2023/01/04

An Uncommon Collaboration: Introduction David Bohm and J. Krishnamurti

The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory - Bohm, David, Hiley, Basil J.

https://www.scribd.com/document/377928301/David-Bohm-the-Undivided-Universe-an-Ontological-Interpretation-of-Quantum-Theory

See this image

See this imageFollow the Author

David Bohm

Follow

The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory Hardcover – 7 October 1993

by David Bohm (Author), Basil J. Hiley (Author)

4.7 out of 5 stars 27 ratings

Kindle

$59.15Read with Our Free App

Hardcover

$210.00

First published in 1995. Bohm, one of the foremost scientific thinkers of our time, and Hiley present a completely original approach to quantum theory which will alter our understanding of the world and reveal that a century of modern physics needs to be reconsidered.

Frequently bought together

+

+

Total Price:$283.17

Add all three to Cart

Some of these items dispatch sooner than the others.

Show details

This item: The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theoryby David BohmHardcover

$210.00

Quantum Theoryby DAVID BOHMPaperback

$32.12

Causality and Chance in Modern Physicsby David BohmPaperback

$41.05

Popular titles by this author

Page 1 of 3Page 1 of 3

Previous page

The Ending of Time: Where Philosophy and Physics Meet

Jiddu Krishnamurti

4.6 out of 5 stars 128

Paperback

$35.95$35.95

Prime FREE Delivery

Temporarily out of stock.

Wholeness and the Implicate Order

David Bohm

4.6 out of 5 stars 283

Paperback

$28.25$28.25

Prime FREE Delivery

Quantum Implications: Essays in Honour of David Bohm

B. J. Hiley

4.8 out of 5 stars 6

Paperback

$67.99$67.99

Prime FREE DeliveryMonday, January 16

Thought as a System: Second edition

David Bohm

4.6 out of 5 stars 77

Paperback

$46.99$46.99

Prime FREE DeliveryMonday, January 16

Product description

Review

'This is a brilliant book, of great depth and originality. Every physicist and physics student who wants to understand quantum mechanics should read this book.' - Physics Today

'A remarkable piece of work.' - Times Higher Education Supplement

'One of the most important works on quantum theory to appear during the last twenty years.' - Journal of Consciousness Studies

'This is a rich and stimulating book. It is indispensable reading for anyone with a serious interest in the interpretation of quantum theory.' - John Polkinghorne

'You will be very impressed by this wise and deep book that will certainly broaden your horizens and start you thinking about many things you thought you were sure of.' - Science

'This book disturbs the reader, because the profound originality of its thinking differs so much from mainstream physics and from what the new age has made of physics. It could be that it will in the course of time disturb also the course of physics.' - Network

'An important, forward-looking book.' - New Scientist

From the Back Cover

In The Undivided Universe, Professor David Bohm, one of the foremost scientific thinkers of the day and one of the most distinguished physicists of his generation, presents a radically different approach to quantum theory. With Basil Hiley, his co-author and long-time colleague, an interpretation of quantum theory is developed which gives a clear, intuitive understanding of its meaning and in which there is a coherent notion of the reality of the universe without assuming a fundamental role for the human observer. With the aid of new concepts such as active information together with non-locality, a comprehensive account of all the basic features of quantum theory is provided, including the relativistic domain and quantum field theory. The new approach is contrasted with other commonly accepted interpretations and it is shown that paradoxical or unsatisfactory features of the other interpretations, such as the wave-particle duality and the collapse of the wave function, do not arise. Finally, on the basis of the new interpretation, the authors make suggestions that go beyond current quantum theory and they indicate areas in which quantum theory may be expected to break down in a way that will allow for a test.

About the Author

Bohm, David; Hiley, Basil J.

Read less

The Best of BookTok

Fiction highlights of 2022 Shop Now

Product details

Publisher : Routledge; 1st edition (7 October 1993)

Language : English

Hardcover : 412 pages

2,059 in Science Essays & Commentary (Books)

4.7 out of 5 stars 27 ratings

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Page 1 of 4Page 1 of 4

Previous page

Wholeness and the Implicate Order

David Bohm

4.6 out of 5 stars 283

Paperback

$28.25$28.25

Prime FREE Delivery

Thought as a System: Second edition

David Bohm

4.6 out of 5 stars 77

Paperback

$46.99$46.99

Prime FREE DeliveryMonday, January 16

Quantum Theory

DAVID BOHM

4.6 out of 5 stars 198

Paperback

$32.12$32.12

Get it 13 - 23 JanFREE Shipping

Causality and Chance in Modern Physics

David Bohm

4.9 out of 5 stars 10

Paperback

$41.05$41.05

Get it 13 - 23 JanFREE Shipping

Only 5 left in stock.

Sci Order And Creativity: A Dramatic New Look at the Creative Roots of Science and Life

D. Bohm

4.6 out of 5 stars 32

Paperback

$48.62$48.62

Get it 1 - 9 Feb$5.97 shipping

Customer reviews

4.7 out of 5 stars

Top reviews from other countries

Translate all reviews to English

James Slater

5.0 out of 5 stars Important workReviewed in the United Kingdom 🇬🇧 on 27 April 2020

Verified Purchase

historically important work

Report abuse

Danilo C.

5.0 out of 5 stars the individed universeReviewed in Italy 🇮🇹 on 25 May 2016

Verified Purchase

ben fatto e molto chiaro anche se scritto in inglese. Un bellissimo essmpio di divulagazione scientifica chiara in un campo difficile

Report abuse

Translate review to English

Amazon Customer

5.0 out of 5 stars Lots of math, but has some essential insights into QMReviewed in the United States 🇺🇸 on 11 February 2020

Verified Purchase

Mostly beyond my skillset, but I'll get through it some day.

5 people found this helpfulReport abuse

G. Conger

5.0 out of 5 stars D. Bohm was way ahead of his time. ...Reviewed in the United States 🇺🇸 on 28 November 2015

Verified Purchase

D. Bohm was way ahead of his time. Someday he will receive his recognition. I am guessing another 20-30 years.

His ideas are difficult if not impossible for us to prove.

G

5 people found this helpfulReport abuse

Richard Decker

5.0 out of 5 stars Five StarsReviewed in the United States 🇺🇸 on 29 January 2018

Verified Purchase

Great book about quantum theory and how it implies the interconnectedness of everything.

3 people found this helpfulReport abuse

See all reviews

The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory

David Bohm, Basil Hiley

4.33

106 ratings12 reviews

This text develops an interpretation of quantum mechanics which provides a clear understanding of its meaning and in which there is a coherent notion of the reality of the universe without assuming a fundamental role for the human observer. With the aid o

GenresSciencePhysicsPhilosophyNonfictionQuantum MechanicsReferenceTechnical

...more

ebook

First published January 1, 1993

Book details & editions

About the author

David Bohm44 books351 followers

Follow

David Joseph Bohm (December 20, 1917 – October 27, 1992) was an American scientist who has been described as one of the most significant theoretical physicists of the 20th century and who contributed innovative and unorthodox ideas to quantum theory, neuropsychology and the philosophy of mind.

Readers also enjoyedPage 1 of 2

Displaying 1 - 10 of 12 reviews

Jason

4 reviews · 4 followers

Follow

September 3, 2012

I have been working up to being able to read this book from cover to cover, and at least have some idea of what the most technical sections are arguing, since I first started studying Bohm's ideas in the late 1980s.

If one can get through the complex physics context of his insights, I believe he expresses a revolutionary degree of sanity and simplicity.

Everything belongs and makes sense in Bohm's model. The classical worldview is a limiting condition already contained in the quantum model, not an external to be presupposed and grappled with for historical reasons. Quantum processes occur independent of observations. Time doesn't flow backwards as in Feynman Diagrams, or delayed choice experiments. Non-locality like the EPR experiments is the rule, not the exception. Mind and Matter are both expressions of the same implicit holistic flow, not opposed to each other or separated arbitrarily.

In short, this book makes a highly articulate case for an ontological holism that has the ability to make intuitive, graspable, (simple in its own way) sense of the physical world and Everything.

It is worth reading even for the physics novice. It is about a lot more than re-framing contemporary quantum mechanics with a more intuitive paradigm. It is intensely consistent and coherent in its approach to all of experience, and treats physical theory and mathematics as descriptive of an ever-evolving horizon of our total understanding.

11 likes

Like

Comment

Dolf van der Haven

15 books · 10 followers

Follow

August 10, 2020

Not the introductory text in quantum mechanics I thought it was - this is an advanced textbook! Bohm gives an ontological interpretation of QM, rather than the epistemological interpretation most physicists give, the latter limiting the possibilities of the theory. Bohm also repeats his theory of the implicate order, forst described in Wholeness and the Implicate Order. This book stays much closer to physics and mathematics, though, and is therefore harder to read. Bohm's theory is still tentative, carefully involving consciousness into QM, but is a much healthier alternative to the abuse many New Agers make of quantum theory.

2 likes

Like

Comment

Chris Marks

35 reviews · 4 followers

Follow

November 7, 2018

Remarkable. I do not understand why Bohm's ideas are not more widely accepted and appreciated. Bohmian mechanics explains much at little cost.

2 likes

Like

Comment

Brian

2 books · 35 followers

Follow

December 11, 2017

Bohm and Hiley make an argument for a new interpretation of quantum mechanics in which the hypothetical models calculated to account for experimental observations correspond to actually-occurring processes, rather than simply mathematical abstractions used to facilitate accurate predictions. This interpretation leads them to suggest that the quantum field comprises a pool of non-locally communicating information which informs the behavior of classically observable fields and particles. They address the implications of their interpretation for quantum theory's a priori hypotheses as well as its experimental results, and show that they arrive at results identical to those of traditional interpretations. Their proofs do make heavy use of the algebraic equations particular to quantum theory, but as long as one already has some grasp of the concepts and notation of such representations it is possible to comprehend their conclusions, if not follow all of their arguments in line-by-line detail.

Like

Comment

Ign33l

211 reviews

Follow

May 21, 2022

Lol 3 years after i have finished this book. It was because before i was weak and could not understand at all what this was giving me. Many formulas had to watch videos to understand physics, but now i have finished it and helped me align myself with the universe better. It showed me the dimension of where i am and how it is represented in the space and all the elements that cause interaction in it.

Also made me a better person to break some barriers that were not allowing my quantums to keep onmoving amd helped me understand how my particles can keep creating energy and communicate with the world.

Like

Comment

Matt

76 reviews · 16 followers

Follow

Shelved as 'to-read-soon'February 17, 2020

I have loved this book because the ideas it addresses are very interesting. More physicists today should consider these ideas seriously and think in ontological terms. Quantum mechanics becomes much more intuitive under Bohm's interpretation.

However, the material is very dense. I have only made it to page 232. I am putting the book down for a while, just because it is dense and I don't have as much time to read as I would like. I am putting it down only until I have some more free time again, and plan to finish it then. Again, this has nothing to do with the quality of the material.

physics

Like

Comment

Preston

10 reviews

Follow

May 16, 2020

As a theoretical chemist whose dissertation was on applications and further development of the Quantum Theory of Atoms IN Molecules (the most rigorous partitioning of matter), Bohm’s UNdivided universe is literally the opposite paradigm from what I have been accustomed to. For that reason alone it drew me in, like a moth to a flame. What new secrets does it hold?

Like

Comment

Mitch Allen

114 reviews · 7 followers

Follow

January 11, 2014

Bohm's ambitious book—his last, published after his death—attempts to prove his quantum theory mathematically and show that it is the most complete theory for the moment. He subsumes the common theory by providing a model for a holistic, quantum universe, not merely predicting experimental results, and shows that the classical physics world is a sub-world of a quantum one. The mathematics can be difficult for the non-technical reader, but overall some very intriguing stuff, particularly his digressions into consciousness and his explanations for classical dynamics as a function of quantum dynamics.

Like

Comment

Michael

79 reviews · 7 followers

Follow

January 29, 2017

The quantum potential paradigm is neat; but like every other quantum mechanics book I've read, this one discusses a lot of meta-physics.

Also, it's obvious that Hiley rushed the book through the publisher after Bohm died to keep the Bohm name on the cover. It could have used some more editing.

Like

Comment

DJ

317 reviews · 226 followers

Follow

Want to readJuly 24, 2009

referenced in "Nontrivial quantum effects in biology" by Wiseman and Eisert

3 comments

Like

Comment

Displaying 1 - 10 of 12 reviews

David Bohm - Wikipedia

David Bohm

David Bohm | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 20 December 1917 |

| Died | 27 October 1992 (aged 74) London, England, UK |

| Nationality | American-British |

| Citizenship |

|

| Alma mater | |

| Known for |

|

| Awards | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Theoretical physics |

| Institutions | |

| Doctoral advisor | Robert Oppenheimer |

| Doctoral students | |

| Influences | Albert Einstein Jiddu Krishnamurti |

| Influenced | John Stewart Bell, Peter Senge |

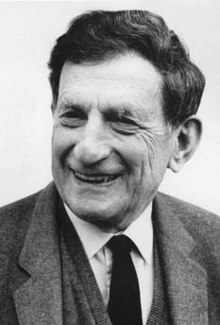

David Joseph Bohm FRS[1] (/boʊm/; 20 December 1917 – 27 October 1992) was an American-Brazilian-British scientist who has been described as one of the most significant theoretical physicists of the 20th century[2]

and who contributed unorthodox ideas to quantum theory, neuropsychology and the philosophy of mind.

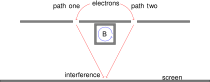

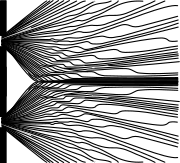

Among his many contributions to physics is his causal and deterministic interpretation of quantum theory, now known as De Broglie–Bohm theory.

Bohm advanced the view that quantum physics meant that the old Cartesian model of reality—that there are two kinds of substance, the mental and the physical, that somehow interact—was too limited. To complement it, he developed a mathematical and physical theory of "implicate" and "explicate" order.[3]

He also believed that the brain, at the cellular level, works according to the mathematics of some quantum effects, and postulated that thought is distributed and non-localised just as quantum entities are.[4][failed verification]

Bohm's main concern was with understanding the nature of reality in general and of consciousness in particular as a coherent whole, which according to Bohm is never static or complete.[5]

Bohm warned of the dangers of rampant reason and technology, advocating instead the need for genuine supportive dialogue, which he claimed could broaden and unify conflicting and troublesome divisions in the social world. In this, his epistemology mirrored his ontology.[6]

Born in the United States, Bohm obtained his Ph.D. under J. Robert Oppenheimer at the University of California, Berkeley. Due to his Communist affiliations, he was the subject of a federal government investigation in 1949, prompting him to leave the U.S. He pursued his career in several countries, becoming first a Brazilian and then a British citizen. He abandoned Marxism in the wake of the Hungarian Uprising in 1956.[7][8]

Contents

- 1Youth and college

- 2Work and doctorate

- 2.1Manhattan Project contributions

- 2.2McCarthyism and leaving the United States

- 2.3Quantum theory and Bohm diffusion

- 2.4Brazil

- 2.5Bohm and Aharonov form of the EPR paradox

- 2.6Aharonov–Bohm effect

- 2.7Implicate and explicate order

- 2.8Holonomic model of the brain

- 2.9Consciousness and thought

- 2.10Further interests

- 2.11Bohm dialogue

- 3Later life

- 4Reception of causal theory

- 5Publications

- 6See also

- 7References

- 8Sources

- 9Further reading

- 10External links

Youth and college[edit]

Bohm was born in Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, to a Hungarian Jewish immigrant father, Samuel Bohm,[9] and a Lithuanian Jewish mother. He was raised mainly by his father, a furniture-store owner and assistant of the local rabbi. Despite being raised in a Jewish family, he became an agnostic in his teenage years.[10] Bohm attended Pennsylvania State College (now Pennsylvania State University), graduating in 1939, and then the California Institute of Technology, for one year. He then transferred to the theoretical physics group directed by Robert Oppenheimer at the University of California, Berkeley Radiation Laboratory, where he obtained his doctorate.

Bohm lived in the same neighborhood as some of Oppenheimer's other graduate students (Giovanni Rossi Lomanitz, Joseph Weinberg, and Max Friedman) and with them became increasingly involved in radical politics. He was active in communist and communist-backed organizations, including the Young Communist League, the Campus Committee to Fight Conscription, and the Committee for Peace Mobilization. During his time at the Radiation Laboratory, Bohm was in a relationship with the future Betty Friedan and also helped to organize a local chapter of the Federation of Architects, Engineers, Chemists and Technicians, a small labor union affiliated to the Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO).[11]

Work and doctorate[edit]

Manhattan Project contributions[edit]

During World War II, the Manhattan Project mobilized much of Berkeley's physics research in the effort to produce the first atomic bomb. Though Oppenheimer had asked Bohm to work with him at Los Alamos (the top-secret laboratory established in 1942 to design the atom bomb), the project's director, Brigadier General Leslie Groves, would not approve Bohm's security clearance after seeing evidence of his politics and his close friendship with Weinberg, who had been suspected of espionage.

During the war, Bohm remained at Berkeley, where he taught physics and conducted research in plasma, the synchrotron and the synchrocyclotron. He completed his PhD in 1943 by an unusual circumstance. According to biographer F. David Peat,[12] "The scattering calculations (of collisions of protons and deuterons) that he had completed proved useful to the Manhattan Project and were immediately classified. Without security clearance, Bohm was denied access to his own work; not only would he be barred from defending his thesis, he was not even allowed to write his own thesis in the first place!" To satisfy the University, Oppenheimer certified that Bohm had successfully completed the research. Bohm later performed theoretical calculations for the Calutrons at the Y-12 facility in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, which was used for the electromagnetic enrichment of uranium for the bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945.

McCarthyism and leaving the United States[edit]

After the war, Bohm became an assistant professor at Princeton University. He also worked closely with Albert Einstein at the nearby Institute for Advanced Study. In May 1949, the House Un-American Activities Committee called upon Bohm to testify because of his previous ties to unionism and suspected communists. Bohm invoked his Fifth Amendment right to refuse to testify, and he refused to give evidence against his colleagues.

In 1950, Bohm was arrested for refusing to answer the committee's questions. He was acquitted in May 1951, but Princeton had already suspended him. After his acquittal, Bohm's colleagues sought to have him reinstated at Princeton, but Princeton President Harold W. Dodds[13] decided not to renew Bohm's contract. Although Einstein considered appointing him as his research assistant at the Institute, Oppenheimer (who had served as the Institute's president since 1947) "opposed the idea and [...] advised his former student to leave the country".[14] His request to go to the University of Manchester received Einstein's support but was unsuccessful.[15] Bohm then left for Brazil to assume a professorship of physics at the University of São Paulo, at Jayme Tiomno's invitation and on the recommendation of both Einstein and Oppenheimer.

Quantum theory and Bohm diffusion[edit]

During his early period, Bohm made a number of significant contributions to physics, particularly quantum mechanics and relativity theory. As a postgraduate at Berkeley, he developed a theory of plasmas, discovering the electron phenomenon now known as Bohm diffusion.[17] His first book, Quantum Theory, published in 1951, was well received by Einstein, among others. But Bohm became dissatisfied with the orthodox interpretation of quantum theory he wrote about in that book. Starting from the realization that the WKB approximation of quantum mechanics leads to deterministic equations and convinced that a mere approximation could not turn a probabilistic theory into a deterministic theory, he doubted the inevitability of the conventional approach to quantum mechanics.[18]

Bohm's aim was not to set out a deterministic, mechanical viewpoint but to show that it was possible to attribute properties to an underlying reality, in contrast to the conventional approach.[19] He began to develop his own interpretation (the De Broglie–Bohm theory, also called the pilot wave theory), the predictions of which agreed perfectly with the non-deterministic quantum theory. He initially called his approach a hidden variable theory, but he later called it ontological theory, reflecting his view that a stochastic process underlying the phenomena described by his theory might one day be found. Bohm and his colleague Basil Hiley later stated that they had found their own choice of terms of an "interpretation in terms of hidden variables" to be too restrictive, especially since their variables, position, and momentum "are not actually hidden".[20]

Bohm's work and the EPR argument became the major factor motivating John Stewart Bell's inequality, which rules out local hidden variable theories; the full consequences of Bell's work are still being investigated.

Brazil[edit]

After Bohm's arrival in Brazil on 10 October 1951, the US Consul in São Paulo confiscated his passport, informing him he could retrieve it only to return to his country, which reportedly frightened Bohm[21] and significantly lowered his spirits, as he had hoped to travel to Europe. He applied for and received Brazilian citizenship, but by law, had to give up his US citizenship; he was able to reclaim it only decades later, in 1986, after pursuing a lawsuit.[22]

At the University of São Paulo, Bohm worked on the causal theory that became the subject of his publications in 1952. Jean-Pierre Vigier traveled to São Paulo, where he worked with Bohm for three months; Ralph Schiller, student of cosmologist Peter Bergmann, was his assistant for two years; he worked with Tiomno and Walther Schützer; and Mario Bunge stayed to work with him for one year. He was in contact with Brazilian physicists Mário Schenberg, Jean Meyer, Leite Lopes, and had discussions on occasion with visitors to Brazil, including Richard Feynman, Isidor Rabi, Léon Rosenfeld, Carl Friedrich von Weizsäcker, Herbert L. Anderson, Donald Kerst, Marcos Moshinsky, Alejandro Medina, and the former assistant to Heisenberg, Guido Beck, who encouraged him in his work and helped him to obtain funding. The Brazilian CNPq explicitly supported his work on the causal theory and funded several researchers around Bohm. His work with Vigier was the beginning of a long-standing cooperation between the two and Louis De Broglie, in particular, on connections to the hydrodynamics model proposed by Madelung.[23] Yet the causal theory met much resistance and skepticism, with many physicists holding the Copenhagen interpretation to be the only viable approach to quantum mechanics.[22]

From 1951 to 1953, Bohm and David Pines published the articles in which they introduced the random phase approximation and proposed the plasmon.[24][25][26]

Bohm and Aharonov form of the EPR paradox[edit]

In 1955 Bohm relocated to Israel, where he spent two years working at the Technion, at Haifa. There, he met Sarah ("Saral") Woolfson, whom he married in 1956.

In 1957, Bohm and his student Yakir Aharonov published a new version of the Einstein–Podolsky–Rosen (EPR) paradox, reformulating the original argument in terms of spin.[27] It was that form of the EPR paradox that was discussed by John Stewart Bell in his famous paper of 1964.[28]

Aharonov–Bohm effect[edit]

In 1957, Bohm relocated to the United Kingdom as a research fellow at the University of Bristol. In 1959, Bohm and Aharonov discovered the Aharonov–Bohm effect, showing how a magnetic field could affect a region of space in which the field had been shielded, but its vector potential did not vanish there. That showed for the first time that the magnetic vector potential, hitherto a mathematical convenience, could have real physical (quantum) effects.

In 1961, Bohm was made professor of theoretical physics at the University of London's Birkbeck College, becoming emeritus in 1987. His collected papers are stored there.[29]

Implicate and explicate order[edit]

At Birkbeck College, much of the work of Bohm and Basil Hiley expanded on the notion of implicate, explicate, and generative orders proposed by Bohm.[3][30][31] In the view of Bohm and Hiley, "things, such as particles, objects, and indeed subjects" exist as "semi-autonomous quasi-local features" of an underlying activity. Such features can be considered to be independent only up to a certain level of approximation in which certain criteria are fulfilled. In that picture, the classical limit for quantum phenomena, in terms of a condition that the action function is not much greater than Planck's constant, indicates one such criterion. They used the word "holomovement" for the activity in such orders.[32]

Holonomic model of the brain[edit]

In collaboration with Stanford University neuroscientist Karl H. Pribram, Bohm was involved in the early development of the holonomic model of the functioning of the brain, a model for human cognition that is drastically different from conventionally-accepted ideas.[4][failed verification] Bohm worked with Pribram on the theory that the brain operates in a manner that is similar to a hologram, in accordance with quantum mathematical principles and the characteristics of wave patterns.[33]

Consciousness and thought[edit]

In addition to his scientific work, Bohm was deeply interested in exploring the nature of consciousness, with particular attention to the role of thought as it relates to attention, motivation, and conflict in the individual and in society.

Those concerns were a natural extension of his earlier interest in Marxist ideology and Hegelian philosophy.

His views were brought into sharper focus through extensive interactions with the philosopher, speaker, and writer Jiddu Krishnamurti, beginning in 1961.[34][35] Their collaboration lasted a quarter of a century, and their recorded dialogues were published in several volumes.[36][37][38]

Bohm's prolonged involvement with the philosophy of Krishnamurti was regarded somewhat skeptically by some of his scientific peers.[39][40] A more recent and extensive examination of the relationship between the two men presents it in a more positive light and shows that Bohm's work in the psychological field was complementary to and compatible with his contributions to theoretical physics.[35]

The mature expression of Bohm's views in the psychological field was presented in a seminar conducted in 1990 at the Oak Grove School, founded by Krishnamurti in Ojai, California. It was one of a series of seminars held by Bohm at Oak Grove School, and it was published as Thought as a System.[41] In the seminar, Bohm described the pervasive influence of thought throughout society, including the many erroneous assumptions about the nature of thought and its effects in daily life.

In the seminar, Bohm develops several interrelated themes. He points out that thought is the ubiquitous tool that is used to solve every kind of problem: personal, social, scientific, and so on. Yet thought, he maintains, is also inadvertently the source of many of those problems. He recognizes and acknowledges the irony of the situation: it is as if one gets sick by going to the doctor.[35][41]

Bohm maintains that thought is a system, in the sense that it is an interconnected network of concepts, ideas and assumptions that pass seamlessly between individuals and throughout society. If there is a fault in the functioning of thought, therefore, it must be a systemic fault, which infects the entire network. The thought that is brought to bear to resolve any given problem, therefore, is susceptible to the same flaw that created the problem it is trying to solve.[35][41]

Thought proceeds as if it is merely reporting objectively, but in fact, it is often coloring and distorting perception in unexpected ways. What is required in order to correct the distortions introduced by thought, according to Bohm, is a form of proprioception, or self-awareness. Neural receptors throughout the body inform us directly of our physical position and movement, but there is no corresponding awareness of the activity of thought. Such an awareness would represent psychological proprioception and would enable the possibility of perceiving and correcting the unintended consequences of the thinking process.[35][41]

Further interests[edit]

In his book On Creativity, quoting Alfred Korzybski, the Polish-American who developed the field of General Semantics, Bohm expressed the view that "metaphysics is an expression of a world view" and is "thus to be regarded as an art form, resembling poetry in some ways and mathematics in others, rather than as an attempt to say something true about reality as a whole".[42]

Bohm was keenly aware of various ideas outside the scientific mainstream. In his book Science, Order and Creativity, Bohm referred to the views of various biologists on the evolution of the species, including Rupert Sheldrake.[43] He also knew the ideas of Wilhelm Reich.[44]

Contrary to many other scientists, Bohm did not exclude the paranormal out of hand. Bohm temporarily even held Uri Geller's bending of keys and spoons to be possible, prompting warning remarks by his colleague Basil Hiley that it might undermine the scientific credibility of their work in physics. Martin Gardner reported this in a Skeptical Inquirer article and also critiqued the views of Jiddu Krishnamurti, with whom Bohm had met in 1959 and had had many subsequent exchanges. Gardner said that Bohm's view of the interconnectedness of mind and matter (on one occasion, he summarized: "Even the electron is informed with a certain level of mind."[45]) "flirted with panpsychism".[40]

Bohm dialogue[edit]

To address societal problems during his later years, Bohm wrote a proposal for a solution that has become known as "Bohm Dialogue", in which equal status and "free space" form the most important prerequisites of communication and the appreciation of differing personal beliefs. An essential ingredient in this form of dialogue is that participants "suspend" immediate action or judgment and give themselves and each other the opportunity to become aware of the thought process itself. Bohm suggested that if the "dialogue groups" were experienced on a sufficiently-wide scale, they could help overcome the isolation and fragmentation that Bohm observed in society.

Later life[edit]

Bohm continued his work in quantum physics after his retirement, in 1987. His final work, the posthumously published The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory (1993), resulted from a decades-long collaboration with Basil Hiley. He also spoke to audiences across Europe and North America on the importance of dialogue as a form of sociotherapy, a concept he borrowed from London psychiatrist and practitioner of Group Analysis Patrick de Maré, and he had a series of meetings with the Dalai Lama. He was elected Fellow of the Royal Society in 1990.[1]

Near the end of his life, Bohm began to experience a recurrence of the depression that he had suffered earlier in life. He was admitted to the Maudsley Hospital in South London on 10 May 1991. His condition worsened and it was decided that the only treatment that might help him was electroconvulsive therapy. Bohm's wife consulted psychiatrist David Shainberg, Bohm's longtime friend and collaborator, who agreed that electroconvulsive treatments were probably his only option. Bohm showed improvement from the treatments and was released on 29 August, but his depression returned and was treated with medication.[46]

Bohm died after suffering a heart attack in Hendon, London, on 27 October 1992, aged 74.[47]

The film Infinite Potential is based on Bohm's life and studies; it adopts the same name as the biography by F. David Peat.[48]

Reception of causal theory[edit]

In the early 1950s, Bohm's causal quantum theory of hidden variables was mostly negatively received, with a widespread tendency among physicists to systematically ignore both Bohm personally and his ideas. There was a significant revival of interest in Bohm's ideas in the late 1950s and the early 1960s; the Ninth Symposium of the Colston Research Society in Bristol in 1957 was a key turning point toward greater tolerance of his ideas.[49]

Publications[edit]

- 1951. Quantum Theory, New York: Prentice Hall. 1989 reprint, New York: Dover, ISBN 0-486-65969-0

- 1957. Causality and Chance in Modern Physics, 1961 Harper edition reprinted in 1980 by Philadelphia: U of Pennsylvania Press, ISBN 0-8122-1002-6

- 1962. Quanta and Reality, A Symposium, with N. R. Hanson and Mary B. Hesse, from a BBC program published by the American Research Council

- 1965. The Special Theory of Relativity, New York: W.A. Benjamin.

- 1980. Wholeness and the Implicate Order, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-7100-0971-2, 1983 Ark paperback: ISBN 0-7448-0000-5, 2002 paperback: ISBN 0-415-28979-3

- 1985. Unfolding Meaning: A weekend of dialogue with David Bohm (Donald Factor, editor), Gloucestershire: Foundation House, ISBN 0-948325-00-3, 1987 Ark paperback: ISBN 0-7448-0064-1, 1996 Routledge paperback: ISBN 0-415-13638-5

- 1985. The Ending of Time, with Jiddu Krishnamurti, San Francisco: Harper, ISBN 0-06-064796-5.

- 1987. Science, Order, and Creativity, with F. David Peat. London: Routledge. 2nd ed. 2000. ISBN 0-415-17182-2.

- 1989. Meaning And Information, In: P. Pylkkänen (ed.): The Search for Meaning: The New Spirit in Science and Philosophy, Crucible, The Aquarian Press, 1989, ISBN 978-1-85274-061-0.

- 1991. Changing Consciousness: Exploring the Hidden Source of the Social, Political and Environmental Crises Facing our World (a dialogue of words and images), coauthor Mark Edwards, Harper San Francisco, ISBN 0-06-250072-4

- 1992. Thought as a System (transcript of seminar held in Ojai, California, from 30 November to 2 December 1990), London: Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11980-4.

- 1993. The Undivided Universe: An ontological interpretation of quantum theory, with B.J. Hiley, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-12185-X (final work)

- 1996. On Dialogue. editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge, hardcover: ISBN 0-415-14911-8, paperback: ISBN 0-415-14912-6, 2004 edition: ISBN 0-415-33641-4

- 1998. On Creativity, editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge, hardcover: ISBN 0-415-17395-7, paperback: ISBN 0-415-17396-5, 2004 edition: ISBN 0-415-33640-6

- 1999. Limits of Thought: Discussions, with Jiddu Krishnamurti, London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-19398-2.

- 1999. Bohm–Biederman Correspondence: Creativity and Science, with Charles Biederman. editor Paavo Pylkkänen. ISBN 0-415-16225-4.

- 2002. The Essential David Bohm. editor Lee Nichol. London: Routledge, ISBN 0-415-26174-0. preface by the Dalai Lama

- 2017. David Bohm: Causality and Chance, Letters to Three Women, editor Chris Talbot. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-319-55491-4.

- 2018. The Unity of Everything: A Conversation with David Bohm, with Nish Dubashia. Hamburg, Germany: Tredition, ISBN 978-3-7439-9299-3.

- 2020. David Bohm’s Critique of Modern Physics, Letters to Jeffrey Bub, 1966-1969, Foreword by Jeffrey Bub, editor Chris Talbot. Cham, Switzerland: Springer. ISBN 978-3-030-45536-1.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Jump up to:a b B. J. Hiley (1997). "David Joseph Bohm. 20 December 1917 – 27 October 1992: Elected F.R.S. 1990". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 43: 107–131. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1997.0007. S2CID 70366771.

- ^ Peat 1997, pp. 316-317

- ^ Jump up to:a b David Bohm: Wholeness and the Implicate Order, Routledge, 1980 (ISBN 0-203-99515-5).

- ^ Jump up to:a b Comparison between Karl Pribram's "Holographic Brain Theory" and more conventional models of neuronal computation

- ^ Wholeness and the Implicate Order, Bohm - 4 July 2002

- ^ David Bohm: On Dialogue (2004) Routledge

- ^ Becker, Adam (2018). What is Real?: The Unfinished Quest for the Meaning of Quantum Physics. Basic Books. p. 115. ISBN 978-0-465-09605-3.

- ^ Freire Junior, Olival (2019). David Bohm:A Life Dedicated to Understanding the Quantum World. Springer. p. 37. ISBN 978-3-030-22714-2.

- ^ [1] - By the Numbers – David Bohm

- ^ Peat 1997, p.21. "If he identified Jewish lore and customs with his father, then this was a way he would distance himself from Samuel. By the time he reached his late teens, he had become firmly agnostic."

- ^ Garber, Marjorie; Walkowitz, Rebecca (1995). Secret Agents: The Rosenberg Case, McCarthyism and Fifties America. New York: Routledge. pp. 130–131. ISBN 9781135206949.

- ^ Peat 1997, p.64

- ^ Russell Olwell: Physics and Politics in Cold War America: The Two Exiles of David Bohm, Working Paper Number 20. Program in Science, Technology, and Society. Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

- ^ Kumar, Manjit (24 May 2010). Quantum: Einstein, Bohr, and the Great Debate about the Nature of Reality. ISBN 9780393080094.

- ^ Albert Einstein to Patrick Blackett, 17 April 1951 (Albert Einstein archives). Cited after Olival Freire, Jr.: Science and Exile: David Bohm, the cold war, and a new interpretation of quantum mechanics, HSPS, vol. 36, Part 1, pp. 1–34, ISSN 0890-9997, 2005, see footnote 8. Archived 26 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Observing the Average Trajectories of Single Photons in a Two-Slit Interferometer.

- ^ D. Bohm: The characteristics of electrical discharges in magnetic fields, in: A. Guthrie, R. K. Wakerling (eds.), McGraw–Hill, 1949.

- ^ Maurice A. de Gosson, Basil J. Hiley: Zeno paradox for Bohmian trajectories: the unfolding of the metatron, 3 January 2011 (PDF – retrieved 16 February 2012).

- ^ B. J. Hiley: Some remarks on the evolution of Bohm's proposals for an alternative to quantum mechanics, 30 January 2010.

- ^ David Bohm, Basil Hiley: The Undivided Universe: An Ontological Interpretation of Quantum Theory, edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-library 2009 (first edition Routledge, 1993), ISBN 0-203-98038-7, p. 2.

- ^ Russell Olwell: Physics and politics in cold war America: the two exiles of David Bohm, Working Paper Number 2, Working Program in Science, Technology, and Society; Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- ^ Jump up to:a b Olival Freire, Jr.: Science and Exile: David Bohm, the cold war, and a new interpretation of quantum mechanics Archived 26 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine, HSPS, vol. 36, Part 1, pp. 1–34, ISSN 0890-9997, 2005

- ^ "Erwin Madelung 1881–1972". Goethe-Universität Frankfurt am Main. 12 December 2008. Archived from the original on 12 February 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2012.

- ^ Pines, D; Bohm, D. A (1951). "Collective Description of Electron Interactions. I. Magnetic Interactions". Physical Review. 82 (5): 625–634. Bibcode:1951PhRv...82..625B. doi:10.1103/physrev.82.625.

- ^ Pines, D; Bohm, D. A (1952). "Collective Description of Electron Interactions: II. Collective vs Individual Particle Aspects of the Interactions". Physical Review. 85 (2): 338–353. Bibcode:1952PhRv...85..338P. doi:10.1103/physrev.85.338.

- ^ Pines, D; Bohm, D. (1953). "A Collective Description of Electron Interactions: III. Coulomb Interactions in a Degenerate Electron Gas". Physical Review. 92 (3): 609–626. Bibcode:1953PhRv...92..609B. doi:10.1103/physrev.92.609.

- ^ Bohm, D.; Aharonov, Y. (15 November 1957). "Discussion of Experimental Proof for the Paradox of Einstein, Rosen, and Podolsky". Physical Review. American Physical Society (APS). 108 (4): 1070–1076. Bibcode:1957PhRv..108.1070B. doi:10.1103/physrev.108.1070. ISSN 0031-899X.

- ^ Bell, J.S. (1964). "On the Einstein Podolsky Rosen paradox" (PDF). Physics Physique Fizika. 1 (3): 195–200. doi:10.1103/PhysicsPhysiqueFizika.1.195.

- ^ "collected papers". Archived from the original on 11 February 2006. Retrieved 26 November 2005.

- ^ Bohm, David; Hiley, Basil J.; Stuart, Allan E. G. (1970). "On a new mode of description in physics". International Journal of Theoretical Physics. Springer Science and Business Media LLC. 3 (3): 171–183. Bibcode:1970IJTP....3..171B. doi:10.1007/bf00671000. ISSN 0020-7748. S2CID 121080682.

- ^ David Bohm, F. David Peat: Science, Order, and Creativity, 1987

- ^ Basil J. Hiley: Process and the Implicate Order: their relevance to Quantum Theory and Mind. (PDF Archived 26 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine)

- ^ The holographic brain Archived 18 May 2006 at the Wayback Machine, with Karl Pribram

- ^ Mary Lutyens (1983). "Freedom is Not Choice". Krishnamurti: The Years of Fulfillment. Krishnamurti Foundation Trust Ltd. p. 208. ISBN 978-0-900506-20-8.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e David Edmund Moody (2016). An Uncommon Collaboration: David Bohm and J. Krishnamurti. Alpha Centauri Press. ISBN 978-0692854273.

- ^ J. Krishnamurti (2000). Truth and Actuality. Krishnamurti Foundation Trust Ltd. ISBN 978-8187326182.

- ^ J. Krishnamurti and D. Bohm (1985). The Ending of Time. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0060647964.

- ^ J. Krishnamurti and D. Bohm (1999). The Limits of Thought: Discussions between J. Krishnamurti and David Bohm. Routledge. ISBN 978-0415193986.

- ^ Peat 1997

- ^ Jump up to:a b Gardner, Martin (July 2000). "David Bohm and Jiddo Krishnamurti". Skeptical Inquirer. Archived from the original on 9 March 2015.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d David Bohm (1994). Thought as a System. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0415110303.

- ^ David Bohm (12 October 2012). On Creativity. Routledge. p. 118. ISBN 978-1-136-76818-7.

- ^ David Bohm; F. David Peat (25 February 2014). Science, Order and Creativity Second Edition. Routledge. pp. 204–. ISBN 978-1-317-83546-2.

- ^ Peat 1997, p.80

- ^ Hiley, Basil; Peat, F. David, eds. (2012). Quantum Implications: Essays in Honour of David Bohm. Routledge. p. 443. ISBN 9781134914173.

- ^ Peat 1997, pp.308–317

- ^ Peat 1997, pp. 308–317

- ^ Infinite potential: the life and times of David Bohm (film) www.infinitepotential.com, accessed 28 December 2020

- ^ Kožnjak, Boris (2017). "The missing history of Bohm's hidden variables theory: the Ninth Symposium of the Colston Research Society, Bristol, 1957". Studies in History and Philosophy of Science Part B: Studies in History and Philosophy of Modern Physics. 62: 85–97. Bibcode:2018SHPMP..62...85K. doi:10.1016/j.shpsb.2017.06.003.

Sources[edit]

- David Z. Albert (May 1994). "Bohm's Alternative to Quantum Mechanics". Scientific American. 270 (5): 58. Bibcode:1994SciAm.270e..58A. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0594-58.

- Joye, S.R. (2017). The Little Book of Consciousness: Pribram's Holonomic Brain Theory and Bohm's Implicate Order. The Viola Institute. ISBN 978-0-9988785-4-6.

- Greeg Herken (2002). Brotherhood of the Bomb: The Tangled Lives and Loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller. Holt. ISBN 0-8050-6589-X. (information on Bohm's work at Berkeley and his dealings with HUAC)

- F. David Peat (1997). Infinite Potential: the Life and Times of David Bohm. Addison Wesley. ISBN 0-201-40635-7.https://archive.org/details/infinitepotentia0000peat

- B.J. Hiley, F. David Peat, ed. (1987). Quantum Implications: Essays in Honour of David Bohm. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-06960-2.

- David Bohm, Sarah Bohm (1992). Thought as a System. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-11980-4. (transcript of seminar held in Ojai, California, from 30 November to 2 December 1990)

- Peter R. Holland (2000). The Quantum Theory of Motion: an account of the de Broglie-Bohm Causal Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-48543-6.

Further reading[edit]

- William Keepin: A life of dialogue between science and spirit – David Bohm. In World Scriptures: Leland P. Stewart (ed.): Guidelines for a Unity-and-Diversity Global Civilization, World Scriptures Vol. 2, AuthorHouse. (2009) ISBN 978-1-4389-8086-7, pp. 5–13

- William Keepin: Lifework of David Bohm. River of Truth, Re-vision, vol. 16, no. 1, 1993, p. 32 (online at scribd)

External links[edit]

- The David Bohm Society

- The Bohm Krishnamurti Project: Exploring the Legacy of the David Bohm and Jiddu Krishnamurti Relationship

- David Bohm's ideas about Dialogue

- the David_Bohm_Hub. Includes compilations of David Bohm's life and work in form of texts, audio, video, and pictures

- Lifework of David Bohm: River of Truth: Article by Will Keepin (PDF-version)

- Interview with David Bohm provided and conducted by F. David Peat along with John Briggs, first issued in Omni magazine, January 1987

- Archive of papers at Birkbeck College relating to David Bohm and David Bohm at the National Archives

- David Bohm at the Mathematics Genealogy Project

- 1979 Audio Interview with David Bohm by Martin Sherwin at Voices of the Manhattan Project

- The Bohm Documentary by David Peat and Paul Howard (in production)

- The Best David Bohm Interview about "The Nature of Things" by David Suzuki 26 May 1979

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 8 May 1981, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - interview conducted by Lillian Hoddeson in Edgware, London, England

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 6 June 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session I, interviews conducted by Maurice Wilkins

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 12 June 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session II

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 7 July 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session III

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 25 September 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session IV

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 3 October 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session V

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 22 December 1986, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session VI

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 30 January 1987, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session VII

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 7 February 1987, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session VIII

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 27 February 1987, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session IX

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 6 March 1987, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session X

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 3 April 1987, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session XI

- Oral History interview transcript with David Bohm on 16 April 1987, American Institute of Physics, Niels Bohr Library and Archives - Session XII