Ch 15 Quakers and Non-theism

by Dan Christy Randazzo

in The Cambridge Companion to Quakerism (2018)

---

1] Introduction

Non-theism is a minority tradition within the worldwide Religious Society of Friends (RSOF), with the vast majority of self-defined non-theist Friends hailing from either Britain or the United States. The term 'non‑theism can best be understood as a compromise term, for it encompasses a very wide theological and conceptual tent, the members of which hold a dizzying array of positions on the existence of God, how 'God can be defined or understood, the main components of Quaker identity, and what level of priority to give each of those components for the construction of 'Quakerness.

Nothing unites all non-theists except a sense that they do not view the construct of 'God' as a personal, monotheist deity. Non-theism is knowingly constructed as an undefined definition in an effort to be as inclusive as possible for all people who seek to claim a Quaker identity, yet who cannot ascribe to any form of personal monotheism. Many non-theist Friends use the label as shorthand for explaining their view of Quakerism, yet do so reluctantly, recognising that while there are non-theists in the RSOF, those non-theists often hold very different views from one another.

Non-theism is, at its core, a product of Liberal Quakerism, present throughout the world, wherever Liberal Quakerism exists. Non-theistic thought in Liberal Quakerism most often reflects the context of Britain Yearly Meeting, and the Friends General Conference in the United States, however, as the majority of non-theist writers are either British or North American.

The existence of non-theism within Liberal Quakerism is connected to the increased diversity of belief within Liberal Quakerism in the latter half of the twentieth century. At the beginning of the century, Liberal Quakers were generally Christocentric. Over time, and particularly by the middle of the century, Universalist theology took hold within Liberal Quakerism. This was met with significant critique at first; yet soon Universalism claimed space within Liberal Quakerism alongside Christocentrism. Eventually, Christocentrism was marginalised, as Liberal Quakerism became largely Universalist. This trend towards questioning the core assumptions of Liberal Quakerism has not been completed, and the current tension lies over the question of God.

This development is reflected in the development of Universalist groups in both Britain and the United States. As these groups developed and gained acceptance within Liberal Quakerism, non-theism embedded itself within the groups, as the only available outlet for non-theists to develop community within the RSOF.

The groups provided a home for non-theists and aided in the development of both community and of non-theist thought. The relationships between non-theists and other Universalists were not always easy, however, due to the diversity inherent in Universalist Quaker theology.

Yet, Universalist Friends were generally welcoming to non-theist members as well as giving space in their journals to the expression of non-theist voices. Thus, as Universalism developed as a distinct tradition within Liberal Quakerism, non-theism was also given space to develop.

Non-theism is therefore a tradition whose perspectives on the Religious Society of Friends, theological concerns and understanding of the fundamental priorities of Quakerism are coloured by Liberal Quaker theology and practice and have been shaped by the attempt to find a place in a religious tradition which places the presence of God within each person as its most fundamental theological claim.

Non‑theist writing reflects these concerns, with a determined focus on demonstrating that the roots of non‑theism go deep within Quaker history and theology. This effort seeks to not only demonstrate that the theological openness of Liberal Quakerism allows space for non-theist theological interpretations, but that Liberal Quakerism should be mainly focused on practice and ethical concerns. Success in this endeavour would render differences on the existence or non-existence of God less meaningful for Quaker identity, leading to a new form of Quakerism which places the question of God as an interesting side aspect for a religious faith focused entirely on the present, lived reality.

This chapter sketches out these themes by focusing on non-theist perspectives, including non-theist publications as well as non-theist writings within Universalist publications. This chapter includes a discussion on ways which non-theists have chosen to define themselves; interpretations of Quaker history and identity; assessments of the priority of reason and Quaker practice as core aspects of both theist and non-theist Quakerism; and a potential outline for a unique a/theology for non-theism, including avenues where non-theist Friends have demonstrated efforts to bridge the theist/non-theist divide, and potential areas of future development in non-theist thought.

2] Definitions of Non-theism

Most Quaker non-theists tend to view 'God' as a human construct. They see Quakerism as a way of life shaped by the Testimonies, Quaker worship and business practice. Non-theists define religion as the means of placing these aspects of Quaker life within a certain community of meaning. The perspective of Quaker non-theism toward theistic belief can be placed on a spectrum of perspective from:

- a dangerous superstition,

- through a relatively harmless (if outmoded) silliness and

- finally towards a legitimate and potentially powerful way of understanding human existence.

David Boulton, a noted non-theist Quaker, has made multiple attempts at establishing a common definition. He defines non-theism as 'the absence of belief in deity/ies, in the existence of God (where "existence" is understood in the realist, objective sense), especially belief in one supreme divine Creator' (Boulton 2006, 6). Boulton describes the development of the term as a process of accepting the 'least disliked option', where other terms, such as 'atheist', 'humanist' and 'naturalist' were all deemed either too controversial or as carrying unnecessary negative stigma, thus being ineffective umbrella terms for an option which Boulton sees as rejecting the theistic concept of 'God' (2006, 7). Boulton emphasises rejection in part because he does not view theistic constructions of God as real, instead proclaiming that God is a human construct, serving human needs. He proclaims that he has deep respect for the concept of 'God', in that within all expressions of 'God' are the symbolic and poetic metaphors which signify 'the sum of our human values, the imagined embodiment of our human ideals, the focus of our ultimate concern'. God is 'no more, but, gloriously, no less, than all that makes up the human spirit' (Boulton 2006, 8). However, he also stresses the need to reject theistic conceptions of God because he sees belief in such conceptions to be dangerous, leading to such harmful human behaviours as religiously based violence, exclusion, and intolerance (Boulton 2006, 9-10).

In this, he is in line with John Linton, the non-theist Universalist who established the Quaker Universalist Group (QUG) in Britain. In an early edition of The Universalist, the main journal for the QUG, Linton suggested that he was much better off for having given up his 'delusions' about the existence of God, along with his faith (1984,17). He then claimed that religious faith often causes more violence than what he termed 'reason', thus demonstrating the necessity for the RSOF, in particular, to give up all divisions based on religious faith. For Linton, this stemmed both from an aversion to Christian truth claims as well as a strong agnostic stance towards the question of 'Truth'. Thus, the openness and willingness to listen to all religious perspectives of Quaker Universalism appealed to him and inspired him to aid in the growth of Quaker Universalism. Yet, he viewed this pursuit as more than just an effort at greater inclusion within Liberal Quakerism as it existed. Instead, he sought to have Quakerism not only welcome agnostics especially, due to what Linton viewed as similar underlying attitudes and ethical viewpoints, but also as part of an overall turn in Quakerism towards ethical Universalism and specifically away from Christianity (Linton 1994, 74).

Linton would therefore define Quaker non-theism as not only

- intellectually open and

- focused on ethics but also

- explicitly agnostic, Universalist and

- highly critical of Christianity.

Notably, Linton desired that this change would occur as a natural evolution of the Society; Linton claimed, in terms of Universalists specifically, that 'QUG members don't seek a schism within Quakerism, nor to "twist the Society" to its view' (1979, 1).

Not all non-theists ascribe to this evangelistic impulse. Bowen Alpern, a self-described atheist Friend, views the theist/non-theist divide in Quakerism as by far the least important divide amongst Friends. In fact, he claims that the division caused by this divide is actually a distraction from the Quaker effort to help create the peaceable kingdom, which is so vitally important that the RSOF must quickly adapt so that it can become whole, growing as a community in such a way that it can transcend its divisions, all at a much more rapid pace than Quakers might be comfortable with (B. Alpern 2006,83-84). This reflects his core view that Quakerism is a way of life based on the ethics of peacemaking, which needs to adopt an 'all hands on deck' approach. He thus views theological diversity as a positive thing, as long as that diversity is rooted in the common purpose of the Quaker life. This reflects a common trend amongst non-theist Friends to define religion as those structures and practices which serve to connect people together in community. Robin Alpern suggests this definition of religion as the most appropriate, as the religious life both derives meaning and structure from, and provides the same to, a community of like-minded people seeking to live by a certain set of principles (R. Alpern 2006, 19).

A corollary to Bowen Alpern's vision of a theologically diverse and ethically unified Quakerism would be an emphasis on- the Quaker rejection of creeds, and

- a resulting openness towards theological diversity and

- insistence on privacy about individual belief,

This does not mean that theological belief is immaterial to non-theist Friends, however. A significant thread in non-theist discourse is the need to allow the contours of religious belief to be 'left up to mystery', as Hubert J. Morel-Seytoux argues (2006, 129). This emphasis on mystery runs counter to Boulton's stated certainty about the non-existence of God beyond a human construct, for mystery implies that there are, at least, areas of deliberate uncertainty in the minds of some non-theists regarding the concept of 'God'.

The end of the chapter revisits this question as it plots out a future for non-theists.

3] Non-theist Historiography

Non-theism emerged as a definable aspect of Quakerism with the rise of Universalism within Liberal Quakerism in the early twentieth century, yet non-theists claim a long heritage of religious scepticism, dating back to the mid-seventeenth century. Os Cresson, a Quaker naturalist, devoted a significant

portion of his recent work Quaker and Naturalist Too to exploring what he terms the 'roots' (historical development of scepticism as a key aspect of Quaker thought) and 'flowers' (the resulting development of Quaker non-theism as a community and a school of thought) of Quaker non-theism. While Cresson acknowledges that the vast majority of people listed as 'roots' of non-theism likely held strongly theistic beliefs, the thinkers who he claims laid the foundation for Quaker scepticism held beliefs that aided in the expansion of the boundaries for Quaker identity and thus 'helped make Friends more inclusive' (2014, 65).

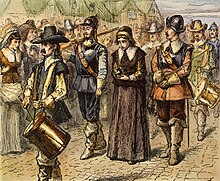

By expanding the bounds of Quaker non-theist history beyond explicitly non-theist thinkers, Cresson allows non-theists to lay claim to a significant portion of the Quaker heritage that might otherwise be reserved exclusively for theist Quakers. This kind of creative re-appropriation reflects many aspects of the creation of non-theist identity, in that non-theist Quakers are often forced to develop their own understanding of what it means to be Quaker in a tradition which places significant value on its earliest thinkers, all of whom were undeniably theist. Reflecting this, Boulton has made an attempt to suggest that George Fox's vision of God was 'more inner light than outer superman', a perspective which Boulton claims was denounced as 'atheism' by 'religious traditionalists' (2012, 2). When, and in what manner, these traditionalists made these statements is not expanded upon, however. Similarly, both Boulton and Cresson lay claim to other notable Friends and friends of Friends, with Gerrard Winstanley, the Diggers, the Manchester Free Friends, Lucretia Mott and Henry Cadbury mentioned most often in their writings.

These efforts have endured some critique from other Quakers who view some of these theories to be, at best, historically inaccurate. Representative of this trend, and referring to efforts to locate the modern Liberal Quaker willingness to 'seek' without a specific intent to find a particular vision of God, Patrick Nugent claims that just would not make sense in the past: the early Seekers wanted to find something specific, related to the conversion moment which occurred when the Seeker found and had a definitive transformation due to a 'definitive intervention by Jesus Christ' (2012, 53). Similarly, Nugent claims that non-theist efforts to locate even a proto-non-theism in George Fox's thought are incorrect. Nugent claims that Fox simply cannot be accused of atheism in the way that Boulton suggests. The same applies to Lucretia Mott: Nugent notes that non-theist attempts to locate within Mott's defence of Universalist belief a proto-non-theism does not take into account Mott's continued insistence, throughout her life, on the existence of God. Finally, Nugent argues that 'a thorough read of the first 150 years of Quaker history cannot sustain non-theism as authentically Quaker', meaning that non-theism cannot be rooted in early Quaker thought, and instead must be seen as a much more recent development (2012,5 1). This does not

imply that Nugent fails to see value in non-theism; in fact, he claims that there is much theological potential with non-theism.

This also reflected the views of Kingdon Swayne (1920-2009), who was an influential non-theist Quaker Universalist and a member of the Quaker Universalist Fellowship (QUF), the main Quaker Universalist group in the United States. Swayne claimed that while he did not 'mean to cut us off from our roots', that the intense focus on locating Universalist beliefs (which he includes himself in), and thus gaining legitimacy from, the views of early Friends is unhelpful (1986, 10). This is due to what Swayne terms the 'enormous intellectual gulf standing between late twentieth-century Friends and the mid-seventeenth century. Not only has the modern world been shaped by intervening centuries of religious thought, Swayne argues, it would also be far too difficult to effectively, and accurately, translate complex religious concepts and language across that same divide. Modern Friends should therefore avoid adopting an 'idolatrous' attitude towards the early Friends and instead focus their efforts on building a modern Quakerism from modern thought.

Following Swayne's guidance, focusing on the development of non-theist thought in the twentieth century reveals a fascinating heritage. Non-theists have identified certain Quakers as either influential on later non-theism or whose own non-theist writing contributed to the development of non-theist thought. Most prominent amongst these was Henry Cadbury (Boulton and Cresson 2006, 98). While Cadbury was quiet about his scepticism of theistic belief during his career, he would give his classes a copy of a paper he had written defending non-supernatural experience within Quakerism. Cadbury took pains to fully acknowledge that many, even a majority of Quakers can have experiences of a supernatural God. Yet, he admitted that he had rarely, if ever, had such an experience. Instead, he developed what he understood to be his own way of being Quaker, based on Quaker values, leading to a 'way of life' (Cadbury 2000, 30).

The first non-theist organisation which sought to align itself with Quakerism was the Humanist Society of Friends (HSOF), begun by Lowell Coate, in 1939. The HSOF was not explicitly Quaker, yet it included numerous Friends amongst its members and intentionally strove to align itself with Liberal Quaker values. Strong emphasis was placed on humanism as the core philosophy for the group, with a concomitant emphasis on peace, reflecting the strong influence of the Quaker members. The HSOF offered a vision of religious humanism which was 'scientific' and 'intensely focused' on the current situation of people's lives. As leader, and editor of the HSOF newsletter The Humanist Friend, Coate offered

a definition for religion as devotion to a principle, an ideal, without belief in dogmas. Coate emphasised the necessity of having a list of 'superior and ideal human characteristics' which manifested themselves in work for social change (1939, 1). Demonstrating the seriousness with which HSOF held its Quaker connection, The Humanist Friend would reprint letters from notable Friends on issues of concern. Representative of this trend is a letter from Rufus Jones on the humanitarian crisis presented by the Second World War, and the challenge for Friends to focus not on abstract ideologies but on the practical changes that Friends could make to the lives of people affected by war (Jones 1939, 7). Notably, the HSOF sought to maintain its connection with Friends over the next seventy years. It was not until 2003 that the HSOF board decided to remove 'Of Friends' from its title, due to a desire to demonstrate how its mission had gradually evolved into serving the wider humanist community (http://thehumanistsociety.org/about/history!).

The most prominent discussions of non-theism, until at least 1976, were mainly critical of non-the‑ism.

- The Faith of An Ex-Agnos‑tic, number 46, and Alexander C. Purdy's 1967 pamphlet,

- The Reality of God: Thoughts on the 'Death of God' Controversy, number 154), and

- one Swarthmore Lecture (William Homan Thorpe's 1968 lecture, Quakers and Humanists).

John MacMurray's 1965 lecture, Search for Reality in Religion, as it sought to apply a rationalist philosophy perspective on Quakerism, which MacMurray noted was a generally experiential religion; and Richard S. Peters's 1972 lecture, Reason, Morality and Religion, as it demonstrated that reason could be utilised to develop a religion focused on structuring the present life around reasonable moral values.

By the late 1970s, Universalism was beginning to receive a greater level of acceptance amongst Liberal Friends, with non-theists at the forefront of the development of both the QUG and the QUF. Corresponding with this trend was Janet Scott's 1980 lecture What Canst Thou Say? Towards a Quaker Theology, noted as the first time that Christianity was decentred as the sole focus of Liberal Quaker theology (Davie 1997, 218). These movements, in tandem, emboldened Universalists, and by extension, non-theists, to reimagine Quaker theological possibilities.

The first official recognition and effort to serve the needs of non-theist Friends occurred with the first non-theist workshop, entitled 'Nontheistic Friends', held at Friends General Conference (FGC) Annual Gathering in 1976 (Boulton 2012, 35). No any other official RSOF acknowledgement of non-theism occurred until the 1996 FGC Annual Gathering, when one workshop, entitled 'Nontheism Amongst Friends', was held.

4] Non-theist Interpretation of Quaker Identity

There is no one unifying interpretation of Quaker identity, and expression of the importance of that identity amongst non-theists, beyond the fact that they all feel as if they are Quaker. Some non-theist Friends state it as a plain correlation: their values align with what those of the RSOF; they feel at home amongst Quakers; and Quaker worship gives them a sense of connection, community and meaning. As these are the most important markers of Quaker identity for these Friends, they believe these markers are sufficient. They are Quaker by dint of the fact that they 'feel' like a Quaker (Filiacci 2006, 117). An unspoken aspect of this approach is that they are not troubled by the existence and testimony of theist Friends in meeting. Other non-theist Friends feel more compelled to insist on proclaiming either the value of non-theist perspectives or the challenges they encounter with theistic belief.

Marian Kaplan Shapiro is representative of this perspective. Shapiro claims that she views Jesus as an effective moral teacher yet is deeply uncomfortable with any language which expresses the value of following Jesus as 'Christ', 'Lord' or any other honorific related to his status as 'messiah' or as supernatural deity. This extends to testimony in meeting to that effect, to which she feels compelled to respond by 'speaking her truth' about its inherent dangers (Shapiro 2006, 132). Despite this, Shapiro has experienced two seemingly paradoxical realities: not only has she consistently been treated well and welcomed by theists in meeting, she also has been forced to acknowledge that she is envious of the security that theism seems to provide believers. Shapiro has chosen to simply allow this paradox to exist, proclaiming simply that 'I am a Friend' (2006, 132).

Many non-theist Friends have not experienced such an untroubled welcome as non-theists, however.

For Robin and Bowen Alpern, this is related to a negative experience of being asked to leave their meeting after proclaiming their non-theism publicly (R. Alpern 2006, 24). Yet, for others their trouble resides with the seeming paradox at the heart of Quaker non-theism: how can a person who does not ascribe to a belief

in God or deity/ies be a full member of a religious society which holds as its central theological tenet that all people can experience a direct and transforming experience of God? As with all aspects of Quaker non‑theism, there is a vast diversity of ways non-theists have approached this problem.

Kingdon Swayne approaches it by laying out what he views as the five concepts which can be utilised in an effort to unite all Liberal Quakers:

- responsiveness to a religious impulse and a desire to engage in religious community;

- personal freedom following a religious impulse;

- acceptance of meeting for worship as a core element of Quaker spirituality;

- tolerance for diversity of religious metaphorical language; and,

- finally, having 'one's life speak' in an active way (Swayne 1987, 10).

an insistence on tolerance for theological diversity. In this way, Swayne can reverse the direction of critical inquiry back towards theists and claim that theist Friends must follow the same rules as non-theist Friends.

Robin Alpern provided an effective demonstration of taking this tactic - reversing the critical mirror - to react to the most common response to her claiming a non-theist identity, 'Why Not Join the Unitarians? This question is presented as both a straightforward query as well as a dismissive suggestion about the supposed blasé attitude which Unitarians are assumed to take towards theological content, a stance which the imaginary interlocutor appears to claim Alpern holds as well. This challenge is often presented as a theist critique of non-theism: if you desire to remain Quaker, you must present an argument which effectively deals with the centredness of theist belief in Liberal Quaker theology.

She views talk about God as inherently empty, as such talk does not specifically lead to the direct act of making a better world.

Thus she demonstrates her command of Swayne's technique of using some Quaker essentials to critique other essentials. She argues that as she was taught that communal discernment is essential, that her development of these beliefs while engaged in communal discernment leads to the inescapable conclusion that they must, in fact, be 'true', at least in some sense. She claims that as all humans desire companionship and community, her unwillingness to speak the language of God in worship does not nec essarily mean that she and by extension all atheists and agnostics are not able to understand truly being 'gathered in worship. She then attacks the core aspect of that assumption by stating that rejecting her religious potential is to deny her humanity.

She completes the reversal of the critical mirror by claims that the true 'parasites (an epithet that she claims has been directed her way previously) are not non-theists who gain a sense of the religious by being members of Quakers but are instead those theists whose belief in God only exists because they are amongst company who believe. By not contributing their doubts about God to the community, she suggests that theists want to feed off the good feelings of general agreement, thus avoiding the discomfort of controversy. Finally, she claims that when one states a final belief that he or she has arrived at through seeking, one stops seeking and thus the belief causes that person to become ossified.

In this, Alpern argues that taking continuing revelation to its logical conclusion demands that Quakers should never settle on a final belief, especially belief in 'God. The obvious response is whether this includes the lack of belief in a deity, however. While Alpern does demonstrate how reversing the critical mirror and engaging with core Liberal Quaker concepts can create new theological possibilities, and also develop non-theist expressions of Quaker identity, her methodological approach rests on a potentially challenging core assumption: that everyone has doubts about the existence of God. Quaker theists firmly claiming a faith in Gods existence, unmarked by doubt, might prove challenging to her methodology.

5] The A/Theology of Non-theism

This chapter has provided examples of non-theist theological engagement, including constructions of who, or what, the concept of 'God' might mean to individual non-theist Friends. Effectively, if any theological language can be imagined that is not belief in God, a personal, interventionist monotheist supernatural non-theism has the potential of engaging with it.

This does not leave non-theist theology at an impasse, forever forced to listen to new and different visions of an individual's experience, or lack of experience, with 'God', and failing to develop any cohesive critical language to bring to bear. Quaker philosopher Jeffrey Dudiak offers a potential way forward by continuing the method established in this chapter of reversing the question at hand: whether, in fact, theism and a/theism are binary. He begins his engagement by unsettling the modern assumption of a binary by reframing the question in terms of pre-modern religious language. He claims that atheism and theism, in their modern forms, are only possible in a secular, modern world where faith ('surrendered immersion in a world of ineluctable meanings', as he defines it) has lost meaning (Dudiak ZUIz, 26).

The possibility that one can either 'possess' belief or unbelief, and that this is first a vitally important question, or even an option to humans, arose in a modern, secular age (Dudiak 2012, 26). Faith is now de‑pendent on both belief and unbelief. Dudiak admits that the age of reason did offer liberation from often crushing religious structures, yet he insists that some things have been lost in this transition.

- First amongst these is a change in the focus of subjectivity.

- In the pre-modern religious imaginary, to be a subject was to be 'subject to', a passive being upon whom forces acted which were transcendent.

- Now, subject is the external 'subject of, an object to be perceived or acted upon.

- What 'exists' is no longer lived as gift but is dependent upon the judgement of thought and reason, which in turn gauges its existence/non-existence as well as its value.

- Dudiak claims that this is a shift from a medieval focus on ontology to a modernist focus on epistemology; recast, this is the shift from faith to belief, as belief is inherently a question of assent to a statement of fact.

- The emphasis is also no longer on the place which the knower has within the world, but what the meaning of world is over against the knower.

- A result of this shift is that belief in God is prerequisite for finding selves in God's world.

- A corollary to this is a shift from faith as trusting immersion in a world which gives meaning, as context for belief, to belief (and thus knowledge and assent) as prerequisite for faith.

- Thus, it is now foolish to have faith in God without belief. The result of this shift is the creation of a/theism, which places the highest priority on reason and the ability to answer to reason, for a focus on belief implies a focus on knowledge, which in turn necessitates reason.

Dudiak suggests that modernity therefore places the 'knowing subject-known object' as foundational, and limits ways of understanding God (2012, 30).

- A denial of supernatural reduces God to a human projection in the form of a metaphor or story (immanent naturalism), whereas limiting God to a supernatural object means transcendent theism is the only way to imagine a theistic God.

- This supernatural transcendent creates theistic claims that are literally in-credible, in that they are non-credible and irrational, and thus impossible to believe.

- The end result is that both sides wind up failing to have a vision of God worth spending any time or attention dealing with.

- Dudiak argues that the most productive way forward would be to dismiss the modern binary as foundational to any God-talk or relationship.

- Instead, Quakers should decentre human emphasis on 'seeing', or understanding (judging the credibility of objective facts), and commit to being called by 'hearing' the voice of God.

Shannon Craigo-Snell suggests that Quakerism already possesses a number of elements which bridge the division between modern and pre-modern concerns, which could provide the kind of bridging theology/atheology which non-theists argue is essential for the future of a Liberal Quakerism with non-theism as an integral component (2012, 49).

- experience and reasoning (pre-modern and modern ways of engaging with one's place in the world) are both already present in Quaker worship,

- a reluctance to separate private from public (thus, 'having one's life speak) and the corollary insistence that religion extends to every sphere of personal and communal life.

- I would argue that a final component that brings these aspects together is a rejection of the personal/communal binary, relating to the Light: as the Light Within is available to each individual person, it is thus also available to the entire community, binding together the community in an interdependent web.

Resonances of this exist within the narratives of non-theist a/theology, even in those narratives which seem most antithetical to a theistic perspective. The two themes which present the most potential for interlocking with this effort include 'God as cosmos and 'God as human values.

Non-theist visions of the cosmos are varied, yet generally encompass the entirety of what is known to exist in the physical universe.

This force is still entirely physical, and a manifestation of the physical world, yet is still awe-inspiring (Lawrence 2006, 119).

Gudron Moller (a Quaker from Aotearo a/New Zealand Yearly Meeting) references the interconnection amongst all beings yet adds an emphasis on human evolution.

Finally, George Amoss Jr. has taken as his theological project the development of ways of repurposing traditional Quaker language, including Christian language, in ways that bridge the seeming gap between non-theism and theism, in an effort to honour the experience of theists while also honouring his own.

Reflecting this, Amoss references the construct of the Light in a way that is suggestive of interdependent presence. Amoss stresses that the Light is not a possession, or something to believe in (reflecting Dudiaks concerns) but is instead an experience to reside within. Residing in this Light will result in transformation for both our personal lives as well as our communal lives. We are then capable of leading to a way of life demonstrative of this same Light within (Amoss 19891 21-24).

Amoss has developed this theme in significant detail since 1989, cataloguing his work on his website, Postmodern Quaker. Amoss has applied his method to his most recent project, Quaker Faith and Practice for the 21 st Century. This document retains traditional Quaker Christological language, while interpreting that language through the lens of both Liberal Quaker theology and Amosss vision of non-theism within Liberal Quakerism. Amoss expressly seeks to develop a methodology which respects and reflects the experience of both theism and non-theism (2016). He develops a construct of the Light as an experience to reside within, which will result in both individual and communal transformation. He utilises Christian language to describe the experience of Light, and the manner of the resulting transformation, without actually claiming any 'Christological' meaning.

Roland Warren suggests a way to bridge both the vision of 'God' as cosmos as well as 'God' as human value. Warren suggests that God is something 'created' by humans to explain the relation between humans and their experience of objective circumstances (2002, 6). God is what we create to explain the relationships that we experience between ourselves, our world, and the transcendent ideals that we hew to. God is therefore a product of the human mind, but not only so, in that God does not exist for humans outside of human perception. In other words, God is a framework applied to a set of experiences, circumstances and objective realities to make sense of our world, as well as the inexplicable. At its core, this is the 'religious experience'. Warren claims that while everyone has the potential for a religious experience, not everyone develops the hermeneutic for framing and understanding the experience in relation to a 'God'.

In this sense, he reflects the concerns of Boulton, Linton and other non-theists who stress that 'God' is purely a human construct.

Warren offers something new, however, when he suggests that the root of sentience and conscious‑ness cannot be found within the physical world. Instead, it seems to lie in another plane of existence, while of course being very present in the physical world, and rooted to it: when the physical body is dead, consciousness goes away. The natural world includes both the physical world and the realm of conscious‑ ness, mental processes and ideas. Reflecting Moller and Wildwood, Warren suggests that the experience of encountering the 'transcendent' or feeling a deep connection to God could simply be another step

This section suggested multiple avenues for future development in non-theist thought, in terms of both the creation of a uniquely Quaker non-theist a/theology and dialogue with Quaker theists (including Christian theists). Dudiak's suggestion that theism and non-theism have a common path forward within Liberal Quakerism framed this discussion, demonstrating that both theists and non-theists have

the potential to gain from engagement with each other. Warren presents a vision for engagement which places the concerns of non-theists as a priority in the encounter, while Amoss presents the vision most concerned with seeking an equal space within Quakerism for the concerns and perspectives of both theists and non-theists.

6] Conclusion

This chapter has proposed future avenues for non-theism to grow: its self-definition, historiography and approach to history; interpretations of Quaker identity which engage in critical readings of a non‑theistic Quaker imaginary; and the engagement of both non-theism and theism as equal partners in the development of Liberal Quaker theology. Non-theism is a complex umbrella term encapsulating multiple spectra: the value of theistic constructions within Liberal Quakerism, the role of belief in the definition of non-theist identity and meaning, and the capacity of non-theism to craft its own theological thought.

Non-theism has not only already made contributions to the development of Liberal Quaker theology, especially in the role it played in the development of Universalist Quakerism, but it also has the potential for building bridges with Christocentric Liberal Quakerism in terms of a common theological language and imaginary. Moving forward, however, non-theism can only continue to make effective contributions to the development of Liberal Quakerism if it remains in dialogue with both Universalist and Christian Liberal Quakerism; following voices rejecting the value of theism will divorce non-theism from the rich theological history of Liberal Quakerism and imperil future development of non-theism within Liberal Quakerism.

- Amoss, George. The Postmodern Quaker, https://postmodernquaker.wordpress.com/

- Boulton, David (ed.). (2006). Godless for God's Sake: Nontheism in Contemporary Quakerism, Dent: Dales Historical Monographs.

- Cresson, 0. (2014). Quaker and Naturalist Too, Iowa City: Morning Walk Press. Website of Nontheist Friends, www.nontheistfriends.org/