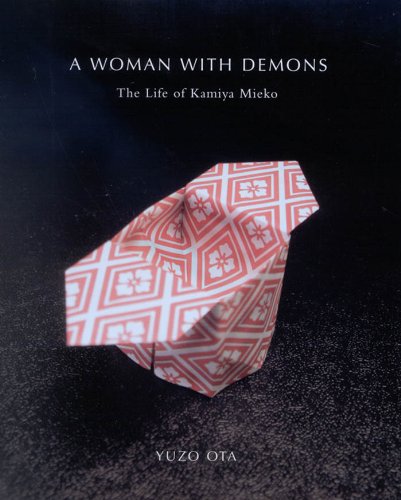

A Woman with Demons: The Life of Kamiya Mieko eBook : Ota, Yuzo: Amazon.com.au: Kindle Store

Yūzō ŌtaYūzō Ōta

A Woman with Demons: The Life of Kamiya Mieko Annotated Edition, Kindle Edition

by Yuzo Ota (Author) Format: Kindle Edition

Few English biographies about Japanese subjects provide such an intimate look into the subject's inner life.

Kamiya Mieko, the Japanese writer, psychiatrist, professor, and mystic, was a far more complex and intriguing figure than her popular image as a philanthropic doctor for leprosy patients suggests. A Woman with Demons corrects the myths about Kamiya's life through a close reading of her major work, What Makes Our Life Worth Living (1966), her other publications and her unpublished writings in four languages. In the first biography of Kamiya in English, Yuzo Ota focuses on her journey of self-discovery and her struggle to recover from the loss of a sense of meaning in life caused by the death of her first love. Ota explores how this traumatic event led to her identification with leprosy patients and created her desire to work for them.

Author / Editor information

Ota Yuzo :

Yuzo Ota is professor of history, McGill University, and the author of numerous books including

Basil Hall Chamberlain: Portrait of a Japanologist.

Topics

General Interest

Table of contents

Contents

Publicly Available v

Acknowledgments

Publicly Available vii

A Note on Names and Documentation

Publicly Available ix

Introduction

==

Introduction

Kamiya Mieko,1 whose life spanned the period between and , is remembered in Japan for her work in several different fields. Among other things, she was a doctor who treated psychiatric patients among leprosy victims; an author of books, such as Ikigai ni tsuite (What Makes Our Life Worth Living),2 dealing largely with existential questions; a translator from the original of Marcus Aurelius’s Meditations and some of Michel Foucault’s books; and a teacher who taught at several institutions in Japan, including Tsuda College, her alma mater, and left a lasting impression on her students.

In a letter written in , Kamiya told a friend that

What Makes Our Life Worth Living, published in , was then in its twenty-second edition.3 Most of her writings are still readily available. Her collected works in thirteen volumes published by the reputable Tokyo firm Misuzu Shobō between and 4 are still in print and continue to find many readers. Not only does she remain popular as an author but people of the highest intellectual calibre in Japan acknowledge her greatness. “She was a saint,”5 writes a leading intellectual of present-day Japan. Until a few years ago, however, despite the continued popularity of her writings, there were few studies of Kamiya Mieko. Now that is changing. Beginning in with Ejiri Mihoko’s biography, four books on Kamiya have been published in Japan in quick succession.6 She has also been the subject of a few television documentaries in the last few years, raising her profile even further in Japan.7

Kamiya, however, has no profile outside Japan. Having published two English-language articles in an international journal of psychiatry,8 she may be known to some specialists in the field outside Japan. But among the general public she is completely unknown. Even among Japan specialists, very few seem to know who she was. The biggest reason for this must be the language barrier. Although Kamiya had a remarkable knowledge of European languages, most of her publications with a few exceptions were in Japanese and the main stage of her activities after her student days was Japan. I believe that Kamiya deserves to be better known. To be sure, her intellectual achievement was severely curtailed by the fact that she was a housewife with relatively little free time during what were potentially her most creative years. But this only makes her life story more dramatic and interesting. Her life was in some ways as remarkable as that of Simone Weil (–) with whom she had certain traits in common – an interest in Plato and other classical Greek authors, a wide-ranging intellectual embrace of natural sciences and humanities, strong identification with human suffering, mysticism, a passionate love of music, especially that of Bach – though they were very different in other respects.9

In this biography, I hope to present Kamiya and her life in a way that is substantially different from other interpretations. To begin with, I would like to avoid hagiography. Kamiya’s life was a beautiful one, but I do not think that it was internally simple. Kamiya herself was keenly aware of the complexity of her personality with its many contradictory impulses. “A person possessed with seven demons – that truly is me,”10 she once wrote in her posthumously published diary. And later: “No matter whom I meet, I have an uneasy sense as if I were deliberately hiding something of my life from that person. That is because I behave as an ordinary housewife or, at most, only as ‘a housewife with a linguistic talent.’ What a complex, terrifying [osoroshii] person I am really. Very few people know this, however.”11 Previous biographers of Kamiya have not done justice to this remarkable complexity.

Kamiya’s life has usually been told with a focus on what appeared to be her philanthropic side. Thus, the realization of her youthful desire to work for leprosy patients despite the many obstacles she had to overcome – among them opposition from her father and her illnesses, including tuberculosis and cancer – was selected as the centrepiece of her life story. Clearly, this was a very important part of her life. But apart from the question of her real motive in working with leprosy patients (I will deal with this question later), I wonder whether it was the main plot. I wonder whether the central theme of her life was not rather her groping towards the discovery and fulfilment of her real mission in life as a writer. A friend once remarked to Kamiya, “You must be at a loss what to do when you get up in the morning, so many things you would like to do, and could do well.”12 As Kamiya was talented in so many ways, her search for her real mission lasted a very long time.

In the notebook that I call Toba Mitsuko Notebook after the pen name a youthful Kamiya wrote on the cover and in which she listed largely autobiographical topics for her future writings, she says in the entry for

January ,

I must not die before writing on the topics listed in this notebook. Even to the detriment of all other works, I should not fail to write on these topics. For, only this is what is unique to me. Other people besides myself can engage in medical research and practice. Obviously, other people can also teach languages and do translation. Other people can also replace me in the work of helping N [Kamiya Noburō, her husband] in his research (though the true significance of my helping him, of course, lies elsewhere). Other people can also discharge the duties of a mother besides me. However, nobody else has a personality structure like mine, has had experiences like mine, and has felt and thought as I have. To give expression to them in writing can be done by nobody else but me. Oh, God, if this is truly my mission, please give me the will and power to accomplish it. Please keep me alive until I complete this work.

By the time she wrote these words in January , she had come to feel that to leave behind her writings that expressed what she felt and thought was more important than anything else.

Kamiya’s conviction that her true mission lay in writing remained with her to the end of her life. She often reiterated the intention and prayer that she had committed to her diary in January . In the same notebook, for example, on July , she wrote: “As I prepare statistical tables for my dissertation, I again, in fact many many times, repeat the vow mentioned above from the very bottom of my heart.” The vow, of course, was the vow to complete her writings on the topics listed in the notebook before her death. Although circumstances prevented her from engaging in literary work in earnest until quite late in her life, she finally managed to publish What Makes Our Life Worth Living in . It was her first book, if we disregard her translations, and it was a major step towards fulfilling her mission. Almost to the last moment of her life, she strove to give expression to her intensely lived experiences and thoughts. The final part of the manuscript of Kamiya’s autobiography Henreki (Wanderings) was not sent to the Misuzu Shobō, her publisher, until October , a week before her death.13 By completing the autobiography, however, Kamiya seems to have fulfilled her vow more or less.14

Another area in which I would like to offer a new insight concerns the motivation for Kamiya’s work with leprosy patients. Many people interpreted this as a sheer philanthropy on her part. In their view Kamiya was a fortunate and gifted person from a good family whose life left little to be desired and who was struck by the misery of people far less fortunate than herself – somewhat like Albert Schweitzer, who had started working with people afflicted with disease, including lepers, in the Congo before she was born. Against this view – that it was out of compassion or pity that she decided to work for leprosy patients – I would like to suggest, following Mr Tsurumi Shunsuke,15 that Kamiya had been in despair about her life around the time she conceived the idea of working with leprosy patients, due to the death of a young man whom she loved. In my view, the farreaching and long-lasting impact of this loss upon Kamiya is a crucial key to understanding her life.

In fact, Kamiya’s most important work, What Makes Our Life Worth Living, cannot be understood properly unless one realizes that the author had once lost sight of what made her life worth living. In chapter , titled “What Destroys Our Sense That Life is Worth Living,” Kamiya quotes from “the writing of a girl who lost through death the young man with whom she had intended to share the future”: “With a sudden, tremendous bang, the earth around my feet collapsed and the heavy sky fell into it.

Unwittingly I covered my face with my hands and helplessly crouched in the middle of a road. I had a sensation of an endless fall into a dark abyss. He is gone, and with that I have lost the life which I had been living until his death. My life will never never return to what it had been. From now on, how and for what can I live?”16

This girl was Kamiya herself, although she never avowed it openly. The young man named Nomura Kazuhiko whom Kamiya loved died on January , and she learned of his death the following day. Thus in her shuki (see the note on names and documentation, above) for January , she writes: “The sensation, which I had five years ago today, that both the heaven and the earth were collapsing, has recurred many times today to wring my heart.” And again on January : “The sensation as if everything collapses which I had when I learned of his death – it is like my life itself.”

The knowledge of the crushing impact that Nomura Kazuhiko’s death had upon Kamiya enables us to see What Makes Our Life Worth Living as an intensely personal book despite the surface appearance of scholarly detachment and objectivity created by the long list of books and articles Kamiya cited and the absence of overt references to her own experience.

In chapter , “Discovery of a New Meaning of Life,” Kamiya discusses various processes by which a lost sense of meaning in life can be replaced. One of the processes she mentions is “henkei” (transformation) and she writes as follows: “The most common type of transformation is transformation of love towards a particular person into love towards a larger number of people.” Then she quotes the following lines from “Shunjitsu kyōsō” (“Crazy Thoughts on a Spring Day”) of Nakahara Chūya (– ), one of the most important Japanese poets of the twentieth century:

Because your loved one died,

Because that person is really dead,

Because nothing can alter that fact,

For the sake of that person, for the sake of that person,

You must decide to serve others,

You must decide to serve others.17

Kamiya must have felt as if the poet was talking about her; her desire to serve leprosy patients was born in the spring of only a few months after Nomura Kazuhiko’s death, as we shall see in chapter . The preceding lines of the poem, which Kamiya did not quote, must have struck her even more as an expression of her own feeling.

When your loved one died, You must commit suicide.

When your loved one died,

There is no other way out but that.

However, if your karma (?) [sic] is too bad

And if you find yourself still alive, You must decide to serve others.

You must decide to serve others.

That Kamiya was often tempted by the idea of suicide after the death of Nomura Kazuhiko is reflected in her poem “A Haunted Pool” (“Ma no fuchi”),18 dated April , less than three months after the death of Nomura Kazuhiko. The story told by this poem is as follows: the narrator “I” is tempted by a voice coming from the deep pool near her school to drown herself. The idea of death is quite tempting to her with her “broken heart” but the spell cast by the voice is broken by the school bell and she runs back to school without committing suicide. Her suicidal inclination after Nomura Kazuhiko’s death is overtly expressed in her letter of December 19 to his parents, Nomura Kodō, a famous popular writer and music critic, and Nomura Hana: “Let me thank you most heartily once again for all your love which you have shown towards me. It is entirely thanks to you both that I have managed to refrain from committing suicide.”

Kamiya’s life was characterized by her long struggle to recover from the loss of Nomura Kazuhiko and to make some sense of that loss. However, this crucial aspect of her life has been virtually ignored – not deliberately but because in those of her writings that have been published so far, Kamiya never mentions the loss of Nomura Kazuhiko directly. The few allusions to his death are too oblique to be recognized. Probably the least oblique among them is the following passage, which Kamiya wrote more than twenty-five years after his death: “I had to confront Death quite early. I collided with it headlong. Death came as my destiny, as something which stood in front of me blocking my way. That shock was too fatal. After that, other deaths, even the death of persons closest to me, in comparison, could no longer rouse within me emotions of the same intensity. It was perhaps a kind of immunity. I have come to live as if I were always looking at Death face to face.”20 This published passage, which numerous people must have read, points to Kamiya’s own understanding of her life as one that in a sense began with a terrible loss that had a lasting effect upon her. This isolated passage, however, was not enough to call people’s attention to the importance of this early loss and so far nobody except myself has tried to interpret her life in that light.21

The absence of overt references in Kamiya’s published works to the death of Nomura Kazuhiko or to her relationship with him should not be attributed to a desire to keep these events secret. From the topics listed in the Toba Mitsuko Notebook we know that Kamiya had intended to deal with her relationship with him in a few works, especially one entitled “Hatsushimo” (“First Frost”). That she did not mean to guard her relationship with Kazuhiko as a secret can be seen from the following quotation from her shuki of December :

When we come to think of it, a fairly large number of writers, especially Tōson [Shimazaki Tōson –, a writer whom Kamiya regarded very highly], used their own personal materials for their writings to the extent that we might be justified to say that they wrote autobiographic works from the beginning to the end. Accordingly, there is no reason for me to hesitate to write on my own experiences. What matters is to produce a work which penetrates to the essence of things through my own experiences. As I gained this conviction, I started writing “Hatsushimo.”

Kamiya Mieko’s collected works in thirteen volumes is a considerable achievement judged by ordinary standards. However, Kamiya, one of the most remarkable women of twentieth-century Japan, is not really a person to be judged by ordinary standards. What she actually achieved as an author may appear to be relatively meagre considering her extraordinary talent. In my opinion, the most interesting volume of all is The Diary of Younger Days (Wakaki hi no nikki), which prints a large proportion of her diary from the middle of April to the end of . Kamiya kept her diary without any thought of publishing it in future. If we remember that two more volumes of her collected works are devoted to her diary and correspondence, the quantity of her writings for publication seems relatively modest. ualitatively as well, they do not quite come up to the standards that one would expect of a person of such dazzling talents as revealed in her Diary of Younger Days. The discrepancy between Kamiya’s early promise and her actual achievement is related to the fact that in the Japan of her time a woman could not fulfil an intellectual vocation as easily as her male counterpart, especially if she decided to marry. Household chores were shouldered almost exclusively by women, and there were not yet washing machines and other electric appliances to lighten the burden of housework. Even when Kamiya was an unmarried woman with far more free time than she had after her marriage, she was painfully aware of the disadvantage of being a woman with intellectual aspirations, as she wrote in her diary: “Life demands a huge price from a woman – almost her entire existence – in the form of everyday life. Even in my present mode of life, I have to spend a much greater amount of time and energy than a man for the sake of everyday life – not in an abstract manner as is the case with a man but in a really concrete, urgent manner to provide daily food and clothes for the household.”22

After her marriage, the obstacles to fulfilment of her intellectual vocation multiplied many times, especially since Kamiya wholeheartedly wanted to be a good wife and mother. The perceived discrepancy between her promise and her achievement may be one reason why her death at the age of sixty-five was thought by some to have been premature.23 In my view, however, if we take into account not only her writings but also her life as a whole, the impression of a premature death vanishes. Her life with all the possibilities that remained largely unrealized until the end would appear like a beautiful work of art worthy of our admiration and contemplation.

In this book I shall try to convey my understanding of Kamiya Mieko and her life as a whole. However, I concentrate heavily on the period before her marriage, which occurred in , roughly in the middle of her life. I devote only two short chapters to the second half of her life after marriage. Since many of Kamiya’s close relatives and friends are alive, I have to balance the demand, imposed upon me as her biographer, to draw her portrait as truthfully as possible, with the need to protect the privacy of people, especially her close relatives, who figure in the unpublished part of the Kamiya Mieko Papers, which I was allowed to examine. As a pragmatic solution, I decided to make Kamiya’s marriage in the dividing line. For the period before that, I have used pertinent unpublished materials from the Kamiya Mieko Papers to narrate the story of her life. For the periods after her marriage, I have refrained from quoting directly from any of Kamiya Mieko’s unpublished writings with the exception of a few quotations that contain nothing that might infringe upon the privacy of other people. I have tried to reconstruct her life path almost exclusively on the basis of the materials already published in her collected works. This method naturally diminishes the value of this book as a regular biography. However, to write a regular biography of Kamiya Mieko was not necessarily my aim. My main interest has been to elucidate the history of her inner rather than her external life. I hope that the reader will get a clear impression of this remarkable Japanese woman from my book.

==

Publicly Available xi

The Child of Very Different Parents: Family Background and Early Childhood, 1914–1923

===

Requires Authentication 3

Birth of a Little Cosmopolitan: The Swiss Days, 1923–1926

Requires Authentication 17

“La jeunesse riche et vivante”: Readjustment to Japan and Student Life at Seijō Higher Girls' School and Tsuda College

Requires Authentication 38

Love with Nomura Kazuhiko and the Lasting Impact of His Death

Requires Authentication 51

Progress towards the Affirmation of Life: The American Days, 1938–1940

Requires Authentication 84

A Medical Student in Japan, 1941–1944

Requires Authentication 129

An Unmarried Female Psychiatrist at Tokyo University Hospital, 1944–1946

Requires Authentication 166

Kamiya Mieko in her Later Years

Requires Authentication 204

By Way of a Conclusion: A Happy Ending

Requires Authentication 217

Notes

Requires Authentication 223

Index

Requires Authentication 253

Bibliographic data

Bibliographic data

Publishing information

Pages and Images/Illustrations in book

eBook published on:

February 22, 2006

eBook ISBN:

9780773559981

Main content:

288

==

A Woman With Demons: The Life of Kamiya Mieko (1914-1979) (review)

Janice Matsumura

Bulletin of the History of Medicine

Volume 82, Number 1, Spring 2008

Yuzo Ota . A Woman With Demons: The Life of Kamiya Mieko (1914-1979). Montreal: McGill-Queen's University Press, 2006. xxiv + 261 pp.

The subject of television documentaries and at least four biographies since the 1990s, Kamiya Mieko continues to win admirers in Japan as a homegrown version of Albert Schweitzer. As a psychiatrist—a member of a profession that in Japan received less government support than did medical specialties dealing with infectious diseases—she drew attention to the psychological dimension of somatic disorders by examining the impact of social isolation on leprosy patients. Gaining renown as the author of a 1966 existential treatise, What Makes Our Life Worth Living (Ikigai ni tsuite), she helped to increase public sympathy for individuals suffering from stigmatizing ailments.

In this first English-language study of Kamiya, Yuzo Ota nevertheless criticizes the hagiographic quality of earlier accounts that focus on the obstacles that Kamiya had to overcome, such as family opposition and struggles with tuberculosis and cancer, in order to devote herself to leprosy patients. Through an examination of unpublished material preserved by Kamiya's husband and a rereading of her published works, Ota demonstrates how such views cover up the complexity of her personality. Rejecting the saintly image that others imposed on her, she described herself as a "person possessed with seven demons" whose "complex, terrifying [osoroshii]" qualities were undetected by the majority of people who knew her (p. xiii).

Ota delves into Kamiya's family background, discussing the marital discord between her parents, and notes how Kamiya, as a psychiatrist, later concluded that she had inherited both parents' conflicting extrovert and introvert characters. The daughter of a diplomat posted in Switzerland, she attended an elementary school headed by the psychologist Jean Piaget. As the eldest daughter, she cared for her siblings when her mother remained abroad and began reading works on child psychology in order to fulfill this responsibility.

According to Ota, the death of her first love, Nomura Kazuhiko, in 1934 marked the turning point in Kamiya's life, propelling her into a long-lasting search for personal meaning and sparking her interest in working in leprosaria. However, he overturns the view that she was unwavering in her commitment to such work by revealing her doubts about pursuing a medical career. Moreover, he shows how a desire to understand herself better led her to specialize instead in psychiatry, the study of which led her to believe that she was not a "normal" person. It was only after her marriage in 1946 that Kamiya began to seriously examine conditions among leprosy patients.

Ota devotes only the last two short chapters to the post-1946 period, the time when Kamiya became more productive as a psychiatrist. He explains that this focus was determined by his respect for the privacy of relatives and friends who are still alive, and also by his wish to produce, not a "regular" biography of Kamiya, but "the history of her inner rather than her external life" (pp. xxiii–xxiv). However, in order to assess his subject's inner feelings, he occasionally has to rely on the products of her external life, her medical writings of the 1960s. For example, he [End Page 236] uses a psychological assessment of a leprosy patient that Kamiya made decades later to establish a case for her sense of identification with such individuals in the period immediately following Nomura's death in 1934. While one wishes that Ota had extended his analysis to include more of Kamiya's psychiatric studies, a subject more appealing to historians of medicine, his book should attract the attention of those interested in the topic of female professionals in Japan, and it may become a launching pad for future examinations of Kamiya.

Janice Matsumura

Simon Fraser University

Copyright © 2008 The Johns Hopkins University Press

...

==