Dōgen Zenji (道元禅師; 26 January 1200 – 22 September 1253),[1][2] also known as Dōgen Kigen (道元希玄), Eihei Dōgen (永平道元), Kōso Jōyō Daishi (高祖承陽大師), or Busshō Dentō Kokushi (仏性伝東国師), was a Japanese Buddhist priest, writer, poet, philosopher, and founder of the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan.

Originally ordained as a monk in the Tendai School in Kyoto, he was ultimately dissatisfied with its teaching and traveled to China to seek out what he believed to be a more authentic Buddhism. He remained there for five years, finally training under Tiantong Rujing, an eminent teacher of the Chinese Caodong lineage. Upon his return to Japan, he began promoting the practice of zazen (sitting meditation) through literary works such as Fukan zazengi and Bendōwa.

He eventually broke relations completely with the powerful Tendai School, and, after several years of likely friction between himself and the establishment, left Kyoto for the mountainous countryside where he founded the monastery Eihei-ji, which remains the head temple of the Sōtō school today.

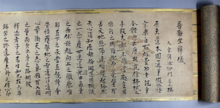

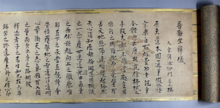

Dōgen is known for his extensive writing including his most famous work, the collection of 95 essays called the Shōbōgenzō, but also Eihei Kōroku, a collection of his talks, poetry, and commentaries, and Eihei Shingi, the first Zen monastic code written in Japan, among others.

Biography[edit]

Early life[edit]

Dōgen was probably born into a noble family, though as an illegitimate child of Minamoto Michitomo, who served in the imperial court as a high-ranking ashō (亞相, "Councillor of State").[3] His mother is said to have died when Dōgen was age 7.[4]

Early training[edit]

At some later point, Dōgen became a low-ranking monk on Mount Hiei, the headquarters of the Tendai school of Buddhism. According to the Kenzeiki (建撕記), he became possessed by a single question with regard to the Tendai doctrine:

As I study both the exoteric and the esoteric schools of Buddhism, they maintain that human beings are endowed with Dharma-nature by birth. If this is the case, why did the Buddhas of all ages — undoubtedly in possession of enlightenment — find it necessary to seek enlightenment and engage in spiritual practice?[5][6]

This question was, in large part, prompted by the Tendai concept of original enlightenment (本覚 hongaku), which states that all human beings are enlightened by nature and that, consequently, any notion of achieving enlightenment through practice is fundamentally flawed.[7]

The Kenzeiki further states that he found no answer to his question at Mount Hiei, and that he was disillusioned by the internal politics and need for social prominence for advancement.[3] Therefore, Dōgen left to seek an answer from other Buddhist masters. He went to visit Kōin, the Tendai abbot of Onjō-ji Temple (園城寺), asking him this same question. Kōin said that, in order to find an answer, he might want to consider studying Chán in China.[8] In 1217, two years after the death of contemporary Zen Buddhist Myōan Eisai, Dōgen went to study at Kennin-ji Temple (建仁寺), under Eisai's successor, Myōzen (明全).[3]

Travel to China[edit]

In 1223, Dōgen and Myōzen undertook the dangerous passage across the East China Sea to China to study in Jing-de-si (Ching-te-ssu, 景德寺) monastery as Eisai had once done.[citation needed]

In China, Dōgen first went to the leading Chan monasteries in Zhèjiāng province. At the time, most Chan teachers based their training around the use of gōng-àns (Japanese: kōan). Though Dōgen assiduously studied the kōans, he became disenchanted with the heavy emphasis laid upon them, and wondered why the sutras were not studied more. At one point, owing to this disenchantment, Dōgen even refused Dharma transmission from a teacher.[9] Then, in 1225, he decided to visit a master named Rújìng (如淨; J. Nyōjo), the thirteenth patriarch of the Cáodòng (J. Sōtō) lineage of Zen Buddhism, at Mount Tiāntóng (天童山 Tiāntóngshān; J. Tendōzan) in Níngbō. Rujing was reputed to have a style of Chan that was different from the other masters whom Dōgen had thus far encountered. In later writings, Dōgen referred to Rujing as "the Old Buddha". Additionally he affectionately described both Rujing and Myōzen as senshi (先師, "Ancient Teacher").[3]

Under Rujing, Dōgen realized liberation of body and mind upon hearing the master say, "Cast off body and mind" (身心脱落 shēn xīn tuō luò). This phrase would continue to have great importance to Dōgen throughout his life, and can be found scattered throughout his writings, as—for example—in a famous section of his "Genjōkōan" (現成公案):

To study the Way is to study the Self. To study the Self is to forget the self. To forget the self is to be enlightened by all things of the universe. To be enlightened by all things of the universe is to cast off the body and mind of the self as well as those of others. Even the traces of enlightenment are wiped out, and life with traceless enlightenment goes on forever and ever.[10]

Myōzen died shortly after Dōgen arrived at Mount Tiantong. In 1227,[11] Dōgen received Dharma transmission and inka from Rujing, and remarked on how he had finally settled his "life's quest of the great matter".[12]

Return to Japan[edit]

Dōgen returned to Japan in 1227 or 1228, going back to stay at Kennin-ji, where he had trained previously.[3] Among his first actions upon returning was to write down the Fukan Zazengi[13] (普観坐禅儀; "Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen"), a short text emphasizing the importance of and giving instructions for zazen, or sitting meditation.[14]

However, tension soon arose as the Tendai community began taking steps to suppress both Zen and Jōdo Shinshū, the new forms of Buddhism in Japan. In the face of this tension, Dōgen left the Tendai dominion of Kyōto in 1230, settling instead in an abandoned temple in what is today the city of Uji, south of Kyōto.[15] In 1233, Dōgen founded the Kannon-dōri-in[16] in Fukakusa as a small center of practice. He later expanded this temple into Kōshōhōrin-ji (興聖法林寺).[17]

Eihei-ji[edit]

In 1243, Hatano Yoshishige (波多野義重) offered to relocate Dōgen's community to Echizen province, far to the north of Kyōto. Dōgen accepted because of the ongoing tension with the Tendai community, and the growing competition of the Rinzai-school.[18]

His followers built a comprehensive center of practice there, calling it Daibutsu Temple (Daibutsu-ji, 大仏寺). While the construction work was going on, Dōgen would live and teach at Yoshimine-dera Temple (Kippō-ji, 吉峯寺), which is located close to Daibutsu-ji. During his stay at Kippō-ji, Dōgen "fell into a depression".[18] It marked a turning point in his life, giving way to "rigorous critique of Rinzai Zen".[18] He criticized Dahui Zonggao, the most influential figure of Song Dynasty Chán.[19]

In 1246, Dōgen renamed Daibutsu-ji, calling it Eihei-ji.[20] This temple remains one of the two head temples of Sōtō Zen in Japan today, the other being Sōji-ji.[21]

Dōgen spent the remainder of his life teaching and writing at Eihei-ji. In 1247, the newly installed shōgun's regent, Hōjō Tokiyori, invited Dōgen to come to Kamakura to teach him. Dōgen made the rather long journey east to provide the shōgun with lay ordination, and then returned to Eihei-ji in 1248. In the autumn of 1252, Dōgen fell ill, and soon showed no signs of recovering. He presented his robes to his main apprentice, Koun Ejō (孤雲懐弉), making him the abbot of Eihei-ji.[citation needed]

At Hatano Yoshishige's invitation, Dōgen left for Kyōto in search of a remedy for his illness. In 1253, soon after arriving in Kyōto, Dōgen died. Shortly before his death, he had written a death poem:

Fifty-four years lighting up the sky.

A quivering leap smashes a billion worlds.

Hah!

Entire body looks for nothing.

Living, I plunge into Yellow Springs.[22]

Miraculous events and auspicious signs[edit]

Several "miraculous experiences" and "auspicious signs" have been recorded in Dōgen's life,[note 1] some of them quite famous. According to Bodiford, "Monks and laymen recorded these events as testaments to his great mystical power," which "helped confirm the legacy of Dōgen's teachings against competing claims made by members of the Buddhist establishment and other outcast groups." Bodiford further notes that the "magical events at Eiheiji helped identify the temple as a cultic center," putting it at a par with other temples where supernatural events occurred. According to Faure, for Dōgen these auspicious signs were proof that "Eiheiji was the only place in Japan where the Buddhist Dharma was transmitted correctly and that this monastery was thus rivaled by no other."

In Menzan Zuihō's well-known 1753 edition of Dōgen's biography, it records that while traveling in China with his companion Dōshō, Dōgen became very ill, and a deity appeared before him who gave him medicine which instantly healed him:

Dōgen fell gravely ill on his way back from China but had no medicines that could be of use. Suddenly, an immortal appeared and gave Dōgen a herbal pill, after which he immediately became better. The master asked this deity to reveal its identity. The mysterious figure replied, “I am the Japanese kami Inari” and disappeared. The medicine became known as Gedokugan, which has been ever since been part of the Dōshō family heritage [...] Dōgen then told Dōshō that this rare and wondrous medicine had been bestowed on him by a true kami for the protection of the great Dharma, [and that] this medicine of many benefits should be distributed to temples so that they might spread the Dharma heritage.

This medicine, which later became known as Gedokuen or "Poison-Dispelling Pill" was then produced by the Sōtō church until the Meiji Era, and was commonly sold nationwide as an herbal medicine, and became a source of income for the Sōtō church.

The statue memorializing Dōgen's vision of Avalokiteshvara at a pond in Eihei-ji, Japan. Another famous incident happened when he was returning to Japan from China. The ship he was on was caught in a storm. In this instance, the storm became so severe, that the crew feared the ship would sink and kill them all. Dōgen then began leading the crew in recitation of chants to Kannon (Avalokiteshwara), during which, the Bodhisattva appeared before him, and several of the crew saw her as well. After the vision appeared, the storm began to calm down, and consensus of those aboard was that they had been saved due to the intervention of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshwara. This story is repeated in official works sponsored by the Sōtō Shū Head Office and there is even a sculpture of the event in a water treatment pond in Eihei-ji Temple. Additionally, there is a 14th-century copy of a painting of the same Kannon, that was supposedly commissioned by Dōgen, that includes a piece of calligraphy that is possibly an original in Dōgen's own hand, recording his gratitude to Avalokiteshwara:

From the single blossom five leaves uncurled: Upon one single leaf a Tathagata stood alone. Her vow to harmonize our lives is ocean deep, As we spin on and on, shouldering our deeds of right and wrong. –written by the mendicant monk Dōgen, September 26, 1242.

Another miraculous event occurred, while Dōgen was at Eihei-ji. During a ceremony of gratitude for the 16 Celestial Arahants (called Rakan in Japanese), a vision of 16 Arahants appeared before Dōgen descending upon a multi-colored cloud, and the statues of the Arahants that were present at the event began to emanate rays of light, to which Dōgen then exclaimed:

The Rakans caused to appear felicitous flowers, exceedingly wonderful and beautiful

Dōgen was profoundly moved by the entire experience, and took it as an auspicious sign that the offerings of the ceremony had been accepted. In his writings he wrote:

As for other examples of the appearance of auspicious signs, apart from [the case of] the rock bridge of Mount Tiantai, [in the province] of Taizhou, in the great kingdom of the Song, nowhere else to my knowledge has there been one to compare with this one. But on this mountain [Kichijōsan, the location of Eiheiji] many apparitions have already happened. This is truly a very auspicious sign showing that, in their deep compassion, [the Arahats] are protecting the men and the Dharma of this mountain. This is why it appeared to me.”

Dōgen is also recorded to have had multiple encounters with non-human beings. Aside from his encounter with the kami Inari in China, in the Denkōrou it is recorded that while at Kōshō-ji, he was also visited by a deva who came to observe during certain ceremonies, as well as a dragon who visited him at Eihei-Ji and requested to be given the eight abstinence Precepts:

When he was at Kōshō-ji a deva used to come to hear the Precepts and join in as an observer at the twice-monthly renewal of Bodhisattva vows. At Eihei-ji a divine dragon showed up requesting the eight Precepts of abstinence and asking to be included among the daily transfers of merit. Because of this Dōgen wrote out the eight Precepts every day and offered the merit thereof to the dragon. Up to this very day this practice has not been neglected.

Teachings[edit]

Dōgen often stressed the critical importance of zazen, or sitting meditation as the central practice of Buddhism. He considered zazen to be identical to studying Zen. This is pointed out clearly in the first sentence of the 1243 instruction manual "Zazen-gi" (坐禪儀; "Principles of Zazen"): "Studying Zen ... is zazen".[37] Dōgen taught zazen to everyone, even for the laity, male or female and including all social classes.[38] In referring to zazen, Dōgen is most often referring specifically to shikantaza, roughly translatable as "nothing but precisely sitting", or "just sitting," which is a kind of sitting meditation in which the meditator sits "in a state of brightly alert attention that is free of thoughts, directed to no object, and attached to no particular content".[39] In his Fukan Zazengi, Dōgen wrote:

For zazen, a quiet room is suitable. Eat and drink moderately. Cast aside all involvements and cease all affairs. Do not think good or bad. Do not administer pros and cons. Cease all the movements of the conscious mind, the gauging of all thoughts and views. Have no designs on becoming a Buddha. Zazen has nothing whatever to do with sitting or lying down.[40]

Dōgen called this zazen practice "without thinking" (hi-shiryo) in which one is simply aware of things as they are, beyond thinking and not-thinking - the active effort not to think.

The correct mental attitude for zazen according to Dōgen is one of effortless non-striving, this is because for Dōgen, enlightenment is already always present.

Further, Dōgen frequently distanced himself from more syncretic Buddhist practices at the time, including those of his contemporary Eisai. In the Bendowa, Dōgen writes:[41]

Commitment to Zen is casting off body and mind. You have no need for incense offerings, homage praying, nembutsu, penance disciplines, or silent sutra readings; just sit single-mindedly.

Oneness of practice-enlightenment[edit]

The primary concept underlying Dōgen's Zen practice is "oneness of practice-enlightenment" (修證一如 shushō-ittō / shushō-ichinyo).

For Dōgen, the practice of zazen and the experience of enlightenment were one and the same. This point was succinctly stressed by Dōgen in the Fukan Zazengi, the first text that he composed upon his return to Japan from China:

To practice the Way singleheartedly is, in itself, enlightenment. There is no gap between practice and enlightenment or zazen and daily life.[42]

Earlier in the same text, the basis of this identity is explained in more detail:

Zazen is not "step-by-step meditation". Rather it is simply the easy and pleasant practice of a Buddha, the realization of the Buddha's Wisdom. The Truth appears, there being no delusion. If you understand this, you are completely free, like a dragon that has obtained water or a tiger that reclines on a mountain. The supreme Law will then appear of itself, and you will be free of weariness and confusion.[43]

The "oneness of practice-enlightenment" was also a point stressed in the Bendōwa (弁道話 "A Talk on the Endeavor of the Path") of 1231:

Thinking that practice and enlightenment are not one is no more than a view that is outside the Way. In buddha-dharma [i.e. Buddhism], practice and enlightenment are one and the same. Because it is the practice of enlightenment, a beginner's wholehearted practice of the Way is exactly the totality of original enlightenment. For this reason, in conveying the essential attitude for practice, it is taught not to wait for enlightenment outside practice.[44]

Buddha-nature[edit]

For Dōgen, Buddha-nature or Busshō (佛性) is the nature of reality and all Being. In the Shōbōgenzō, Dōgen writes that "whole-being is the Buddha-nature" and that even inanimate objects (rocks, sand, water) are an expression of Buddha-nature. He rejected any view that saw Buddha-nature as a permanent, substantial inner self or ground. Dōgen held that Buddha-nature was "vast emptiness", "the world of becoming" and that "impermanence is in itself Buddha-nature".[45] According to Dōgen:

Therefore, the very impermanency of grass and tree, thicket and forest is the Buddha nature. The very impermanency of men and things, body and mind, is the Buddha nature. Nature and lands, mountains and rivers, are impermanent because they are the Buddha nature. Supreme and complete enlightenment, because it is impermanent, is the Buddha nature.[46]

Time-Being[edit]

Dōgen's conception of Being-Time or Time-Being (Uji, 有時) is an essential element of his metaphysics in the Shōbōgenzō. According to the traditional interpretation, "Uji" here means time itself is being, and all being is time."[47] Uji is all the changing and dynamic activities that exist as the flow of becoming, all beings in the entire world are time.[48] The two terms are thus spoken of concurrently to emphasize that the things are not to be viewed as separate concepts. Moreover, the aim is to not abstract time and being as rational concepts. This view has been developed by scholars such as Steven Heine,[49] Joan Stambaugh[50] and others and has served as a motivation to compare Dōgen's work to that of Martin Heidegger's "Dasein".[citation needed] Recently, however, Rein Raud has argued that this view is not correct and that Dōgen asserts that all existence is momentary, showing that such a reading would make quite a few of the rather cryptic passages in the Shōbōgenzō quite lucid.[51]

Perfect expression[edit]

Another essential element of Dōgen's 'performative' metaphysics is his conception of Perfect expression (Dōtoku, 道得).[52] "While a radically critical view on language as soteriologically inefficient, if not positively harmful, is what Zen Buddhism is famous for,"[53] it[clarification needed] can be argued "'within the framework of a rational theory of language, against an obscurantist interpretation of Zen that time and again invokes experience.'"[54] Dōgen distinguishes two types of language: monji 文字, the first, – after Ernst Cassirer – "discursive type that constantly structures our experiences and—more fundamentally—in fact produces the world we experience in the first place"; and dōtoku 道得, the second, "presentative type, which takes a holistic stance and establishes the totality of significations through a texture of relations.".[55] As Döll points out, "It is this second type, as Müller holds, that allows for a positive view of language even from the radically skeptical perspective of Dōgen’s brand of Zen Buddhism."[53]

Critique of Rinzai[edit]

Dōgen was sometimes critical of the Rinzai school for their formulaic and intellectual koan practice (such as the practice of the Shiryoken or "Four Discernments")[56] as well as for their disregard for the sutras:

Recently in the great Sung dynasty of China there are many who call themselves "Zen masters". They do not know the length and breadth of the Buddha-Dharma. They have heard and seen but little. They memorize two or three sayings of Lin Chi and Yun Men and think this is the whole way of the Buddha-Dharma. If the Dharma of the Buddha could be condensed in two or three sayings of Lin Chi and Yun Men, it would not have been transmitted to the present day. One can hardly say that Lin Chi and Yun Men are the Venerable ones of the Buddha-Dharma.[56]

Dōgen was also very critical of the Japanese Daruma school of Dainichi Nōnin.[citation needed]

Virtues[edit]

Dogen's perspective of virtue is discussed in the Shōbōgenzō text as something to be practiced inwardly so that it will manifest itself on the outside. In other words, virtue is something that is both internal and external in the sense that one can practice internal good dispositions and also the expression of these good dispositions.[57]

Writings[edit]

Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen (普勧坐禅儀, fukan zazengi) While it was customary for Buddhist works to be written in Chinese, Dōgen often wrote in Japanese, conveying the essence of his thought in a style that was at once concise, compelling, and inspiring. A master stylist, Dōgen is noted not only for his prose, but also for his poetry (in Japanese waka style and various Chinese styles). Dōgen's use of language is unconventional by any measure. According to Dōgen scholar Steven Heine: "Dogen's poetic and philosophical works are characterized by a continual effort to express the inexpressible by perfecting imperfectable speech through the creative use of wordplay, neologism, and lyricism, as well as the recasting of traditional expressions".[58]

Shōbōgenzō[edit]

Dōgen's masterpiece is the Shōbōgenzō, talks and writings collected together in ninety-five fascicles. The topics range from monastic practice, to the equality of women and men, to the philosophy of language, being, and time. In the work, as in his own life, Dōgen emphasized the absolute primacy of shikantaza and the inseparability of practice and enlightenment.[citation needed]

Shinji Shōbōgenzō[edit]

Dōgen also compiled a collection of 301 koans in Chinese without commentaries added. Often called the Shinji Shōbōgenzō (shinji: "original or true characters" and shōbōgenzō, variously translated as "the right-dharma-eye treasury" or "Treasury of the Eye of the True Dharma"). The collection is also known as the Shōbōgenzō Sanbyakusoku (The Three Hundred Verse Shōbōgenzō") and the Mana Shōbōgenzō, where mana is an alternative reading of shinji. The exact date the book was written is in dispute but Nishijima believes that Dogen may well have begun compiling the koan collection before his trip to China.[59] Although these stories are commonly referred to as kōans, Dōgen referred to them as kosoku (ancestral criteria) or innen (circumstances and causes or results, of a story). The word kōan for Dogen meant "absolute reality" or the "universal Dharma".[60]

Eihei Kōroku, Shōbōgenzō Zuimonki[edit]

Lectures that Dōgen gave to his monks at his monastery, Eihei-ji, were compiled under the title Eihei Kōroku, also known as Dōgen Oshō Kōroku (The Extensive Record of Teacher Dōgen's Sayings) in ten volumes. The sermons, lectures, sayings and poetry were compiled shortly after Dōgen's death by his main disciples, Koun Ejō (孤雲懐奘, 1198–1280), Senne, and Gien. There are three different editions of this text: the Rinnō-ji text from 1598, a popular version printed in 1672, and a version discovered at Eihei-ji in 1937, which, although undated, is believed to be the oldest extant version.[61] Another collection of his talks is the Shōbōgenzō Zuimonki (Gleanings from Master Dōgen's Sayings) in six volumes. These are talks that Dōgen gave to his leading disciple, Ejō, who became Dōgen's disciple in 1234. The talks were recorded and edited by Ejō.

Hōkojōki[edit]

The earliest work by Dōgen is the Hōkojōki (Memoirs of the Hōkyō Period). This one volume work is a collection of questions and answers between Dōgen and his Chinese teacher, Tiāntóng Rújìng (天童如淨; Japanese: Tendō Nyojō, 1162–1228). The work was discovered among Dōgen's papers by Ejō in 1253, just three months after Dōgen's death.[citation needed]

Other writings[edit]

Other notable writings of Dōgen are:

- Fukan-zazengi (普勧坐禅儀, General Advice on the Principles of Zazen), one volume; probably written immediately after Dōgen's return from China in 1227.

- Bendōwa (弁道話, "On the Endeavor of the Way"), written in 1231. This represents one of Dōgen's earliest writings and asserts the superiority of the practice of shikantaza through a series of questions and answers.

- Eihei shoso gakudō-yōjinshū (Advice on Studying the Way), one volume; probably written in 1234.

- Tenzo kyōkun (Instructions to the Chief Cook), one volume; written in 1237.

- Bendōhō (Rules for the Practice of the Way), one volume; written between 1244 and 1246.

Source:[62]

Shushō-gi[edit]

The concept of oneness of practice-enlightenment is considered so fundamental to Dōgen's variety of Zen — and, consequently, to the Sōtō school as a whole — that it formed the basis for the work Shushō-gi (修證儀), which was compiled in 1890 by Takiya Takushū (滝谷卓洲) of Eihei-ji and Azegami Baisen (畔上楳仙) of Sōji-ji as an introductory and prescriptive abstract of Dōgen's massive work, the Shōbōgenzō ("Treasury of the Eye of the True Dharma").[citation needed]

Lineage[edit]

Though Dogen emphasised the importance of the correct transmission of the Buddha dharma, as guaranteed by the line of transmission from Shakyamuni, his own transmission became problematic in the third generation. In 1267 Ejō retired as Abbot of Eihei-ji, giving way to Gikai, who was already favored by Dōgen. Gikai introduced esoteric elements into the practice. Opposition arose, and in 1272 Ejō resumed the position of abbot. Following Ejō's death in 1280, Gikai became abbot again, strengthened by the support of the military for magical practices.[63] Opposition arose again, and Gikai was forced to leave Eihei-ji. He was succeeded by Gien, who was first trained in the Daruma-school of Nōnin. His supporters designated him as the third abbot, rejecting the legitimacy of Gien.

- Koun Ejō, commentator on the Shōbōgenzō, and former Darumashū elder

- Giin, through Ejō

- Gikai, through Ejō

- Gien, through Ejō

- Senne, another commentator of the Shōbōgenzō.

Jakuen, a student of Rujing, who traced his lineage "directly back the Zen of the Song period",[64] established Hōkyō-ji, where a strict style of Zen was practised. Students of his played a role in the conflict between Giin and Gikai.

A notable successor of Dogen was Keizan (瑩山; 1268–1325), founder of Sōji-ji Temple and author of the Record of the Transmission of Light (傳光錄 Denkōroku), which traces the succession of Zen masters from Siddhārtha Gautama up to Keizan's own day. Together, Dōgen and Keizan are regarded as the founders of the Sōtō school in Japan.

See also[edit]

- Zen - 2009 Japanese biopic about the life of Dōgen

References[edit]

- ^ Dōgen at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Bodiford, William M. (2006). "Remembering Dōgen: Eiheiji and Dōgen Hagiography". The Journal of Japanese Studies. 32 (1): 1–21.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Bodiford (2008), pp. 22–36

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 19

- ^ Bodiford (2008), p. 22

- ^ Ōkubo (1966), p. 80

- ^ Abe (1992), pp. 19–20

- ^ Tanahashi 4

- ^ Tanahashi p.5

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 125

- ^ Tanahashi 6

- ^ Tanahashi (2005), p. 144

- ^ "Fukan zazengi" (PDF). www.stanford.edu.

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 38-40

- ^ Tanahashi 39

- ^ Tanahashi 7

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 40

- ^ Jump up to:a b c Dumoulin (2005b), p. 62

- ^ McRae (2003), p. 123

- ^ Kim (2004), p. 47

- ^ "Touring Venerable Temples of Soto Zen Buddhism in Japan Plan". SotoZen-Net. Retrieved 29 July 2021.

- ^ Quoted in Tanahashi, 219

- ^ Principles of Zazen Archived 16 December 2015 at the Wayback Machine; tr. Bielefeldt, Carl.

- ^ Dumoulin (2005b), Section 2, "Dogen" pp. 51-119

- ^ Kohn (1991), pp. 196–197

- ^ "Fukanzazengi: Universally Recommended Instructions for Zazen" (PDF). Zen Heart Sangha.

- ^ collcutt, Martin (1996). Five Mountains: The Rinzai Zen Monastic Institution in Medieval Japan. Harvard University Asia Center. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-0674304987.

- ^ Yukoi 47

- ^ Yukoi 46

- ^ Okumura (1997), p. 30

- ^ Dumoulin 82, 85

- ^ Dumoulin 85

- ^ "Uji: The Time-Being by Eihei Dogen" Translated by Dan Welch and Kazuaki Tanahashi from: The Moon in a Dewdrop; writings of Zen Master Dogen

- ^ Dumoulin 89

- ^ Existential and Ontological Dimensions of Time in Heidegger and Dogen, SUNY Press, Albany 1985

- ^ Impermanence is Buddha-Nature: Dogen's Understanding of Temporality, University of Hawaii Press, Honolulu 1990

- ^ Raud, Rein. "The Existential Moment: Re-reading Dōgen's theory of time". Philosophy East and West, vol.62 No.2, April 2012

- ^ Cf. Kim (2004) and more systematically based on a theory of symbols Müller (2013); reviewed by Steffen Döll in Philosophy East & West Volume 65, Number 2 April 2015 636–639.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Döll (2015), p. 637

- ^ Müller (2013), p. 25 cited after Döll (2015), p. 637

- ^ Döll (2015), 637, cf. Müller (2013), p. 231.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Dumoulin 65

- ^ Mikkelson, Douglas (2006). "Toward a Description of Dogen's Moral Virtues". Journal of Religious Ethics. 34 (2): 225–251. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9795.2006.00267.x.

- ^ Heine (1997), p. 67

- ^ Nishijima (2003), p. i

- ^ Yasutani (1996), p. 8

- ^ Kim (1987), pp. 236–237

- ^ See Kim (1987), Appendix B, pp. 243–247, for a more complete list of Dōgen's major writings.

- ^ Dumoulin (2005b), p. 135

- ^ Dumoulin (2005b), p. 138

Sources[edit]

- Abe, Masao (1992). Heine, Steven (ed.). A Study of Dōgen: His Philosophy and Religion. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-0838-4.

- Bodiford, William M. (2008). Soto Zen in Medieval Japan (Studies in East Asian Buddhism). University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-3303-9.

- Cleary, Thomas. Rational Zen: The Mind of Dogen Zenji. Boston: Shambhala Publications, Inc., 1992. ISBN 0-87773-973-0.

- DeVisser, M. W. (1923), The Arhats in China and Japan, Berlin: Oesterheld

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005a). Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 1: India and China. World Wisdom Books. ISBN 9780941532891.

- Dumoulin, Heinrich (2005b). Zen Buddhism: A History. Volume 2: Japan. World Wisdom Books. ISBN 9780941532907.

- Dōshū, Ōkubo (1969–70), Dōgen Zenji Zenshū (2 ed.), Tokyo: Chikuma Shobō

- Eihei-ji Temple Staff (1994), Sanshō, the Magazine of Eihei-ji Temple, vol. November, Fukui, Japan: Eihei-ji Temple Press

- Faure, Bernard (2000), Visions of Power. Imaging Medieval Japanese Buddhism, Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press

- Dogen. The Heart of Dogen's Shobogenzo. Tr. Waddell, Norman and Abe, Masao. Albany: SUNY Press, 2002. ISBN 0-7914-5242-5.

- Heine, Steven (1994). Dogen and the Koan Tradition: a Tale of Two Shobogenzo Texts. Albany, NY: SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-1773-7.

- Heine, Steven (1997). The Zen Poetry of Dogen: Verses from the Mountain of Eternal Peace. Boston, MA: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-8048-3107-9.

- Heine, Steven (2006). Did Dogen Go to China? What He Wrote and When He Wrote It. New York, NY: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-530592-0.

- Ishida, M (1964), Japanese Buddhist Prints, translated by Nearman, Hubert, New York: Abrams

- Kato, K (1994), "The Life of Zen Master Dōgen (Illustrated)", Zen Fountains, Taishōji Sōtō Mission, Hilo, Hawaii, by permission of the Sōtōshū Shūmuchō, Tokyo

- Kim, Hee-jin (2004) [1975, 1980, 1987]. Eihei Dogen, Mystical Realist. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0-86171-376-9.

- Kohn, Michael H. (1991). The Shambhala Dictionary of Buddhism and Zen. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-0-87773-520-5.

- LaFleur, William R.; ed. Dogen Studies. The Kuroda Institute, 1985. ISBN 0-8248-1011-2.

- MacPhillamy, Daizui; Roberson, Zenshō; Benson, Kōten; Nearman, Hubert (1997), "YUME: Visionary Experience in the Lives of Great Masters Dōgen and Keizan", The Journal of the Order of Buddhist Contemplatives, 12 (2)

- Leighton, Taigen Dan; Visions of Awakening Space and Time: Dogen and the Lotus Sutra. New York: Oxford University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-19-538337-9.

- Leighton, Taigen Dan; Zen Questions: Zazen, Dogen and the Spirit of Creative Inquiry. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2011. ISBN 978-0-86171-645-6.

- Leighton, Taigen Dan; Okumura, Shohaku; tr. Dogen's Extensive Record: A Translation of the Eihei Koroku. Boston: Wisdom Publications, 2010. ISBN 978-0-86171-670-8.

- Leighton, Taigen Dan. Dogen's Pure Standards for the Zen Community: A Translation of Eihei Shingi. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1996. ISBN 0-7914-2710-2.

- Masunaga, Reiho. A Primer of Soto Zen. University of Hawaii: East-West Center Press, 1978. ISBN 0-7100-8919-8.

- McRae, John (2003). Seeing Through Zen. Encounter, Transformation, and Genealogy in Chinese Chan Buddhism. The University Press Group Ltd. ISBN 9780520237988.

- Müller, Ralf (2013). Dōgens Sprachdenken: Historische und symboltheoretische Perspektiven [Dōgen's Language Thinking: Systematic Perspectives from History and the Theory of Symbols] (Welten der Philosophie [Worlds of Philosophy]). Freiburg: Verlag Karl Alber. ISBN 9783495486108.

- Okumura, Shohaku; Leighton, Taigen Daniel; et al.; tr. The Wholehearted Way: A Translation of Eihei Dogen's Bendowa with Commentary. Boston: Tuttle Publishing, 1997. ISBN 0-8048-3105-X.

- Ōkubo, Dōshū (1966). Dōgen Zenji-den no kenkyū [道元禅師伝の研究]. Chikuma shobō.

- Nishijima, Gudo (2003). M. Luetchford; J. Peasons (eds.). Master Dōgen's Shinji Shobogenzo, 301 Koan Stories. Windbell.

- Nishijima, Gudo & Cross, Chodo; tr. 'Master Dogen's Shobogenzo' in 4 volumes. Windbell Publications, 1994. ISBN 0-9523002-1-4 and Shōbōgenzō, Vol. 1-4, Numata Center for Buddhist Translation and Research, Berkeley 2007-2008, ISBN 978-1-886439-35-1, 978-1-886439-36-8, 978-1-886-439-37-5, 978-1-886439-38-2 PDF

- Tanahashi, Kazuaki; ed. Moon In a Dewdrop: Writings of Zen Master Dogen. New York: North Point Press, 1997. ISBN 0-86547-186-X.

- Tanahashi, Kazuaki (tr.); Loori, Daido (comm.) (2011). The True Dharma Eye. Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-1590304747.

- Williams, Duncan (1998), "Temples, Pharmacies, Traveling Salesmen, and Pilgrims: Buddhist Production and Distribution of Medicine in Edo Japan", Japanese Religion Bulletin Supplement, New Series, 23 (February)

- Williams, Duncan Ryūken (2005), The Other Side of Zen: A Social History of Sōtō Zen Buddhism in Tokugawa Japan, Princeton University Press

- Yokoi, Yūhō and Victoria, Daizen; tr. ed. Zen Master Dōgen: An Introduction with Selected Writings. New York: Weatherhill Inc., 1990. ISBN 0-8348-0116-7.

- Yasutani, Hakuun (1996). Flowers Fall: a Commentary on Zen Master Dōgen's Genjokoan. Boston, MA: Shambhala Publications. ISBN 978-1-57062-103-1.

External links[edit]

| Wikiquote has quotations related to Dōgen. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dogen. |

====

Zen (2009 film)

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to searchZen (禅) is a 2009 film directed by Banmei Takahashi and starring Nakamura Kantarō II as Dogen, and Yuki Uchida as Orin.[1][2] The story is based on the novel Eihei no kaze: Dōgen no shōgai written by Tetsuo Ōtani in 2001.[3]

The film is a biography of Dōgen Zenji, a Japanese Zen Buddhist teacher. After travelling to China to study, Dogen founded the Sōtō school of Zen in Japan. The Buddhist Film Foundation described it as "a poignant, in-depth, reverent and surprisingly moving portrait of Eihei Dogen."[4]

Reception[edit]

Russell Edwards of Variety described it as "The origins of a spiritual tradition are depicted with prerequisite solemnity and a pleasing veneer of arthouse showmanship."[5] Mark Schilling, writing for The Japan Times, gave the film three and a half stars and described it as a "rare serious film about this form of Buddhism, which has had a huge cultural influence but is little understood — let alone practiced — by ordinary Japanese."[6]

Release[edit]

The film premiered in Japan in 2009. The following year, it had its US debut at the International Buddhist Film Festival.[7] The film was released on DVD and includes a short documentary entitled The Zen of Dogen with Kazuaki Tanahashi.[8]

References[edit]

- ^ "Zen - Reviews, Movie Trailers, Cast & Crew. Movies at Film.com". Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ Ouellette, Kevin (15 May 2009). "DVD release - Zen (Amuse Soft Entertainment) available on 6/25/2009". Nippon Cinema. Retrieved 27 July 2010.

- ^ Giuliano Tani (2018). Cinestoria del Giappone : il Sol Levante attraverso i suoi film. Kappalab, 2018. ISBN 9788885457102.

- ^ "Zen". The Buddhist Film Foundation. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ "Zen". Variety. January 25, 2009. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ "Zen". The Japan Times. January 16, 2009. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ "IBFF Showcase 2010". The Buddhist Film Foundation. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

- ^ "New Film Zen, Now on DVD". The Buddhist Film Foundation. Retrieved September 23, 2015.

External links[edit]

====