuster Inc. ISBN 0-671-73747-3

- Aristoxenus (1902). Aristoxenou Harmonika stoicheia: The Harmonics of Aristoxenus, Greek text edited with an English translation and notes by Henry Marcam. Oxford: The Clarendon Press.

- Bakkegard, B. M., and Elizabeth Ann Morris (1961). "Seventh Century Flutes from Arizona". Ethnomusicology 5, no. 3 (September): 184–186. doi:10.2307/924518.

- Bakshi, Haresh (2005). 101 Raga-s for the 21st Century and Beyond: A Music Lover's Guide to Hindustani Music. Victoria, British Columbia: Trafford. ISBN 978-1412046770, 978-1412231350 (ebook).

- Barnes, Latham (1984). The Complete Works of Aristotle. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-09950-2.

- Baur, John (2014). Practical Music Theory. Dubuque: Kendall-Hunt Publishing Company. ISBN 978-1-4652-1790-5

- Benade, Arthur H. (1960). Horns, Strings, and Harmony. Science Study Series S 11. Garden City, New York: Doubleday

- Bent, Ian D., and Anthony Pople (2001). "Analysis." The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians, second edition, edited by Stanley Sadie and John Tyrrell. London: Macmillan.

- Benward, Bruce, Barbara Garvey Jackson, and Bruce R. Jackson. (2000). Practical Beginning Theory: A Fundamentals Worktext, 8th edition, Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-697-34397-9. [First edition 1963]

- Benward, Bruce, and Marilyn Nadine Saker (2009). Music in Theory and Practice, eighth edition, vol. 2. Boston: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-310188-0.

- Billmeier, Uschi (1999). Mamady Keïta: A Life for the Djembé – Traditional Rhythms of the Malinké, fourth edition. Kirchhasel-Uhlstädt: Arun-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-935581-52-3.

- Boretz, Benjamin (1995). Meta-Variations: Studies in the Foundations of Musical Thought. Red Hook, New York: Open Space.

- Both, Arnd Adje (2009). "Music Archaeology: Some Methodological and Theoretical Considerations". Yearbook for Traditional Music 41:1–11. JSTOR 25735475